✊ SPECIAL NAKBA _ Why My Father Made Me Forget Our Palestinian Catastrophe

Seraj

Assi, The Atlantic, May 15, 2018

How does

a boy growing up in Israel remember how many of his people lost their homes in

1948, if no one will teach him?

a boy growing up in Israel remember how many of his people lost their homes in

1948, if no one will teach him?

|

|

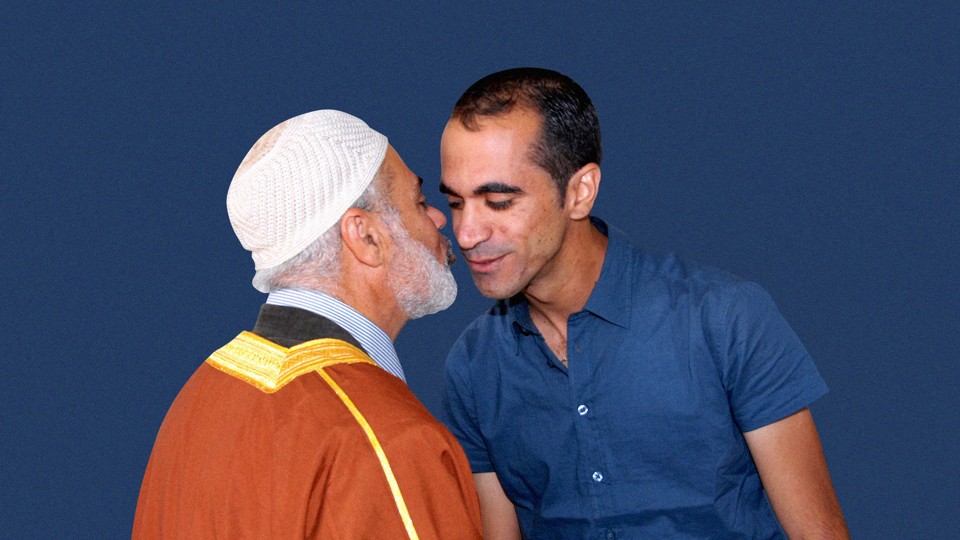

Seraj

Assi and his father Seraj Assi / The Atlantic |

When the

creation of the State of Israel 70 years ago led to a mass Palestinian exodus, only

about 150,000 Palestinians out of nearly

1 million who had lived on the territory managed to remain within

the new state. Among them were my grandparents. And yet, it wasn’t until I was

20 years old that I first heard of the nakba, an Arabic term meaning

“catastrophe” that many Palestinians use to mark the events of 1948.

Ironically,

I heard the word from a Jewish friend at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. In

my excitement, I called my father and told him about my thrilling new

discovery. He faltered, then advised me to get this nakba out of my system.

I heard the word from a Jewish friend at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. In

my excitement, I called my father and told him about my thrilling new

discovery. He faltered, then advised me to get this nakba out of my system.

I hung up

and stood there dumbly, wondering at the way my father seemed to be shunning

the truth of his own existence. For 20 years, he had managed to silence,

suppress, and obliterate the mention of the very word that binds Palestinians

together in a shared memory.

and stood there dumbly, wondering at the way my father seemed to be shunning

the truth of his own existence. For 20 years, he had managed to silence,

suppress, and obliterate the mention of the very word that binds Palestinians

together in a shared memory.

But I

could hardly blame him. Between 1948 and 1966, men like my father and

grandfather were forced to live under a military regime imposed by Israel on

its remaining Arab population. Their freedom of movement was controlled by

Israeli permit requirements and curfews. They were restricted from seeing their

fellow Palestinians and Arabs in neighboring countries like Jordan and Egypt,

in the West Bank and Gaza, and even in other towns and villages inside Israel.

Haunted by the fresh memory of loss and displacement, the first generation of

Arabs in Israel was born into national limbo. Virtually overnight, they became

strangers in their own homeland.

could hardly blame him. Between 1948 and 1966, men like my father and

grandfather were forced to live under a military regime imposed by Israel on

its remaining Arab population. Their freedom of movement was controlled by

Israeli permit requirements and curfews. They were restricted from seeing their

fellow Palestinians and Arabs in neighboring countries like Jordan and Egypt,

in the West Bank and Gaza, and even in other towns and villages inside Israel.

Haunted by the fresh memory of loss and displacement, the first generation of

Arabs in Israel was born into national limbo. Virtually overnight, they became

strangers in their own homeland.

To my

father, the nakba never truly ended. But whether out of fear or brutal realism,

he refused to bequeath it to his son. He believed that third-generation Arabs

in Israel could survive only through ignorance of what had come before. This

was his mantra, one I heard repeated by him and other Palestinians of his

generation.

father, the nakba never truly ended. But whether out of fear or brutal realism,

he refused to bequeath it to his son. He believed that third-generation Arabs

in Israel could survive only through ignorance of what had come before. This

was his mantra, one I heard repeated by him and other Palestinians of his

generation.

As a

youth I was educated in Arab schools in a small village near Jaffa, where I

tried to make sense of the internal chaos my history teachers bred in my mind.

The word nakba was omitted from Arabic textbooks, not to mention Hebrew

textbooks. My teachers never dared mention it. I recall Jewish officials coming

to our school around Independence Day—in retrospect, they may have been trying

to monitor for use of the n-word, though if that was the goal it was an absurd

effort. At the time the students there had no idea that such a word even

existed. If anything, we thought that nakba was Arabic for the Holocaust.

youth I was educated in Arab schools in a small village near Jaffa, where I

tried to make sense of the internal chaos my history teachers bred in my mind.

The word nakba was omitted from Arabic textbooks, not to mention Hebrew

textbooks. My teachers never dared mention it. I recall Jewish officials coming

to our school around Independence Day—in retrospect, they may have been trying

to monitor for use of the n-word, though if that was the goal it was an absurd

effort. At the time the students there had no idea that such a word even

existed. If anything, we thought that nakba was Arabic for the Holocaust.

The word

“Palestine” and its derivations were equally absent. The history of Arab

Palestine that had vanished in 1948 was passed over in silence among families

like mine in Israel. The dream of a future Palestinian nationhood also went

undiscussed within our schools and homes. We saw no such thing as a Palestinian

people. Palestinians across the border were “West Bankers” and “Gazans” but

never Palestinians; they, not the Israelis, were our “other.” We, the

Palestinians within Israel, were simply “Arabs”—neither Israeli nor Palestinian,

but a nebulous species devoid of national character, identity, and memory.

“Palestine” and its derivations were equally absent. The history of Arab

Palestine that had vanished in 1948 was passed over in silence among families

like mine in Israel. The dream of a future Palestinian nationhood also went

undiscussed within our schools and homes. We saw no such thing as a Palestinian

people. Palestinians across the border were “West Bankers” and “Gazans” but

never Palestinians; they, not the Israelis, were our “other.” We, the

Palestinians within Israel, were simply “Arabs”—neither Israeli nor Palestinian,

but a nebulous species devoid of national character, identity, and memory.

Meanwhile,

I was overfed with lectures about Israel’s independence, Zionist pioneers and

peace doves, and the “Promised Land.” Israeli national myths—for instance, that

Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land”—masqueraded

as historical facts. Decorating the classroom walls were modern maps that

labeled the West Bank as “Judea and Samaria,” a biblical designation used by

Israelis who support the settlement enterprise. Zionist mantras, ranging from

“God promised the land to the Jews” to “The Zionists made the desert bloom,”

were repeated over and over, and Zionist platitudes were engraved deep in my

Arab mind, even if some seemed mutually contradictory: “The Arabs fled because

they were cowards.” “The Arabs attacked Israel first.” “Palestine was an empty

land before the Zionists.” “Israelis have lived in the Land of Israel for 3,000

years.”

I was overfed with lectures about Israel’s independence, Zionist pioneers and

peace doves, and the “Promised Land.” Israeli national myths—for instance, that

Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land”—masqueraded

as historical facts. Decorating the classroom walls were modern maps that

labeled the West Bank as “Judea and Samaria,” a biblical designation used by

Israelis who support the settlement enterprise. Zionist mantras, ranging from

“God promised the land to the Jews” to “The Zionists made the desert bloom,”

were repeated over and over, and Zionist platitudes were engraved deep in my

Arab mind, even if some seemed mutually contradictory: “The Arabs fled because

they were cowards.” “The Arabs attacked Israel first.” “Palestine was an empty

land before the Zionists.” “Israelis have lived in the Land of Israel for 3,000

years.”

Indeed, I

believed that Israel had existed in Palestine from time immemorial. I remember

asking my history teacher, “From whom did Israel gain independence in 1948?” He

hummed, gazed out into the distance, and said nothing. I gathered from his

silence that Israel was a biblical miracle, somehow both eternal and created,

like a national “big bang.”

believed that Israel had existed in Palestine from time immemorial. I remember

asking my history teacher, “From whom did Israel gain independence in 1948?” He

hummed, gazed out into the distance, and said nothing. I gathered from his

silence that Israel was a biblical miracle, somehow both eternal and created,

like a national “big bang.”

I vividly

recall those Independence Day moments when we Arab kids were herded into the

schoolyard and ordered to stand still in memory of fallen Israeli soldiers. A

long, torturous minute would pass before the siren died out and we burst into

celebration, surrounded by fluttering Israeli flags and the melody of Hatikva,

the Israeli national anthem. It’s no wonder Arabs in Israel continue to call

Israel’s Independence Day “Independence Holiday.”

recall those Independence Day moments when we Arab kids were herded into the

schoolyard and ordered to stand still in memory of fallen Israeli soldiers. A

long, torturous minute would pass before the siren died out and we burst into

celebration, surrounded by fluttering Israeli flags and the melody of Hatikva,

the Israeli national anthem. It’s no wonder Arabs in Israel continue to call

Israel’s Independence Day “Independence Holiday.”

In the

end, it is not what I learned, but what I did not learn, that has most

profoundly shaped my memory: I did not learn, for instance, what drove

thousands of people to abandon their homes and flee for their lives—leaving

behind warm beds and brewed coffee, damp laundry still hanging from their

windows, millstones running at their doorsteps—never to return. There were no

answers, only clues wrapped in decades of collective fear and repression.

end, it is not what I learned, but what I did not learn, that has most

profoundly shaped my memory: I did not learn, for instance, what drove

thousands of people to abandon their homes and flee for their lives—leaving

behind warm beds and brewed coffee, damp laundry still hanging from their

windows, millstones running at their doorsteps—never to return. There were no

answers, only clues wrapped in decades of collective fear and repression.

Today, I

find it miraculous that I have lived and endured a life in Israel where, for

much of it, nearly everybody was pretending that there had never been any nakba.

For some Israeli Jews, the nakba never happened—or if it did, it happened

because it had to happen. For some Arabs of my father’s and grandfather’s

generations, the nakba must not happen again, even in remembrance.

find it miraculous that I have lived and endured a life in Israel where, for

much of it, nearly everybody was pretending that there had never been any nakba.

For some Israeli Jews, the nakba never happened—or if it did, it happened

because it had to happen. For some Arabs of my father’s and grandfather’s

generations, the nakba must not happen again, even in remembrance.

But for

young Palestinians of my generation, the nakba happened and happens still. Some

of us feel as if our elders were enlisted to help hide the truth, and we frown

sternly on their complicity in breeding a collective amnesia. Yet we also

realize that for our fathers and grandfathers in Israel, keeping quiet about it

was a survival tactic: The erasure bolstered their endurance. The irony is that

those who lived the real nakba are still less inclined to invoke it than those

who, like myself, are living it symbolically and from afar.

young Palestinians of my generation, the nakba happened and happens still. Some

of us feel as if our elders were enlisted to help hide the truth, and we frown

sternly on their complicity in breeding a collective amnesia. Yet we also

realize that for our fathers and grandfathers in Israel, keeping quiet about it

was a survival tactic: The erasure bolstered their endurance. The irony is that

those who lived the real nakba are still less inclined to invoke it than those

who, like myself, are living it symbolically and from afar.

Israel

has never officially accepted responsibility for the nakba, let alone taught it

as part of its history. In 2011, Israel went so far as to pass the “Nakba Law,”

which authorizes the finance minister to reduce state funding for institutions

that mark Israel’s Independence Day as a day of mourning. This law restricts

the ability of Palestinians to publicly commemorate a tragic past.

has never officially accepted responsibility for the nakba, let alone taught it

as part of its history. In 2011, Israel went so far as to pass the “Nakba Law,”

which authorizes the finance minister to reduce state funding for institutions

that mark Israel’s Independence Day as a day of mourning. This law restricts

the ability of Palestinians to publicly commemorate a tragic past.

Israel

seems to be under the perilous illusion that it can write off the national

aspirations of millions of Palestinians by simply rewriting history. But

history flows like a river out of the past into the present. As a Palestinian

Arab who was born and raised in Israel, and who has inherited the double shock

of catastrophe and independence, defeat and victory, erasure and memory, I feel

like I am standing in the middle of a bridge where I can see both banks of the

river. Perhaps one day Israelis too will walk that shaky bridge and see what

lies on the other bank.

seems to be under the perilous illusion that it can write off the national

aspirations of millions of Palestinians by simply rewriting history. But

history flows like a river out of the past into the present. As a Palestinian

Arab who was born and raised in Israel, and who has inherited the double shock

of catastrophe and independence, defeat and victory, erasure and memory, I feel

like I am standing in the middle of a bridge where I can see both banks of the

river. Perhaps one day Israelis too will walk that shaky bridge and see what

lies on the other bank.