Gaza now has a toxic ‘biosphere of war’ that no one can escape

Mark

Zeitoun & Ghassan Abu Sitta, The Conversation, 27 avril 2018

Gaza has

often been invaded for its water. Every army leaving or entering the Sinai

desert, whether Babylonians, Alexander the Great, the Ottomans, or the British,

has sought relief there. But today the water of Gaza highlights a toxic

situation that is spiralling out of control.

often been invaded for its water. Every army leaving or entering the Sinai

desert, whether Babylonians, Alexander the Great, the Ottomans, or the British,

has sought relief there. But today the water of Gaza highlights a toxic

situation that is spiralling out of control.

|

|

Mohammed

Saber / EPA |

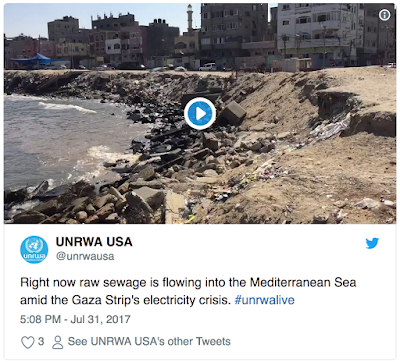

A

combination of repeated Israeli attacks and the sealing of its borders by

Israel and Egypt, have left the territory unable to process its water or waste.

Every drop of water swallowed in Gaza, like every toilet flushed or antibiotic

imbibed, returns to the environment in a degraded state.

When a

hospital toilet is flushed, for instance, it seeps untreated through the sand

into the aquifer. There it joins water laced with pesticides from farms, heavy

metals from industry, and salt from the ocean. It is then pumped back up by

municipal or private wells, joined with a small fraction of freshwater

purchased from Israel, and cycled back into people’s taps. This results in

widespread contamination and undrinkable

drinking water, about 90% of which exceeds the World Health

Organisation (WHO) guidelines for salinity and chloride.

hospital toilet is flushed, for instance, it seeps untreated through the sand

into the aquifer. There it joins water laced with pesticides from farms, heavy

metals from industry, and salt from the ocean. It is then pumped back up by

municipal or private wells, joined with a small fraction of freshwater

purchased from Israel, and cycled back into people’s taps. This results in

widespread contamination and undrinkable

drinking water, about 90% of which exceeds the World Health

Organisation (WHO) guidelines for salinity and chloride.

Incredibly,

conditions are getting worse, thanks to the emergence of “superbugs”. These

multi-drug resistant organisms have developed thanks to an over-prescription

of antibiotics by doctors desperate to treat the victims of the

seemingly endless assaults. The more injury there is, the more chance there is

of re-injury. Less regular access to clean water means infections

will spread faster, bugs will be stronger, more antibiotics will be

prescribed – and the victims will be ever-more weakened.

conditions are getting worse, thanks to the emergence of “superbugs”. These

multi-drug resistant organisms have developed thanks to an over-prescription

of antibiotics by doctors desperate to treat the victims of the

seemingly endless assaults. The more injury there is, the more chance there is

of re-injury. Less regular access to clean water means infections

will spread faster, bugs will be stronger, more antibiotics will be

prescribed – and the victims will be ever-more weakened.

|

| Filling up, at Khan Younis refugee camp in southern Gaza. Mohammed Saber / EPA |

The

result is what has been termed a toxic ecology or “biosphere of

war”, of which the noxious water cycle is just one part. A biosphere

refers to the interaction of all living things with the natural resources that

sustain them. The point is that sanctions, blockades and a permanent state of

war affects everything that humans might require in order to thrive, as water

becomes contaminated, air is polluted, soil loses its fertility and livestock succumb to

diseases. People in Gaza who may have evaded bombs or sniper fire

have no escape from the biosphere.

result is what has been termed a toxic ecology or “biosphere of

war”, of which the noxious water cycle is just one part. A biosphere

refers to the interaction of all living things with the natural resources that

sustain them. The point is that sanctions, blockades and a permanent state of

war affects everything that humans might require in order to thrive, as water

becomes contaminated, air is polluted, soil loses its fertility and livestock succumb to

diseases. People in Gaza who may have evaded bombs or sniper fire

have no escape from the biosphere.

War

surgeons, health anthropologists and water engineers – including ourselves –

have observed this situation developing wherever protracted

armed conflict or economic sanctions grind on, as with water systems

in Basrah

and health systems throughout

Iraq or Syria.

It’s now well past time to clean it up.

surgeons, health anthropologists and water engineers – including ourselves –

have observed this situation developing wherever protracted

armed conflict or economic sanctions grind on, as with water systems

in Basrah

and health systems throughout

Iraq or Syria.

It’s now well past time to clean it up.

There is

water – for some

water – for some

It’s not

as if there is no fresh water nearby to alleviate the situation in Gaza. Just a

few hundred metres from the border are Israeli farms that use freshwater pumped

from Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee) to grow herbs destined for European

supermarkets. As the lake is around 200km to the north and lies 200 metres

below sea level, a massive amount of energy is used to pump all that water. The

lake water is also fiercely contested by Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and

Palestinians in the West Bank, each of which is seeking their legal

entitlement of the Jordan River basin.

as if there is no fresh water nearby to alleviate the situation in Gaza. Just a

few hundred metres from the border are Israeli farms that use freshwater pumped

from Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee) to grow herbs destined for European

supermarkets. As the lake is around 200km to the north and lies 200 metres

below sea level, a massive amount of energy is used to pump all that water. The

lake water is also fiercely contested by Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and

Palestinians in the West Bank, each of which is seeking their legal

entitlement of the Jordan River basin.

|

|

Gaza City

on one side of the border, Israeli farms on the other. Google Maps |

Meanwhile,

Israel desalinates so much seawater these days that its municipalities are

turning it down. Excess desalinated water is being used to irrigate crops, and

the country’s water authority is even planning to use it to refill

Tiberias itself – a bizarre and irrational cycle, considering the

lake water continues to be pumped the other direction into the desert. There is

now so much manufactured water that some Israeli engineers can declare that

“today, no one in Israel experiences water scarcity”.

Israel desalinates so much seawater these days that its municipalities are

turning it down. Excess desalinated water is being used to irrigate crops, and

the country’s water authority is even planning to use it to refill

Tiberias itself – a bizarre and irrational cycle, considering the

lake water continues to be pumped the other direction into the desert. There is

now so much manufactured water that some Israeli engineers can declare that

“today, no one in Israel experiences water scarcity”.

But the

same cannot be said for Palestinians, especially not those in Gaza. People

there have resorted to various ingenious filters, boilers, or under-the-sink or

neighbourhood-level desalination units to treat their water. But these sources

are unregulated, often full of germs, and just another reason children are

prescribed antibiotics – thus continuing the pattern of injury and re-injury.

Doctors, nurses, and water maintenance crews meanwhile try to do the impossible

with the minimal medical equipment at their disposal.

same cannot be said for Palestinians, especially not those in Gaza. People

there have resorted to various ingenious filters, boilers, or under-the-sink or

neighbourhood-level desalination units to treat their water. But these sources

are unregulated, often full of germs, and just another reason children are

prescribed antibiotics – thus continuing the pattern of injury and re-injury.

Doctors, nurses, and water maintenance crews meanwhile try to do the impossible

with the minimal medical equipment at their disposal.

The

implications for all those who invest in Gaza’s repeatedly

destroyed water and health projects are clear. Providing more

ambulances or water tankers – the “truck and chuck” strategy – might work when

conflicts are at their most acute, but they are never more than a band aid.

Yes, things will get better in the short term, but soon enough Gaza will be

onto the next generation of antibiotics, and dealing with teflon-coated

superbugs.

implications for all those who invest in Gaza’s repeatedly

destroyed water and health projects are clear. Providing more

ambulances or water tankers – the “truck and chuck” strategy – might work when

conflicts are at their most acute, but they are never more than a band aid.

Yes, things will get better in the short term, but soon enough Gaza will be

onto the next generation of antibiotics, and dealing with teflon-coated

superbugs.

Donors

must instead design programmes suited to the all-pervasive and incessant

biosphere of war. This means training many more doctors and nurses, providing

more medicines, and infrastructure support for health and water services. More

importantly, donors should build-in political “cover” to protect their

investments (if not the local children), perhaps by calling for those who

destroy the infrastructure to foot the bill for repairs.

must instead design programmes suited to the all-pervasive and incessant

biosphere of war. This means training many more doctors and nurses, providing

more medicines, and infrastructure support for health and water services. More

importantly, donors should build-in political “cover” to protect their

investments (if not the local children), perhaps by calling for those who

destroy the infrastructure to foot the bill for repairs.

And there

is an even bigger message for the rest of us. Our research shows that war is

more than simply armies and geopolitics – it extends across entire ecosystems.

If the dehumanising ideology behind the conflict was confronted, and if excess

water was diverted to people rather than to lakes, then the easily avoidable

repeated injuries suffered by people in Gaza would become a thing of the past.

Palestinians would soon find their biosphere a whole lot healthier.

is an even bigger message for the rest of us. Our research shows that war is

more than simply armies and geopolitics – it extends across entire ecosystems.

If the dehumanising ideology behind the conflict was confronted, and if excess

water was diverted to people rather than to lakes, then the easily avoidable

repeated injuries suffered by people in Gaza would become a thing of the past.

Palestinians would soon find their biosphere a whole lot healthier.