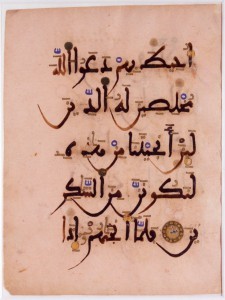

Rabia al-Adawiya: Determined and Strong Muslim Saint

Rabia al-Adawiyya was such an important Muslim Saint

that so many legends were invented to confirm her absolutely pure spirituality,

and the respect of the community towards her reached a level never seen before.

If we consider the age she lived in, we notice how respected religious women

were at her time, compared to the situation many Muslim women must bear in the

West and also at home today.

public, and as soon as they show Islamic spirituality and strong belief, they

are called terrorists or terrorists‘ brides, or supporters of a misogynist

world view opposing to Western democracy and female self-determination. By

using Muslim women as example, the representatives of islamophobia try to

pursue their goal to discredit Islam as religion and culture. All positive

aspects of Islamic spirituality, Islamic values and morality, are completely

ignored. Women who are strong and strongly affirm their own ideas as part of

their Muslim identity are also criticized in their own community. They are

called disobedient women and rebels. The

self-determination we can recognize in Rabia’s life and spirituality which smoothed

her way to Divine Love are very rarely accepted as expression of Islamic

culture and life.

Badawi’s translation into English of the book entitled “Rabia al-Adawiyya:

Martyr of Divine Love” I will present in the present article can contribute to

deeply understand Rabia’s spiritual development, and to understand female

spiritual freedom in Islam. It helps to understand that authentic Islam is not misogynist.

This is one of the philosophical books about Islamic

mysticism that has touched me most in my life as a reader. That’s why I decided

to present it in English.

I believe the author is the Arabic philosopher of

existentialism tout-court. With this booklet, the Egyptian writer and

philosopher Abderrahman Badawi (1917-2002) makes an essential contribution to

interreligious dialogue, in particular with Christianity, offering many

comparative and dialogic approaches within mysticism and spiritual life in

Christianity and Islam, starting from a concept essential to Christianity, that

of Divine Love.

In his research, he compares the great Sufi Saint

Rabia al-Adawiyah and her psychological and theological-philosophical path

towards true Divine Love, as a completely dematerialised experience going

beyond religion as duty and law, with various important thinkers and mystic

pioneers of Christianity like Theresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross, or

notable Christian Saints like Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Augustine of

Hippo.

A second aspect that makes this work fundamental for

Islamic interreligious studies is that Rabia al-Adawiyah was a woman. For

Islamic feminism, she represents an essential model of self-engagement,

braveness, and struggle for female spiritual growth.

Badawi’s work is noted for detailed historical and

philosophical research, a very critical evaluation of hagiographic sources, the

clear distinction between reality and legend, myth and history, and the

importance of spirituality and personal growth in faith.

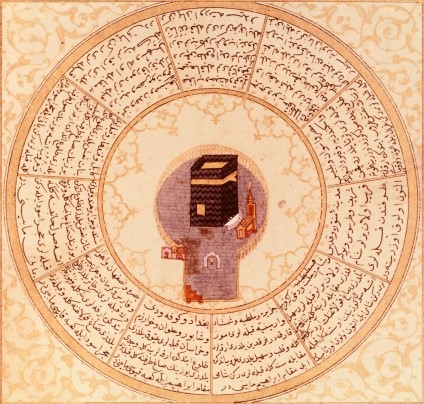

Another important aspect is the concept of

dematerialisation of Islam, initiated by Rabia al-Adawiyah who influenced whole

centuries of Islamic philosophy and mystic thinking. For Badawi, the example of

going beyond the Kaaba and beyond the idea of hellfire and paradise to really

love Allah because of Himself only represents an incredibly developed concept

for that time.

There follows a short summary of all small chapters of

Badawi’s research with an indication of the most important concepts and

arguments he expressed.

In the introduction, the author speaks about Basra and

the soul of its inhabitants, showing how by dismissing legend it is impossible

to understand history, and, without history, it is impossible to understand the

development of spiritual life, which is considered as a process in time.

In chapter 1, Badawi presents the two main

difficulties in researching Rabia’s life: on one hand the scarcity of sources,

and on the other the confusing legends and invented stories to embellish her

theological achievements and spiritual development and perfectness.

The final objective of the author’s work is to

comprehensively show and describe the spiritual development of Rabia

al-Adawiyya, from her life of the earthly life through his conversion until her

perfection as martyr of Divine Love.

Unfortunately, we know very little about Rabia’s life.

Apparently she was born in a poor household, and became a slave who was then

freed. For a while, Rabia worked as a reed pipe player. Her conversion then

followed. Her personality changed completely, by emerging from the dark night

to the light of great souls like St. John of the Cross, St. Augustine and many

other Christian mystics.

In my opinion, Badawi’s approach to spiritual life as

a universal phenomenon can be very useful in promoting interreligious dialogue

between Christianity and Islam. The philosophical method of existentialist

philosophy can be very fruitful for the analysis of internal spiritual development

towards perfectness in Saints and mystics.

Another important aspect I consider very innovative in

this work by Badawi concerns the concept of Divine Love, another subject at the

crosslink of Christian and Islamic Theology. Badawi starts from the basic

assumption that Rabia was a Martyr of Divine Love, and that this Divine Love

was the achievement of spiritual de-materialised perfectness.

This idea is also shown very well in two discourses:

first, the subject about the Kaaba, which has to be controversially

de-materialised to achieve real spirituality. In this context, Islam goes

beyond Judaism and Christianity, which connect worship to a particular place,

while Islam de-materialises spiritual life completely on a topologic level.

Second, the concept of Paradise and Hellfire, which

are completely useless in achieving spiritual perfection. Indeed, Rabia affirms

that those who obey Allah because they fear hellfire are not true believers,

since those who really loves Allah only love Him for Himself, without looking

for any reward, and without being afraid of any punishment.

In the sixth chapter, Abderrahman Badawi introduces

the important biographical problems, with Rabia often confused with another

Rabia, even if for both there are many legends and embellishments to prove

their spiritual achievements and perfectness.

Another important matter Badawi focuses on is the

refusal of married life in Rabia’s sufi mysticism. She is convinced that

marriage would force her to strive for divine love according to Quran and

Sunnah. The same can be said about all worldly and material attachments and

links, even if they are linked to religion like the Kaaba and the belief in

paradise and hellfire. Rabia’s core principle is to love Allah for Himself

without any condition and reward. The Sufi notion of “camaraderie”, explained

in detail by the author, is affirmed by him as an early development of what

will become al-Hallaj’s concept of Divine Love in the future development of

non-orthodox Sufism.

According to the emotional concept of Love in Rabia’s

thought, there is an important distinction to be made between passionate love

on one hand, and true love on the other. Indeed, despite this qualitative

distinction, Rabia used them both, even if she always had in mind that Loving

Allah Himself for nothing but Himself is the highest level of Love of real

believers. In my view, the following passage I would like to mention in the

present foreword can be said to be the core message expressed by Badawi in his

work about Rabia al-Adawiyya:

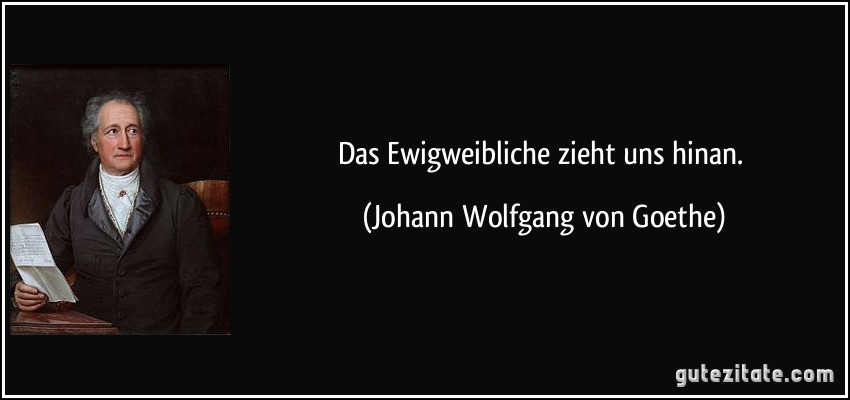

“Then the final stage came by lowering the

curtains of her divine love tragedy by the scene of those angels, i.e. the

women who took her to her final resting place in heaven, like Gretchen in ‘Faust

II’. However, she was not elevated to the high rank by eternal “womanly” (Das

Ewig-Weibliche), but by the martyr-dom of divine love. Anyway, who knows!

Eternal femininity and divine love may be the same!”

I would say that without excluding the possibility

that Eternal femininity and Divine Love could perhaps coincide, Badawi exalts

women’s contribution to Islam not only in the area of mysticism, but in general

Islamic thought and religious culture. Moreover, this is the heritage by Rabia

we have to strongly reaffirm today.

of the extensive legends invented about her life and

deeds also prove her essential importance in Islamic doctrinal development.

Another important aspect inherent in Divine Love

according to Rabia’s world vision is the duality between passivity and

activity. Detaching herself from passionate love to reach the real love of

loving Allah for Himself only was not the last passage she wanted to achieve,

as she additionally strived for active love as product of the passive

experience of Divine Love she had already experienced.

As concerns the explanation of this active love made

of hardship and struggles, Badawi compares Rabia’s experience with the dark

night of Juan de la Cruz, offering us another important thought-provoking

impulse for interreligious dialogue between Christianity and Islam.

In the next chapter, Badawi makes an important

topological distinction between the three monotheistic religions, focussing on

the fact that Islam does not “limit worship to one place, because every place

could be made a house for worshipping Allah.” The thesis the author affirms is

that Rabia revolutionarily transformed Islamic thought by her criticism of the

sensual and material aspects of religion as we have already seen in her

discourse on the Kaaba. Another important element Rabia introduced into Islamic

spirituality was the call for pain, an essential element of the path to Divine

Love. True worship is worship devoted to Allah without seeking rewards or

benefits; it is not because of some religious text or fear; and it is not

because of awakening of desire or fear. It is not because of Paradise or

hellfire. This is the central message of Rabia’s Sufi spiritual conception.