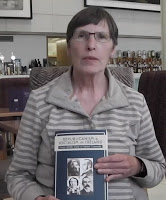

Dr. Priscilla Metscher – “National interests and internationalism do not cancel each other. They should be an important part of left-wing politics todayˮ

by Milena Rampoldi, ProMosaik. In the following my interview with Dr. Priscilla Metscher about socialism, history of socialism, and the challenges of today’s socialism in Europe. Dr. Priscilla Metscher was born in Belfast,

Northern Ireland. She taught Irish studies at Oldenburg University, Germany,

from 1974 to 1999. She has published many articles on the history of radical

Irish politics and is the author of

James Connolly and the Reconquest of Ireland (2002) and Republicanism and Socialism in

Ireland from Wolfe Tone to James Connolly (2016).

Northern Ireland. She taught Irish studies at Oldenburg University, Germany,

from 1974 to 1999. She has published many articles on the history of radical

Irish politics and is the author of

James Connolly and the Reconquest of Ireland (2002) and Republicanism and Socialism in

Ireland from Wolfe Tone to James Connolly (2016).

Why is it so important to study the history

of politics and of political movements, like socialism for example?

of politics and of political movements, like socialism for example?

First of

all I think it is important to study the history of politics and political

movements, as such an insight shows us that the primary motivating force in the

history of class societies is productive relations and ultimately the class

struggle. The centre of that struggle is politically active class consciousness

and political organisation. So ideas as they evolved must be seen within the

context of social and political movements. They cannot be examined as some

abstract ideology apart from their social and political context.

all I think it is important to study the history of politics and political

movements, as such an insight shows us that the primary motivating force in the

history of class societies is productive relations and ultimately the class

struggle. The centre of that struggle is politically active class consciousness

and political organisation. So ideas as they evolved must be seen within the

context of social and political movements. They cannot be examined as some

abstract ideology apart from their social and political context.

Secondly a study of political movements with

special reference to socialism shows us how socialism in the various countries

evolved. The development of socialism in the dominating Western nations has in

many ways a different character from socialism as it evolved in the former

British colonies. Here socialism is connected to the national liberation

struggle, as for example inIreland

Britain

first colony.

special reference to socialism shows us how socialism in the various countries

evolved. The development of socialism in the dominating Western nations has in

many ways a different character from socialism as it evolved in the former

British colonies. Here socialism is connected to the national liberation

struggle, as for example in

first colony.

Also I think we can learn much from the

strength and weaknesses within the various socialist movements. We know e.g.

that at the outbreak of the First World War the socialists in the Second

International were divided over support for the war effort. There were only few

who, when war broke out, vehemently opposed it and called on the workers to

turn the war into civil war for socialism. This was the stand of Lenin inRussia

Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht inGermany Ireland

strength and weaknesses within the various socialist movements. We know e.g.

that at the outbreak of the First World War the socialists in the Second

International were divided over support for the war effort. There were only few

who, when war broke out, vehemently opposed it and called on the workers to

turn the war into civil war for socialism. This was the stand of Lenin in

Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in

On a positive note we see that the Russian

October revolution of 1917 was successful, not only because of the

circumstances existing at the time, but also because Lenin learned from the

failed revolution of 1905.

October revolution of 1917 was successful, not only because of the

circumstances existing at the time, but also because Lenin learned from the

failed revolution of 1905.

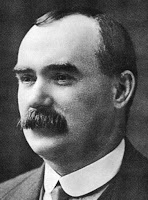

What can we learn

today from James Connolly?

today from James Connolly?

It is important to understand Connolly as a

socialist leader within the context of his time, i.e. the end of the 19th

and beginning of the 20th centuries. His political career corresponds

roughly to the life-span of the 2nd International. I would like to

say a few words about his political career, his Marxism, for these are

essential in assessing his relevance today.

socialist leader within the context of his time, i.e. the end of the 19th

and beginning of the 20th centuries. His political career corresponds

roughly to the life-span of the 2nd International. I would like to

say a few words about his political career, his Marxism, for these are

essential in assessing his relevance today.

He was born in Edinburgh , Scotland

so his first contacts with socialism were in the British labour movement. In

1896 he was offered the job as full-time organiser of the Dublin Socialist Club

and so he came toIreland

Socialism inIreland

had a long tradition, going back to the early Irish socialist William Thompson

at the beginning of the 19th century. Socialist parties and clubs

were in existence when Connolly came toIreland

British parties. They did not have the interests ofIreland

established the Irish Socialist Republican Party as an independent party of the

Irish working class with the goal of establishing an Irish socialist republic.

From the outset Connolly combined socialism inIreland

liberation movement there, going back to the republicanism of the United

Irishmen at the end of the 18th century. He believed it was a

historical necessity for the revolutionary elements in the national movement to

join forces with the Irish working class. This led him, in fact to join forces

with republicans in the organisation and carrying out of the Easter Rising

1916.

so his first contacts with socialism were in the British labour movement. In

1896 he was offered the job as full-time organiser of the Dublin Socialist Club

and so he came to

Socialism in

had a long tradition, going back to the early Irish socialist William Thompson

at the beginning of the 19th century. Socialist parties and clubs

were in existence when Connolly came to

British parties. They did not have the interests of

established the Irish Socialist Republican Party as an independent party of the

Irish working class with the goal of establishing an Irish socialist republic.

From the outset Connolly combined socialism in

liberation movement there, going back to the republicanism of the United

Irishmen at the end of the 18th century. He believed it was a

historical necessity for the revolutionary elements in the national movement to

join forces with the Irish working class. This led him, in fact to join forces

with republicans in the organisation and carrying out of the Easter Rising

1916.

With reference to Connolly‘s Marxism it is

important to emphasise that he was, in the terms of Antonio Gramsci, an

‚organic intellectual‘ of the working class. He did not come from an

intellectual background nor was he a professional intellectual. His education

was mainly autodidactic gained through long hours of study in the National

Library of Ireland inDublin

His work as organiser in political and trade union organisations left him

little time to write. For a time he was organiser of the International Workers

of the World (IWW) in theUSA

popularly known as the Wobblies. The aim of his writings was to develop the

political consciousness of the working class and to aid political action. There

are a number of points which we could take into consideration, essential to

Connolly‘s Marxism, such as his contribution to the concept of historical

materialism, to class as a key concept of social formation and historical

progression, women‘s emancipation, but there are two points which underline

Connolly‘s most original contribution to Marxist theory –firstly socialism and

war and secondly anti-colonialism.

important to emphasise that he was, in the terms of Antonio Gramsci, an

‚organic intellectual‘ of the working class. He did not come from an

intellectual background nor was he a professional intellectual. His education

was mainly autodidactic gained through long hours of study in the National

Library of Ireland in

His work as organiser in political and trade union organisations left him

little time to write. For a time he was organiser of the International Workers

of the World (IWW) in the

popularly known as the Wobblies. The aim of his writings was to develop the

political consciousness of the working class and to aid political action. There

are a number of points which we could take into consideration, essential to

Connolly‘s Marxism, such as his contribution to the concept of historical

materialism, to class as a key concept of social formation and historical

progression, women‘s emancipation, but there are two points which underline

Connolly‘s most original contribution to Marxist theory –firstly socialism and

war and secondly anti-colonialism.

Connolly‘s anti-war stand is of course closely

connected to his support of the struggle of the smaller nations for

self-determination. His stand concerning war is quite clear. On one occasion he

wrote „War is ever the enemy of progress…there are no humane methods of

warfare, there is no such thing as civilised war, all war is barbaric“. One can

certainly place Connolly along with Lenin, Luxemburg and Lebknect on the

left-wing of the Second International. He was quite clear that the First World

War was an inner-imperialist war for the capitalist domination of the world

market, for the political domination of important territory for industry and

finance capital. He participated in the Easter Rising in the hope that in the

end the Rising would lead to the establishment of an Irish Socialist republic.

The fact that the the Rising failed does not diminish the importance of that

anti-colonial struggle. In fact the Easter Rising was not an isolated event,

but was part of a revolutionary wave which occurred not only throughoutEurope , but in other parts of the world up to around

1921.

connected to his support of the struggle of the smaller nations for

self-determination. His stand concerning war is quite clear. On one occasion he

wrote „War is ever the enemy of progress…there are no humane methods of

warfare, there is no such thing as civilised war, all war is barbaric“. One can

certainly place Connolly along with Lenin, Luxemburg and Lebknect on the

left-wing of the Second International. He was quite clear that the First World

War was an inner-imperialist war for the capitalist domination of the world

market, for the political domination of important territory for industry and

finance capital. He participated in the Easter Rising in the hope that in the

end the Rising would lead to the establishment of an Irish Socialist republic.

The fact that the the Rising failed does not diminish the importance of that

anti-colonial struggle. In fact the Easter Rising was not an isolated event,

but was part of a revolutionary wave which occurred not only throughout

1921.

What then

is Connolly‘s legacy? What can we today learn from him? Connolly was convinced

that the example of Irish emancipation could be an attempt to change the map of

world imperialism. If we look at the situation today we see that the inherent

conflict between the interests of world imperialism and those of the smaller

nations has reached a new level of intensity. Paul Ziegler notes that the

society we live in today is a “cannabalistic world order“. I read recently

in an Oxfam report that 62 individuals control more wealth than the bottom half

of the planet‘s population. InEurope alone we

have only to look at the situation inGreece Spain Portugal Ireland

how the smaller nations are dictated to by the imperialist interests within the

EU. I think the left inIreland

and inEurope generally should take up the

interests of these nations and combine them in a programme of alternative

European politics.

is Connolly‘s legacy? What can we today learn from him? Connolly was convinced

that the example of Irish emancipation could be an attempt to change the map of

world imperialism. If we look at the situation today we see that the inherent

conflict between the interests of world imperialism and those of the smaller

nations has reached a new level of intensity. Paul Ziegler notes that the

society we live in today is a “cannabalistic world order“. I read recently

in an Oxfam report that 62 individuals control more wealth than the bottom half

of the planet‘s population. In

have only to look at the situation in

how the smaller nations are dictated to by the imperialist interests within the

EU. I think the left in

and in

interests of these nations and combine them in a programme of alternative

European politics.

What are the main

subjects you treat in your new book Republicanism

and Socialism inIreland

from Wolfe Tone to James Connolly?

subjects you treat in your new book Republicanism

and Socialism in

from Wolfe Tone to James Connolly?

The book examines the history of radical ideas

inIreland

from the emergence of republicanism at the end of the 18th century

up the the Easter Rising of 1916. On the whole I have attempted to show the

interaction of republicanism and socialism in Ireland, indicating how and why

socialism in Ireland has a republican basis.

It was my intention to show the social movements and the accompanying

phenomena of social protest in the context of changing productive relations. So

the rise of Irish republicanism I see in the context of the rise of an Irish

industrial middle class in the 18th century.. Similarly I examine

the growth of radical nationalism at the beginning of the 20th

century within the context of changing agrarian society at the close of the 19th

century, i.e. the development of agriculture on a capitalist basis from

landlordism to a system of peasant proprietorship. The ideas of the United

Irishmen and Young Irelanders, from the end of the 18th century up

to the 1840s are examined against the background of the social conditions of

the period. As far as the Young Irelanders is concerned the potato famine or

the Great Hunger as it is called in Ireland, lasting from 1845 into the 1850s,

plays a significant role. In the years 1845-49 one and a half million Irish

perished of starvation and disease, another one million emigrated, mainly to

theUnited States

Before the Famine Ireland had a population of around eight million. This was

reduced to around four and a half million after the Famine years. The

population in the whole ofIreland

has never reached pre-famine level.

in

from the emergence of republicanism at the end of the 18th century

up the the Easter Rising of 1916. On the whole I have attempted to show the

interaction of republicanism and socialism in Ireland, indicating how and why

socialism in Ireland has a republican basis.

It was my intention to show the social movements and the accompanying

phenomena of social protest in the context of changing productive relations. So

the rise of Irish republicanism I see in the context of the rise of an Irish

industrial middle class in the 18th century.. Similarly I examine

the growth of radical nationalism at the beginning of the 20th

century within the context of changing agrarian society at the close of the 19th

century, i.e. the development of agriculture on a capitalist basis from

landlordism to a system of peasant proprietorship. The ideas of the United

Irishmen and Young Irelanders, from the end of the 18th century up

to the 1840s are examined against the background of the social conditions of

the period. As far as the Young Irelanders is concerned the potato famine or

the Great Hunger as it is called in Ireland, lasting from 1845 into the 1850s,

plays a significant role. In the years 1845-49 one and a half million Irish

perished of starvation and disease, another one million emigrated, mainly to

the

Before the Famine Ireland had a population of around eight million. This was

reduced to around four and a half million after the Famine years. The

population in the whole of

has never reached pre-famine level.

Part II of the book deals with Fenianism and

the Land War as movements essentially of the lower classes. Fenianism developed

out of the previous republican movements. The use of physical force and the

idea of a secret oath-bound society played a major role in the Fenian agenda.

The Land War was an attempt to combine the social and national questions. The

third and final section is entitled „James Connolly, Socialism and the National

Question“. This part could be seen above all within the context of organised

labour history, as it deals primarily with the Irish working class as an

organised class and its role in the political and trade union movements of the

period with a concentration on socialist theory (the development of Connolly‘s

Marxism).

the Land War as movements essentially of the lower classes. Fenianism developed

out of the previous republican movements. The use of physical force and the

idea of a secret oath-bound society played a major role in the Fenian agenda.

The Land War was an attempt to combine the social and national questions. The

third and final section is entitled „James Connolly, Socialism and the National

Question“. This part could be seen above all within the context of organised

labour history, as it deals primarily with the Irish working class as an

organised class and its role in the political and trade union movements of the

period with a concentration on socialist theory (the development of Connolly‘s

Marxism).

On the whole my aim is to show the interaction

of republicanism and socialism inIreland

socialism there has a republican basis. I see James Connolly‘s life and work as

the culminating point in the history of republicanism and socialism in Ireland

up to the present day.

of republicanism and socialism in

socialism there has a republican basis. I see James Connolly‘s life and work as

the culminating point in the history of republicanism and socialism in Ireland

up to the present day.

Where possible I have pointed to the important

role of women in the various organisations, e.g. Mary Anne McCracken, the

sister of Henry Joy McCracken, one of the leaders of the United Irishmen who

was executed in Belfast for his part in the rising of 1798, Fanny and Anna

Parnell, sisters of Charles Stewart Parnell who took over the organisation of

the Land League when their brother, together with Michael Davitt, was

imprisoned. Likewise a number of women were active in the Easter Rising of

1916, such as Constance Markievicz and Winifred Carney (Connolly‘s secretary).

In fact Connolly was of the opinion that women should take their situation into

their own hands and encouraged women to participate in politics- his own

duaghter Nora is a good example. As he aptly wrote: „None so fitted to break

the chains as they who wear them, none so well equipped to decide what is a

fetter“. On another occasion he said: “The worker is the slave of capitalist

society, the female worker is the slave of that slave“.

role of women in the various organisations, e.g. Mary Anne McCracken, the

sister of Henry Joy McCracken, one of the leaders of the United Irishmen who

was executed in Belfast for his part in the rising of 1798, Fanny and Anna

Parnell, sisters of Charles Stewart Parnell who took over the organisation of

the Land League when their brother, together with Michael Davitt, was

imprisoned. Likewise a number of women were active in the Easter Rising of

1916, such as Constance Markievicz and Winifred Carney (Connolly‘s secretary).

In fact Connolly was of the opinion that women should take their situation into

their own hands and encouraged women to participate in politics- his own

duaghter Nora is a good example. As he aptly wrote: „None so fitted to break

the chains as they who wear them, none so well equipped to decide what is a

fetter“. On another occasion he said: “The worker is the slave of capitalist

society, the female worker is the slave of that slave“.

Could you explain

more specifically the term ‚wider class politics‘ to our readers?

more specifically the term ‚wider class politics‘ to our readers?

„James Connolly

and the Wider Class Politics of 1916“ was the title of an article I wrote last

year for the Marx Memorial Library‘s journal „Theory and Struggle” and I

thought it very appropriate to describe Connolly‘s concept of class politics in

this way. Central, of course, to his political thought is the class struggle.

He himself had considerable opportunity to experience this at first hand

throughout his political career in the labour struggles of the time, whether

working for the Industrial Workers of the World in theUSA Dublin

of 1913 when theDublin

employers locked out the workers for six months. But also central to Connolly‘s

political thought was the long-term goal of setting up an Irish socialist

republic and to achieve this it was clear to him that the Irish working class

could not accomplish this alone. So right from the start of his political

activities he was concerned with forming alliances with nationalists who were

not prone to socialism, but who nevertheless regarded Connolly as a reliable

alliance partner in the various anti-British activities inIreland

time. He participated in the ’98 centenary celebrations of the Rising of the

United Irishmen. He was a member of the Transvaal committee opposed to the Boer

war which broke out in 1899 where he worked together with Arthur Griffith (Sinn

Fein) and Maud Gonne McBride. He also helped in the organisation of the

anti-jubilee demonstrations against the reign of QueenVictoria

class politics can be seen in the significance Connolly attributed to the

national liberation struggle and its connection with socialist politics in the

achievement of a socialist republic inIreland

and the Wider Class Politics of 1916“ was the title of an article I wrote last

year for the Marx Memorial Library‘s journal „Theory and Struggle” and I

thought it very appropriate to describe Connolly‘s concept of class politics in

this way. Central, of course, to his political thought is the class struggle.

He himself had considerable opportunity to experience this at first hand

throughout his political career in the labour struggles of the time, whether

working for the Industrial Workers of the World in the

of 1913 when the

employers locked out the workers for six months. But also central to Connolly‘s

political thought was the long-term goal of setting up an Irish socialist

republic and to achieve this it was clear to him that the Irish working class

could not accomplish this alone. So right from the start of his political

activities he was concerned with forming alliances with nationalists who were

not prone to socialism, but who nevertheless regarded Connolly as a reliable

alliance partner in the various anti-British activities in

time. He participated in the ’98 centenary celebrations of the Rising of the

United Irishmen. He was a member of the Transvaal committee opposed to the Boer

war which broke out in 1899 where he worked together with Arthur Griffith (Sinn

Fein) and Maud Gonne McBride. He also helped in the organisation of the

anti-jubilee demonstrations against the reign of Queen

class politics can be seen in the significance Connolly attributed to the

national liberation struggle and its connection with socialist politics in the

achievement of a socialist republic in

I would like to mention Connolly‘s attitude as

a socialist to religion, for it underlines the nature of his alliance policy.

Quite apart from the superfluous question as to whether Connolly was a Catholic

or not, much more important is his stand against those he termed ‚raw atheists‘

in the labour movement who alienated the majority of Catholic workers from the

cause of socialism. InIreland

and in theUnited States

where the majority of Irish workers were Catholic, he realised that it would be

pointless to try winning the mass of Irish people to socialism by putting

himself forward as an atheist. Far from regarding religion as a private matter,

outside the precincts of socialism, he deliberately sought dialogue and

controversy with Catholic priests. Although stressing the

historical-materialist foundation of socialism, he nevertheless maintained that

Christianity and socialism, or within the Irish context, Catholicism and

socialism were not diametrically opposed doctrines, the one negating the other.

Connolly was convinced that Catholicism could not be kept out of the debate on

socialism inIreland

On the contrary, both priests and Catholic laity who actively supported labour

were a possitive asset to the foundation of a socialistIreland

think that Connolly‘s attitude to religion has a lot to tell us today, as to

how socialists should react to the ever-increasing anti-islamphobia – in

Germany as propagated by the AfD and the followers of Pegida and similar

organisations. There are other important matters today where socialist alliance

policy in the sense of wider class politics is essential. In Connolly‘s day the

exploitation of the earth with catastrophic consequences for the ecological

system was not as developed as it is today. The struggle in our times for the

preservation of the earth is essential for the existence of all peoples.

a socialist to religion, for it underlines the nature of his alliance policy.

Quite apart from the superfluous question as to whether Connolly was a Catholic

or not, much more important is his stand against those he termed ‚raw atheists‘

in the labour movement who alienated the majority of Catholic workers from the

cause of socialism. In

and in the

where the majority of Irish workers were Catholic, he realised that it would be

pointless to try winning the mass of Irish people to socialism by putting

himself forward as an atheist. Far from regarding religion as a private matter,

outside the precincts of socialism, he deliberately sought dialogue and

controversy with Catholic priests. Although stressing the

historical-materialist foundation of socialism, he nevertheless maintained that

Christianity and socialism, or within the Irish context, Catholicism and

socialism were not diametrically opposed doctrines, the one negating the other.

Connolly was convinced that Catholicism could not be kept out of the debate on

socialism in

On the contrary, both priests and Catholic laity who actively supported labour

were a possitive asset to the foundation of a socialist

think that Connolly‘s attitude to religion has a lot to tell us today, as to

how socialists should react to the ever-increasing anti-islamphobia – in

Germany as propagated by the AfD and the followers of Pegida and similar

organisations. There are other important matters today where socialist alliance

policy in the sense of wider class politics is essential. In Connolly‘s day the

exploitation of the earth with catastrophic consequences for the ecological

system was not as developed as it is today. The struggle in our times for the

preservation of the earth is essential for the existence of all peoples.

The term ‚post-colonialism‘ is misleading, I

think, as it gives the impression that colonialism is a thing of the past, but

it still exists where trusts and finance capital plunder the resources of the

so-called third world countries, often driving people from the land they have

lived on for generations and cultivated as a means of livlihood. National

liberation struggles continue throughout the world and the struggle for the

upkeep of national sovereignty against world imperialism is of the utmost

importance. So there are many facets to class politics today.

think, as it gives the impression that colonialism is a thing of the past, but

it still exists where trusts and finance capital plunder the resources of the

so-called third world countries, often driving people from the land they have

lived on for generations and cultivated as a means of livlihood. National

liberation struggles continue throughout the world and the struggle for the

upkeep of national sovereignty against world imperialism is of the utmost

importance. So there are many facets to class politics today.

What is the situation today concerning

European socialism? What are the main challenges?

European socialism? What are the main challenges?

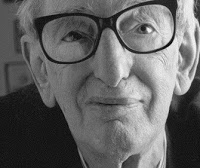

I think concerning socialism in Europe today we have a catastrophic situation . According

to Eric Hobsbawm the left is in a double catastrophic situation. On the one

hand socialism in the formerSoviet Union and

other socialist countries has collapsed and on the other hand traditional

socialist democracy has degenerated into

neoliberalism under the leadership of Blair inBritain Germany

attempt to start again and bring together the various socialist forces has been

hindered by splits within the various left-wing parties inEurope .

Very often it is over the question of participation or non-participation in a

government in which the neoliberal parties have the say. One very interesting

development recently is the left development in the British Labour Party under

Jeremy Corbyn. Since his election to leadership the Labour Party has the

highest membership of all European parties.

to Eric Hobsbawm the left is in a double catastrophic situation. On the one

hand socialism in the former

other socialist countries has collapsed and on the other hand traditional

socialist democracy has degenerated into

neoliberalism under the leadership of Blair in

attempt to start again and bring together the various socialist forces has been

hindered by splits within the various left-wing parties in

Very often it is over the question of participation or non-participation in a

government in which the neoliberal parties have the say. One very interesting

development recently is the left development in the British Labour Party under

Jeremy Corbyn. Since his election to leadership the Labour Party has the

highest membership of all European parties.

Concerning challenges for the left today, I

have already mentioned a few: the struggle for the preservation of the earth,

the struggle against exploitation of trusts and finance capital in their own

and in the third world countries. It is quite clear that we do not have a

revolutionary potential inEurope today, but

there are many forms of struggles within

and outside the EU which in their progressive aspects are also struggles for

self-determination against the reactionary forces of world imperialism. The

left, I think, must bring class politics into these struggles and here the

social question combined with the national question is of paramount importance,

if we are to avoid the national question being exploited by the radical right.

It is not a question of negating the nation, but rather of re-moulding it in

the context of working-class politics.

have already mentioned a few: the struggle for the preservation of the earth,

the struggle against exploitation of trusts and finance capital in their own

and in the third world countries. It is quite clear that we do not have a

revolutionary potential in

there are many forms of struggles within

and outside the EU which in their progressive aspects are also struggles for

self-determination against the reactionary forces of world imperialism. The

left, I think, must bring class politics into these struggles and here the

social question combined with the national question is of paramount importance,

if we are to avoid the national question being exploited by the radical right.

It is not a question of negating the nation, but rather of re-moulding it in

the context of working-class politics.

The aim cannot be the return to traditional

nation states, but must go beyond this and go beyond the present European

Union. A reform within the present European set-up is imposible for obvious

reasons. The aim should be the establishment in the long run of a union of

socialist republics inEurope . This means

ultimately a break with present politics of the European Union rather than an

attempt to ‚reform‘ the EU from within. In the long term then the aim should be

the establishment of a new democratic, socialist order inEurope

and this should occur within the construction of a multi-polar world. In this

context national interests and internationalism do not cancel each other. They

should be an important part of left-wing politics today.

nation states, but must go beyond this and go beyond the present European

Union. A reform within the present European set-up is imposible for obvious

reasons. The aim should be the establishment in the long run of a union of

socialist republics in

ultimately a break with present politics of the European Union rather than an

attempt to ‚reform‘ the EU from within. In the long term then the aim should be

the establishment of a new democratic, socialist order in

and this should occur within the construction of a multi-polar world. In this

context national interests and internationalism do not cancel each other. They

should be an important part of left-wing politics today.

An interesting and encouraging development is

the issue of a declaration recently by left-wing parties acrossEurope . The declaration was issued at the close of an

interparliamentary conference in Brussels on the EUs economic governance

framework and was signed by Podemos and Izquierda Unida (Spain), Syriza

(Greece), Left Block and Portuguese Communist Party (Portugal), die Linke

(Germany), Front de Gauche (France), Red-Green Alliance (Denmark), Sinn Fein

(Ireland) and Akel (Cyprus). Basically the declaration calls for an end to the

EUs neoliberal austerity policies. It calls for a new set of economic, social

and environmental policies in favour of people and workers; public investment

focusing on the creation of decent and secure jobs, strengthening collective

bargaining and collective agreements and extending the right to strike, the

public control and the decentralisation of the banking sector.[1]

This is certainly an important step in combating the rise of the Right

inEurope .

the issue of a declaration recently by left-wing parties across

interparliamentary conference in Brussels on the EUs economic governance

framework and was signed by Podemos and Izquierda Unida (Spain), Syriza

(Greece), Left Block and Portuguese Communist Party (Portugal), die Linke

(Germany), Front de Gauche (France), Red-Green Alliance (Denmark), Sinn Fein

(Ireland) and Akel (Cyprus). Basically the declaration calls for an end to the

EUs neoliberal austerity policies. It calls for a new set of economic, social

and environmental policies in favour of people and workers; public investment

focusing on the creation of decent and secure jobs, strengthening collective

bargaining and collective agreements and extending the right to strike, the

public control and the decentralisation of the banking sector.[1]

This is certainly an important step in combating the rise of the Right

in