Interview with Prof. Hans Bjarne Thomsen about “CARA”

by Aygun Uzunlar, ProMosaik e.V. – A very nice interview about our poetry project CARA with Prof. Hans Bjarne Thomsen of the Section for East Asian Art at the University of Zurich who wrote the introduction to the collection of poetry CARA. I would like to thank Prof. Thomsen very much for his time.

Aygun Uzunlar: For

me personally CARA is a way of life of poetry at the interface between

existential philosophy and mystics. How do you see this?

me personally CARA is a way of life of poetry at the interface between

existential philosophy and mystics. How do you see this?

Hans Bjarne Thomsen: I agree, in CARA we see points in common

with both mysticism and existential philosophy.

As we can see in the works of philosophers like Kierkegaard or Sartre,

such concepts are difficult to explain in logical and concise words, and

perhaps this is one of the roles of successful poetry: to make clear that which

is hard to express, in lyrical and moving words. Too often in philosophical texts, we have a

closing of doors: a reduction of possibilities to a path along a long, narrow

corridor. The poetry in CARA does the

exact opposite: it opens doors and

liberates the reader into a rich variety of new possibilities.

with both mysticism and existential philosophy.

As we can see in the works of philosophers like Kierkegaard or Sartre,

such concepts are difficult to explain in logical and concise words, and

perhaps this is one of the roles of successful poetry: to make clear that which

is hard to express, in lyrical and moving words. Too often in philosophical texts, we have a

closing of doors: a reduction of possibilities to a path along a long, narrow

corridor. The poetry in CARA does the

exact opposite: it opens doors and

liberates the reader into a rich variety of new possibilities.

AU:How

important is intercultural and interreligious vision of poetry?

important is intercultural and interreligious vision of poetry?

HBT: Not necessarily important. Great poetry can also be made within

religious traditions and such expressions can be seen, for example, within the

Bible, the Torah, and the Qur’an. Such

poetry tends to be focused closely on small communities within religious systems. Yet, they are undeniably powerful poetic

expressions.

religious traditions and such expressions can be seen, for example, within the

Bible, the Torah, and the Qur’an. Such

poetry tends to be focused closely on small communities within religious systems. Yet, they are undeniably powerful poetic

expressions.

The attraction of the poetry in CARA is

through its almost total lack of connections and contexts. It floats, in a sense, between cultures and

beliefs and forces us to make an effort to understand something that is

essentially fragmentary in nature. In

effect, it expresses the beauty of ambiguity.

And this ambiguity is important for the intercultural and interreligious

vision of this poetry, as well as for the accompanying paintings.

through its almost total lack of connections and contexts. It floats, in a sense, between cultures and

beliefs and forces us to make an effort to understand something that is

essentially fragmentary in nature. In

effect, it expresses the beauty of ambiguity.

And this ambiguity is important for the intercultural and interreligious

vision of this poetry, as well as for the accompanying paintings.

AU:How

can we promote peace by poetry?

can we promote peace by poetry?

HBT: Poetry can certainly promote peace. But we should not forget that poetry remains

a tool in the hands of the poet, and that the intention of the poet remains

important. If the intention of the poet

is to inflame the passions of the readers to the violence of war, then this can

be done: there are plenty of examples of this type of poetry. Just as there are many examples of art that

can bring us to hate, to erotic passion, or to inner contemplation: in all

forms of art, intentions become important.

Poetry, art, and rhetoric: these are all tools in the hands of their

creator and can become as destructive or constructive as willed by the person

who brings them to life.

a tool in the hands of the poet, and that the intention of the poet remains

important. If the intention of the poet

is to inflame the passions of the readers to the violence of war, then this can

be done: there are plenty of examples of this type of poetry. Just as there are many examples of art that

can bring us to hate, to erotic passion, or to inner contemplation: in all

forms of art, intentions become important.

Poetry, art, and rhetoric: these are all tools in the hands of their

creator and can become as destructive or constructive as willed by the person

who brings them to life.

How then can we promote peace? By judicious selections. By selecting the art or poetry that brings out

the better qualities in the readers. Not

a censorship of expression, but a promotion of that which we judge to be for

the better common good. The publication

of CARA is an excellent example: the poetry of the anonymous poet, the

paintings of LaBGC, the work of the editors and publishers ProMosaik – all

these people have come together to make a publication that asks us to

contemplate on vital questions, for example, on our existence, on how to live

with others, and how to communicate, with or without words. Surely these are goals that should be

promoted and those that can lead to peace within ourselves and with others

around us.

the better qualities in the readers. Not

a censorship of expression, but a promotion of that which we judge to be for

the better common good. The publication

of CARA is an excellent example: the poetry of the anonymous poet, the

paintings of LaBGC, the work of the editors and publishers ProMosaik – all

these people have come together to make a publication that asks us to

contemplate on vital questions, for example, on our existence, on how to live

with others, and how to communicate, with or without words. Surely these are goals that should be

promoted and those that can lead to peace within ourselves and with others

around us.

AU: How

important are universal and specific cultural values at the same time to

promote diversity and common values at the same time?

important are universal and specific cultural values at the same time to

promote diversity and common values at the same time?

HBT: This is of course a very topical

question! We see this right now around

us every day, for example, in the question of integration within Europe. Are there universal values that can be

accepted by every culture? Are there

specific cultural values of some groups that make them incompatible when placed

together with other groups? How

important is diversity when it can lead to the tearing apart of common social

fabric? How valuable are common values

when they are the result of sacrifice and suppression of the specific cultural

traditions of some groups?

question! We see this right now around

us every day, for example, in the question of integration within Europe. Are there universal values that can be

accepted by every culture? Are there

specific cultural values of some groups that make them incompatible when placed

together with other groups? How

important is diversity when it can lead to the tearing apart of common social

fabric? How valuable are common values

when they are the result of sacrifice and suppression of the specific cultural

traditions of some groups?

In such questions I believe that it is

important to have a sight of ideals, but – at the same time – to be aware of

the limitations of fellow human beings. It

is clear when we look around in the world that we are not one big happy

family. Conflicts seem to happen

spontaneously across the globe; no area of the world is exempt from this sad

fact. We cannot expect spontaneous

expressions of happiness and peace when we place different cultures next to

each other – especially since cultural values are often based on

differences. That is, a culture

identifies itself though the differences between it and the other cultures and

peoples around itself; differences from the cultural norms of one’s own group

are seen as threatening and as diametrically opposed to the preservation of

one’s own cultural values.

important to have a sight of ideals, but – at the same time – to be aware of

the limitations of fellow human beings. It

is clear when we look around in the world that we are not one big happy

family. Conflicts seem to happen

spontaneously across the globe; no area of the world is exempt from this sad

fact. We cannot expect spontaneous

expressions of happiness and peace when we place different cultures next to

each other – especially since cultural values are often based on

differences. That is, a culture

identifies itself though the differences between it and the other cultures and

peoples around itself; differences from the cultural norms of one’s own group

are seen as threatening and as diametrically opposed to the preservation of

one’s own cultural values.

At the same time, we are now forced to find

common values, and an idealized view of mankind might not be the worst place to

start. By allowing diversity and encouraging

constructive cultural values we may well lead to common understandings. Integration is not a natural tendency, as natural

forces tend to pull us apart. Therefore

process has to be active: we have to continually work against human nature and

reflexive tendencies in order to create a world where both universal and

specific cultural values are appreciated, and where both diversity and common

values are promoted at the same time.

common values, and an idealized view of mankind might not be the worst place to

start. By allowing diversity and encouraging

constructive cultural values we may well lead to common understandings. Integration is not a natural tendency, as natural

forces tend to pull us apart. Therefore

process has to be active: we have to continually work against human nature and

reflexive tendencies in order to create a world where both universal and

specific cultural values are appreciated, and where both diversity and common

values are promoted at the same time.

AU: What

can we learn from the Zen poetry?

can we learn from the Zen poetry?

HBT: Zen poetry is based on the idea of the kōan.

These are the ritualized questions given by abbots to monks during training,

and form an important part of Zen Buddhist belief. The questions might appear to be nonsensical

(Such as the Zen Master Hakuin’s famous kōan: “what is the sound of one hand clapping?”), but the Zen Buddhists

believed that religious awakening could result from the intense study of such

riddles. In effect, the monk is shocked

into awakening.

These are the ritualized questions given by abbots to monks during training,

and form an important part of Zen Buddhist belief. The questions might appear to be nonsensical

(Such as the Zen Master Hakuin’s famous kōan: “what is the sound of one hand clapping?”), but the Zen Buddhists

believed that religious awakening could result from the intense study of such

riddles. In effect, the monk is shocked

into awakening.

The great Zen poets have all undergone this

training, and traces of kōan riddles

appear consequently within the subtext of their poetry. There is a great emphasis on exact wording,

on unexpected twists and turns, and on logic turned on its head. The appeal to modern audiences is

undeniable, as it is a poetic form that gains its power from humor, from

surprise, from tearing up traditions, and on providing fresh views into common

existence. There is indeed much we can

learn from Zen poetry.

training, and traces of kōan riddles

appear consequently within the subtext of their poetry. There is a great emphasis on exact wording,

on unexpected twists and turns, and on logic turned on its head. The appeal to modern audiences is

undeniable, as it is a poetic form that gains its power from humor, from

surprise, from tearing up traditions, and on providing fresh views into common

existence. There is indeed much we can

learn from Zen poetry.

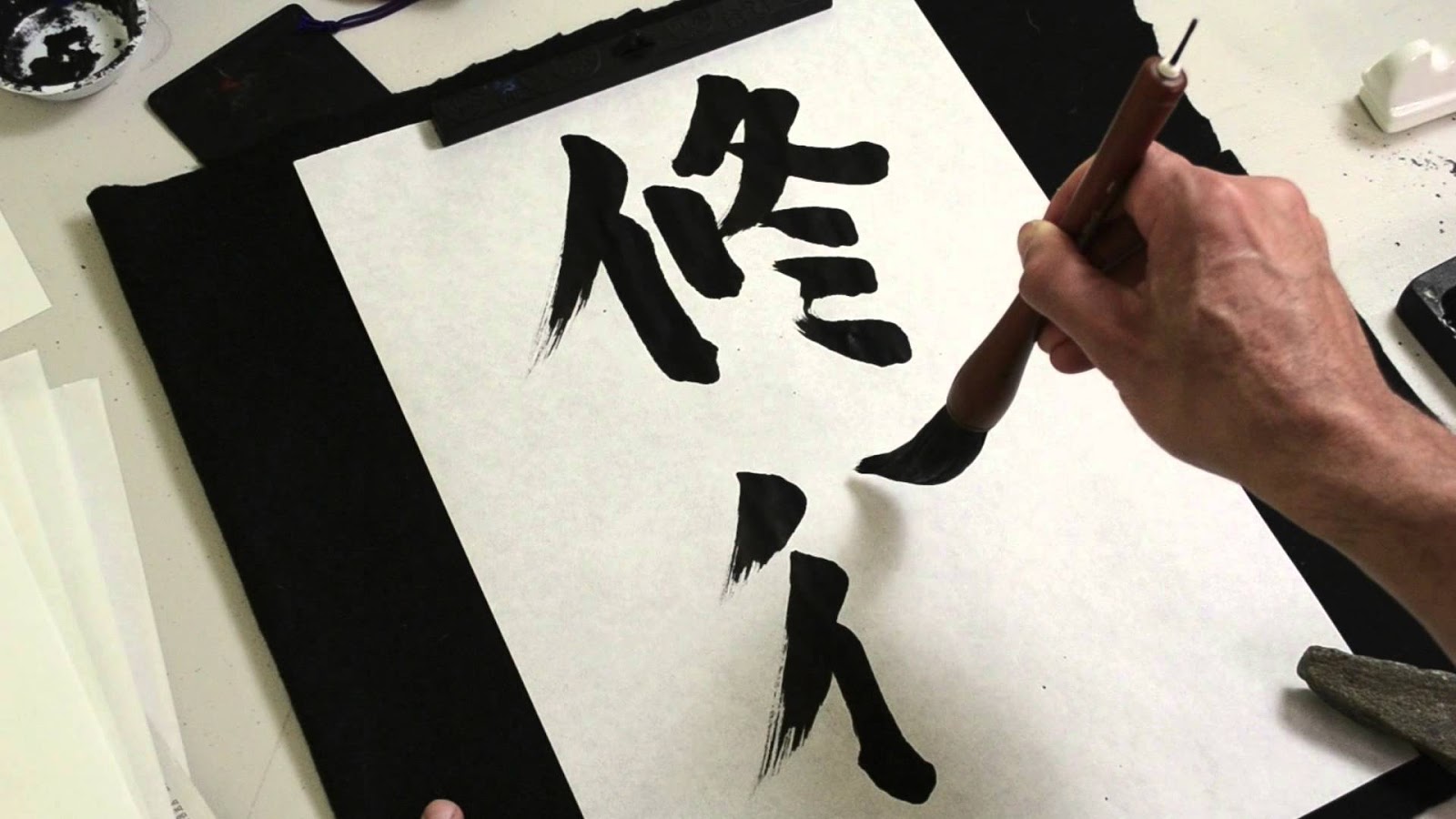

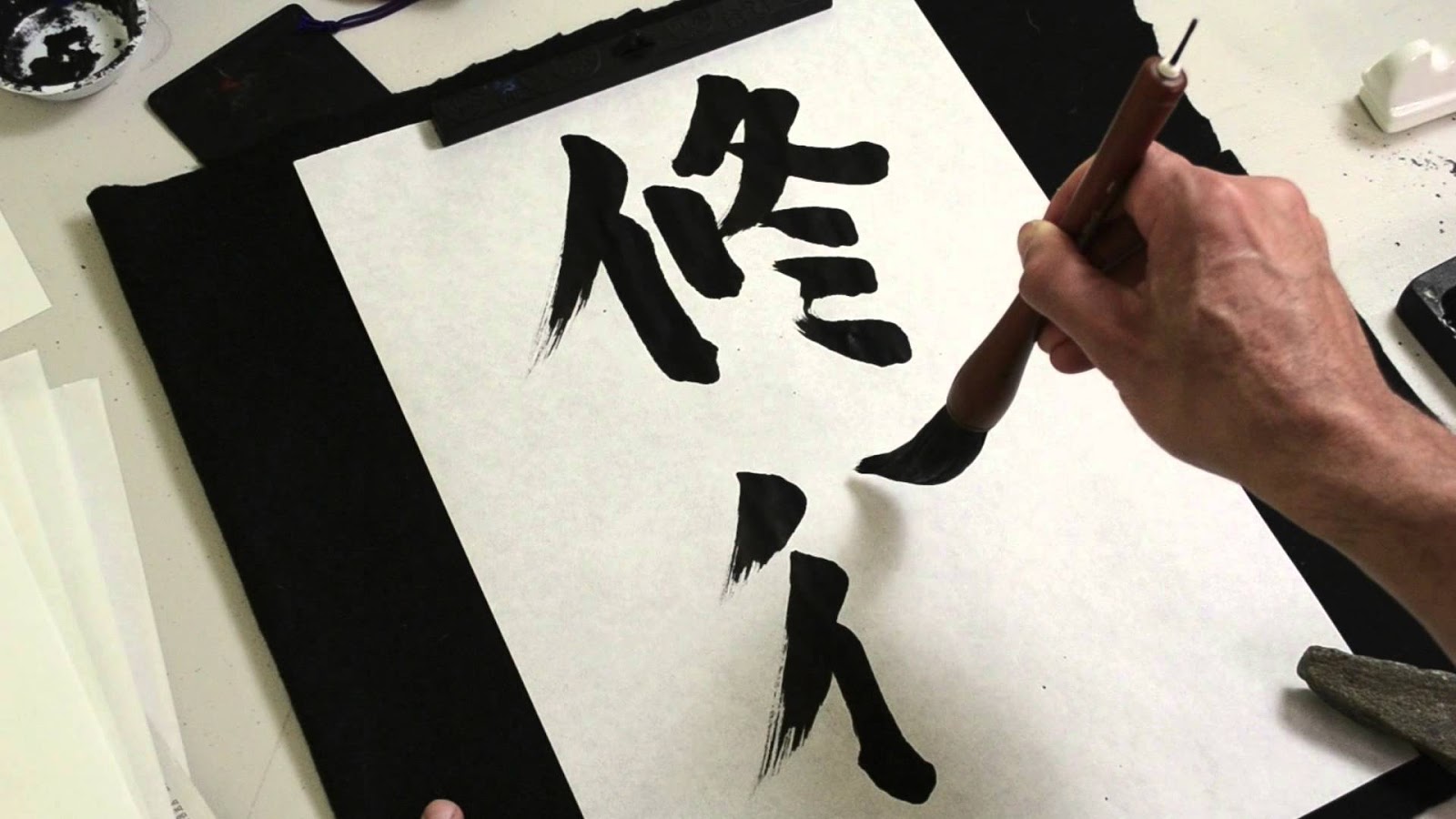

AU: Which

are the most important aspects we can learn from traditional Japanese

calligraphy?

are the most important aspects we can learn from traditional Japanese

calligraphy?

HBT: Japanese calligraphy is a challenging field

to understand. This does not mean that

it is inaccessible – there are indeed aspects that are more easily understood

than others – but it does mean that there are parts of calligraphy that can

only be understood through intense study and through a reading ability of the

text.

to understand. This does not mean that

it is inaccessible – there are indeed aspects that are more easily understood

than others – but it does mean that there are parts of calligraphy that can

only be understood through intense study and through a reading ability of the

text.

We might start with the word “calligraphy”

– from the Latin it means “beautiful writing.” Yet there is nothing inherently

beautiful about Japanese calligraphy. It can be brutal and forceful or elegant

and lyrical: it can charm you with its rhythms or it can slap you in your face:

the emphasis of Japanese calligraphy is on inner strength and not on

beauty.

– from the Latin it means “beautiful writing.” Yet there is nothing inherently

beautiful about Japanese calligraphy. It can be brutal and forceful or elegant

and lyrical: it can charm you with its rhythms or it can slap you in your face:

the emphasis of Japanese calligraphy is on inner strength and not on

beauty.

A Western appreciation of Japanese

calligraphy will include aspects such as the overall expression, the balance of

the lines, the force of the individual strokes, and the modality of the

ink. These are important aspects of the

calligraphy and ones that can be appreciated without a reading knowledge of the

text.

calligraphy will include aspects such as the overall expression, the balance of

the lines, the force of the individual strokes, and the modality of the

ink. These are important aspects of the

calligraphy and ones that can be appreciated without a reading knowledge of the

text.

A Japanese appreciation of calligraphy is

fundamentally different. It will include

the reading of the text: of starting on the first character and then proceeding

through the text. There is a journey

over time from the beginning to the end, touching on all the points in

between.

fundamentally different. It will include

the reading of the text: of starting on the first character and then proceeding

through the text. There is a journey

over time from the beginning to the end, touching on all the points in

between.

The individual characters also have

meanings and the way that the calligrapher expresses these meanings is

significant. He or she could express a

certain character in any number of variations, but a choice is made and the way

that this choice relates to the choices made on characters before or after is

also significant. The understanding of

the audience is based on the reading of words and in the appreciation of how

individual choices were made in depicting these words.

meanings and the way that the calligrapher expresses these meanings is

significant. He or she could express a

certain character in any number of variations, but a choice is made and the way

that this choice relates to the choices made on characters before or after is

also significant. The understanding of

the audience is based on the reading of words and in the appreciation of how

individual choices were made in depicting these words.

Thus there are significant differences in

the way that calligraphy is appreciated in the East and the West. This is not to say that one is correct and

the other is not. Art is in the eyes of

the beholder and the way that calligraphy is appreciated in the West is as

“correct” as it is in Japan. The

importance in this art – as in any other art form – is in the serious

engagement of the viewer and the will to understand. There is much we can learn from traditional

Japanese calligraphy if we are willing to bend our minds.

the way that calligraphy is appreciated in the East and the West. This is not to say that one is correct and

the other is not. Art is in the eyes of

the beholder and the way that calligraphy is appreciated in the West is as

“correct” as it is in Japan. The

importance in this art – as in any other art form – is in the serious

engagement of the viewer and the will to understand. There is much we can learn from traditional

Japanese calligraphy if we are willing to bend our minds.