🌐 WOMEN’S STORIES _ Romaine Brooks

By Miranda Bain,

The Heroine Collective

Artist

American

Artist Romaine Brooks moved among the wealthy, lesbian social circles

of 1920s Paris. Living in the world of Picasso and Matisse, Brooks has been

largely forgotten by mainstream culture. Yet, her contribution was an important

one. She was a complicated artist who defied convention both in terms of

her lesbianism, and in her radical artistic output which subverted the

male gaze in an almost pre-modern figurative style.

Artist Romaine Brooks moved among the wealthy, lesbian social circles

of 1920s Paris. Living in the world of Picasso and Matisse, Brooks has been

largely forgotten by mainstream culture. Yet, her contribution was an important

one. She was a complicated artist who defied convention both in terms of

her lesbianism, and in her radical artistic output which subverted the

male gaze in an almost pre-modern figurative style.

I grasped

every occasion no matter how small, to assert my independence of views

Born in

1874, Brooks had an unhappy childhood, plagued by physical and emotional abuse.

She later excoriated it in her unpublished memoir, No Pleasant Memories. Her

biographer Cassandra Langer summarises it thus: “Brooks had a Gothic childhood

replete with a mad cousin in the attic, an abusive and cruel mother, a

conservative and cold sister and an insane brother.” In 1893, when suffering

neglect from her family while they lived peripatetically in Europe, she

decided to escape to Paris.

1874, Brooks had an unhappy childhood, plagued by physical and emotional abuse.

She later excoriated it in her unpublished memoir, No Pleasant Memories. Her

biographer Cassandra Langer summarises it thus: “Brooks had a Gothic childhood

replete with a mad cousin in the attic, an abusive and cruel mother, a

conservative and cold sister and an insane brother.” In 1893, when suffering

neglect from her family while they lived peripatetically in Europe, she

decided to escape to Paris.

After

some time living and studying in Paris – then later Rome and Capri – Brooks

inherited a large sum of money on her mother’s death. This gave the artist the

financial independence she needed to pursue the development of her craft.

After a brief marriage to gay pianist John Ellingham Brooks in 1903 –

the motives of which still perplex scholars today – she embraced her lesbianism

and increasingly eschewed the physicality of feminine stereotypes in her

artistic work.

some time living and studying in Paris – then later Rome and Capri – Brooks

inherited a large sum of money on her mother’s death. This gave the artist the

financial independence she needed to pursue the development of her craft.

After a brief marriage to gay pianist John Ellingham Brooks in 1903 –

the motives of which still perplex scholars today – she embraced her lesbianism

and increasingly eschewed the physicality of feminine stereotypes in her

artistic work.

She was

one of the first modern artists to depict women’s resistance to patriarchal

representations of the female in art… She understood that women in art had been

treated as objects rather than subjects. She made it her mission to change all

that.

Cassandra Langer

By 1910,

Brooks was a confident artist, working in her – now recognisable – grey

palette. She returned to Paris and put on her first ever solo show at the

Gallery Durand-Ruel. Amongst thirteen paintings, White Azaleas was

the piece that caused a stir. It depicts a nude woman reclining in front of a

series of Japanese style prints, a large bunch of white azaleas beside her.

This nude is remarkable for the subject’s nonchalance: she gazes into the

distance, not seemingly making any concerted effort to entice the viewer.

This painting has often been likened to Manet’s Olympia and Goya’s La maja

desnuda. Whereas these paintings use devices to directly engage the viewer –

and sexually appeal – through pose and eye contact, Brooks rejects the male

gaze. Her painting is radical because it alludes to lesbian desire without

making eroticism the sole focus of the piece. She does not prioritise the

figure, who is simply part of a scene in which the white flowers stand out

among an austere monochrome palette. This indifference to the viewer

pervades her art – in particular, her portraits.

Brooks was a confident artist, working in her – now recognisable – grey

palette. She returned to Paris and put on her first ever solo show at the

Gallery Durand-Ruel. Amongst thirteen paintings, White Azaleas was

the piece that caused a stir. It depicts a nude woman reclining in front of a

series of Japanese style prints, a large bunch of white azaleas beside her.

This nude is remarkable for the subject’s nonchalance: she gazes into the

distance, not seemingly making any concerted effort to entice the viewer.

This painting has often been likened to Manet’s Olympia and Goya’s La maja

desnuda. Whereas these paintings use devices to directly engage the viewer –

and sexually appeal – through pose and eye contact, Brooks rejects the male

gaze. Her painting is radical because it alludes to lesbian desire without

making eroticism the sole focus of the piece. She does not prioritise the

figure, who is simply part of a scene in which the white flowers stand out

among an austere monochrome palette. This indifference to the viewer

pervades her art – in particular, her portraits.

When

Brooks began a lifelong relationship with writer Natalie Barney in 1915, she

was thrown into a social circle of “sexually and financially independent

expatriate women in Paris.” She painted many of them during the 1920s. Indeed,

when Truman Capote visited the artist’s studio in the 1940s he (somewhat

tactlessly) touted it “the all-time ultimate gallery of all the famous dykes from

1880 to 1935 or thereabouts.”

Brooks began a lifelong relationship with writer Natalie Barney in 1915, she

was thrown into a social circle of “sexually and financially independent

expatriate women in Paris.” She painted many of them during the 1920s. Indeed,

when Truman Capote visited the artist’s studio in the 1940s he (somewhat

tactlessly) touted it “the all-time ultimate gallery of all the famous dykes from

1880 to 1935 or thereabouts.”

Throughout

her career, Brooks painted women, and in doing so, molded a new shape for the

21st century lesbian — sometimes sexual, sometimes not, sometime masculine,

sometimes feminine, and not really all too concerned about your prognosis.Priscilla Frank

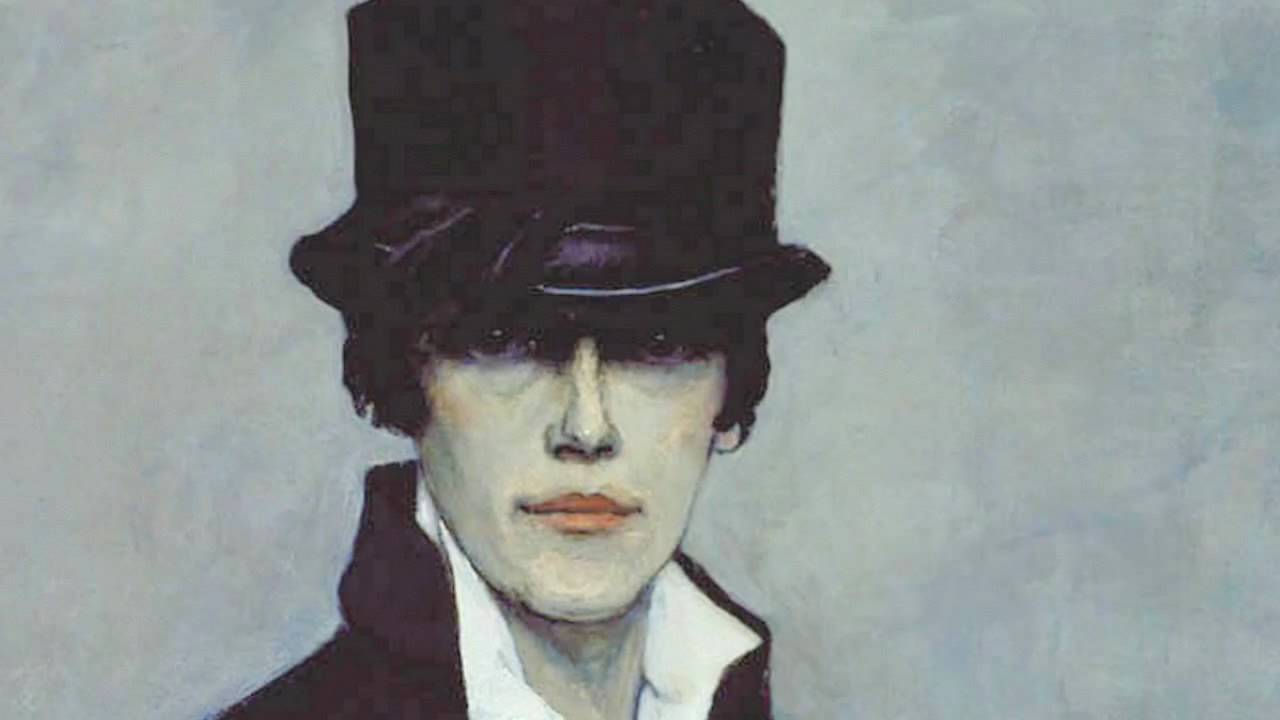

Brooks’

portrait of British artist Gluck, entitled Peter, a Young English Girl, is

beautifully androgynous. Like many of her contemporaries, Gluck had cropped

hair and wore men’s suits as an indication of her sexuality. From a distance,

the sitter looks like a man, but on closer inspection her sharp and delicate

features reveal a femininity. She is self-assured and poised, exquisitely

rendered with Brooks’ favoured grey hues that breathe vitality into her

subjects.

portrait of British artist Gluck, entitled Peter, a Young English Girl, is

beautifully androgynous. Like many of her contemporaries, Gluck had cropped

hair and wore men’s suits as an indication of her sexuality. From a distance,

the sitter looks like a man, but on closer inspection her sharp and delicate

features reveal a femininity. She is self-assured and poised, exquisitely

rendered with Brooks’ favoured grey hues that breathe vitality into her

subjects.

Brooks’

1923 Self-Portrait is similarly angular, androgynous and undeterred by the

viewer. Holland Cotter remarked: “She’s not passively inviting your approach;

she’s deciding whether you’re worth bothering with. Chances are, you’re not, at

least not if you’re approaching with the conventional notions of what male and

female mean.”

1923 Self-Portrait is similarly angular, androgynous and undeterred by the

viewer. Holland Cotter remarked: “She’s not passively inviting your approach;

she’s deciding whether you’re worth bothering with. Chances are, you’re not, at

least not if you’re approaching with the conventional notions of what male and

female mean.”

Though

much of Brooks’ art focused on individual women, she created a series of

drawings that showed a remarkable talent for the surreal. These drawings were

produced alongside her memoirs, and grapple with mythical creatures, angels and

demons. The artist noted that they “evolved from the subconscious without

premeditation.” Unity of Good and Evil (1930-34), is a whirl of restless,

curving lines. Emerging from the flurry are a sleeping mother and child, with

three serpents spitting behind. Whether or not this is the artist contending

with her fraught childhood, as has been interpreted, these drawings are

phenomenal works of art. One scholar notes that they “display a passionate

intelligence that commanded the respect and admiration of some of the foremost

critics of her time.”

much of Brooks’ art focused on individual women, she created a series of

drawings that showed a remarkable talent for the surreal. These drawings were

produced alongside her memoirs, and grapple with mythical creatures, angels and

demons. The artist noted that they “evolved from the subconscious without

premeditation.” Unity of Good and Evil (1930-34), is a whirl of restless,

curving lines. Emerging from the flurry are a sleeping mother and child, with

three serpents spitting behind. Whether or not this is the artist contending

with her fraught childhood, as has been interpreted, these drawings are

phenomenal works of art. One scholar notes that they “display a passionate

intelligence that commanded the respect and admiration of some of the foremost

critics of her time.”

Brooks’

works are a fascinating insight into lesbian subculture in the early twentieth

century, and looking across her incredible body of work is a reminder of the

tragic neglect she’s received from critics in the decades since her death. As

Langer describes, “I always considered her queerness paradoxically essential

and beside the point. The simple truth is she was a great artist whose work has

been misinterpreted and overlooked.”

works are a fascinating insight into lesbian subculture in the early twentieth

century, and looking across her incredible body of work is a reminder of the

tragic neglect she’s received from critics in the decades since her death. As

Langer describes, “I always considered her queerness paradoxically essential

and beside the point. The simple truth is she was a great artist whose work has

been misinterpreted and overlooked.”