Ending the silence around German colonialism

Taylor, May 23, 2016

|

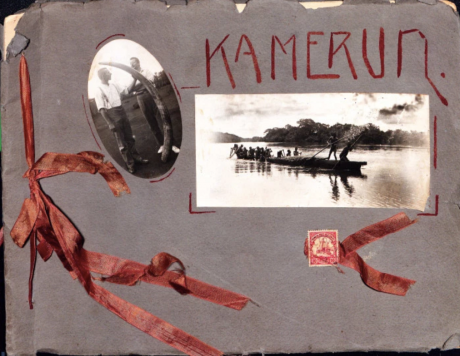

| The ‘Kamerun album’ that kickstarted Colonial Neighbours. Credit: Colonial Neighbours. |

At least 300,000 people died at the

hands of German colonizers during its empire. These art projects are

uncovering colonial histories to understand racism in Germany today.

“It started with an album, called

the Kamerun album, it was given to him by the Grandmother of his

wife, they found it in the attic.”

Lynhan Balatbat works for Colonial

Neighbours , a

Berlin-based art project that collects objects and stories related to

Germany’s controversial colonial past. Lynhan is referring to the

travel journal of a colonial soldier who was based in German

Cameroon. Each photo from the journal provides an unsettling insight

into the world that this soldier saw and took part in colonizing.

Finding this album began a journey

into the homes of many other families in Germany. Colonial

Neighbours is run by Savvy

Contemporary, a Berlin art space initiated by Bonaventure

Ndikung, whose relative the album belonged to. The project’s

endeavour is to bring Germany’s imperial past into the open by making

people think about how it affects their daily lives and how it has

lived on in the present.

As Lynhan says: “I think it’s a very

good way to try to build an alternative narrative. When you

accumulate different stories from different people you give this room

for exchange and through that you create a kind of counter-memory.“

Grassroots projects like Colonial

Neighbours link the struggle to end the active silencing of colonial

history to the struggle against racism in Germany today. If more

people were aware of Germany’s colonial history, they argue,

perhaps they would be aware of the structural processes of racial

othering and alienation that continue in both Germany and its

relationship to the ‘outside’ of Europe.

“What are we doing today?”, Lyn

says, “What were the mechanisms that allowed for the

alienation of someone else and the ability to say that Germany and

Europe had the right to claim: ‘this is ours“.

Keeping secrets

In 1904 in Namibia, the land

of the Herero and Nama was expropriated and thousands were

rounded up and placed in concentration camps. At least 100,000 people

were murdered.

Perhaps you have never heard of German

colonialism; it is less commonly spoken about than other

colonialisms.

The most common reasoning for this is that Germany lost

its colonies too early for them to be of any significance (by 1918).

It is often argued that the empire was short lived, and that it

detracts attention from the crimes of the Second World War to discuss

it.

Yet this narrative ignores the deep

effects that the German empire had on the histories of the places

that it colonized, and the extent to which Germany was caught up in

racist fantasies just as all European countries were, and still to a

certain extent are.

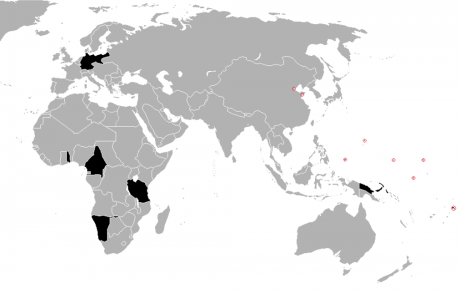

After the Berlin

conference and the ‘Scramble for Africa’ in 1884, Germany

took colonies in East Africa, South West Africa, and North West

Africa. It had protectorates all over the Pacific Ocean, and

territory in China’s Kiatschou bay for 99 years.

At least 300,000 people died at the

hands of German colonizers. In Tanzania in 1905, the

‘Maji Maji’ rebellion against German rule led to retaliation

by German colonists and the enforced starvation of approximately

200,000 people from various different ethnic groups.

The descendants of white German

settlers who took over Herero and Nama land are still in Namibia, and

they continue to own this land, which is 70% of the most productive

agricultural land in Namibia. Colonial rule influenced Germany long

after the territories were lost.

While certainly not equivalent,

there are for example numerous links between German colonial rule and

the Nazis.

One example is German scientist Eugen

Fischer, who undertook medical experiments in Herero concentration

camps. He went on to train Nazi scientists and to write Principles

of Human Heredity and Race Hygiene,

which was hugely influential for Nazi eugenic policy. Fischer also

brought 300 Herero skulls back to Berlin with him.

Only 40 of those

skulls have been returned.

We are used to seeing the racist

crimes of the Second World War as a peculiarly German aberration in

an otherwise general triumph of European civilization.

By calling

attention to German colonialism, that story is de-exceptionalized.

We

see the extent to which German legacies of race have been bound up

with the colonial legacies of Western Europe as a whole.

|

| The German colonial empire 1884-1918 |

Telling secrets

In many major German cities, such as

Berlin, Hamburg, Dresden, Münich, Leipzig, and Frankfurt, grassroots

projects that attempt to inform citizens of that city about their

colonial pasts such as Colonial Neighbours are becoming more and more

prominent. Berlin

and

Hamburg ‘Postkolonial’, for example, conduct different tours

of the city that help attendees to understand the relationship

between locations in Germany

and colonialism. Wherever you

go in Germany, such traces of an actively silenced history exist.

In Berlin, for example, a number of

street names in the city are named after German colonizers. Just

recently on 9 March 2016, “Decolonize

Mitte” (Central Berlin) came one step closer in the attempt to

change

street names that embody a racist and racializing past.

“Lüderitzstraße”, named after Adolf Lüderitz, the founder of

imperial Germany’s first colony, may finally be changed along with

some other street names in the city’s ‘African quarter’.

The government, too, is getting closer

to acknowledging the massacre of the Herero and Nama as a ‘genocide’.

While the UN has been calling this a genocide since as far back as

1948, the German government has never officially recognized it as

such. Last year, the president

of the German parliament argued that Germany should

recognize

the massacre as a genocide.

It has not yet done so.

Germany is no stranger to reparations,

having given large sums of money to descendants of the Jewish victims

of the Holocaust. Yet is has not been forthcoming on the question of

reparations for its colonial crimes. This does not mean that it has

not been demanded.

Such reparative transformation is being argued for

by the direct descendants of the Herero and Nama. In 2001, the Herero

Reparations Committee took the German government and a series of

companies to court in the US. They lost the case, but the fight for

reparation continues.

The future

It has become something of a cliché

to say that colonialism in Europe has been ‘silenced’,

‘repressed’, or ‘forgotten.” Yet such metaphors ignore a

fundamentally important element to the equation: silencing is a

process.

Every single European country that had

colonies has invested energy into the process of silencing and

forgetting the scale of

criminality that was

involved in colonialism.

They

know that to acknowledge the scale of the crimes committed would

involve enormous compensation claims.

Yet as with any attempt to keep a

secret, these processes are always stalled, there has always been

resistance, and right now there is resistance in Germany and in its

former colonies to the process of forgetting its colonial period.

In today’s political climate, in

which Western Europe continues to propagate the myth of itself as

more civilized, more liberal, more tolerant, such resistance is an

important avenue of political hope.

Open Democracy