The miracle of water

August 1, 2016

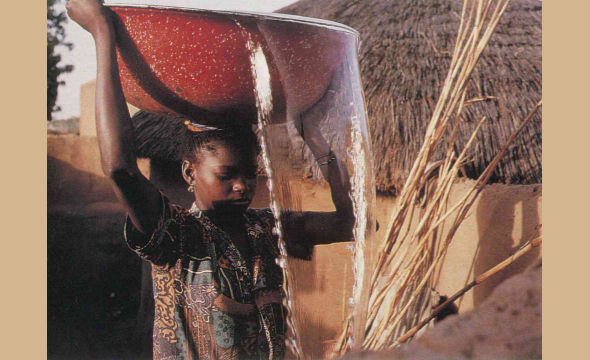

Photo from ‘Inside an African Village: Heart and soul – ten years of change’, New Internationalist magazine, June 1995 (Issue 268). by Chris Brazier

New Internationalist editor Chris Brazier returns to Burkina Faso every decade to produce a magazine on the African country. He has produced three issues and is currently researching his fourth. Read parts one, two or three of this blog series. Part four is below.

One of the most salutary lessons I have always learned from being in the village Sabtenga is to value water as the greatest of gifts rather than to take it for granted as we inevitably do at home.

That first stay here in 1985, when the rains were chronically late and the ground was cracked and parched as I have never seen it since, it would have been impossible to take any of the water we used for granted. I knew then that every drop I used, whether for drinking or for washing, had been carried for more than a mile from the well in huge metal bowls on the heads of the local girls and women. So heavy was one of these metal bowls that I could barely lift it up to head level, let alone balance it there and walk, though I did once try, to the great and understandable amusement of the group of girls watching.

When I returned to England that first year I felt like I would never again fail to appreciate what a miracle it was that we could turn on a tap and run water aplenty for ourselves at will. But such is human nature that it is difficult to retain such a clear sense when the water runs so abundantly at the flick of a wrist – and when you know you can trust its healthy properties so absolutely. The weeks and months pass and you slip back into ready, unthinking acceptance instead of appreciating your good fortune at having been born into a place where water is – for the moment at least – not one of life’s problems.

In 1995 New Internationalist editor Chris Brazier returned to Burkina Faso, 10 years after his first trip (described in this blog) to see how people’s lives had changed.

Each subsequent visit has reunited me, however, with this sense of water’s preciousness. Things have changed for the better over the years. By 2005 new pumps had been installed closer to the concessions (the French name for the walled compounds containing a family’s houses) and the children would collect it in plastic containers, often carrying it on a donkey cart rather than on their heads. Yet now I find that in the subsequent 11 years the water table has fallen much lower in the dry season, meaning that new, much deeper pumps have had to be sunk that can access the deep reserves all the year round. These pumps are much more expensive to sink and there are only a few so far. I will write more about this problem in the January/February issue of the magazine.

My own access to water while here is also less problematic. In 2005 I was living in the town of Garango and would go out with a bucket along with other residents to fetch water from a standpipe in the street. Here, in Garango again, but in a compound owned by the NGO Association Dakupa, I can walk out of my bedroom and fill a bucket from a standpipe in the yard not ten metres away. But still there is an acute sense of water’s value that derives from having fetched it in a bucket rather than having it run from a tap. I know full well that I will fall again into the habit of taking for granted that I have tap water to drink and a shower in the morning once I am at home. But at least these weeks in Burkina Faso reunite me for a period with an awareness of how fortunate we are in the Global North in this respect – and how difficult access to water remains for people in other parts of the world.