The secret symbols politicians use

di Kelly Grovier, BBC,

15 Aprile 2016

The art works behind world leaders

often contain powerful symbolic messages that are easy to decode,

Kelly Grovier explains.

|

| In front of the unveiling of two Rembrandt portraits, Francois Hollande was transformed into a champion of public culture |

Forget what world leaders say.

If you

want to understand what they are really up to, look at the paintings

that hang behind them at press conferences and summit meetings, or

when they pause with apparent spontaneity along a corridor to answer

a reporter’s question. The silent stare of a poised portrait gazing

at you over the shoulder of David Cameron or Vladimir Putin is often

more loaded and more deliberately orchestrated than you might think.

Often these subtle messages are easy enough to decode.

Consider, for example, a photo-op

earlier this year involving French President Francois Hollande in the

Louvre Museum in Paris. Against the unveiling of two full-body

portraits by the Dutch master Rembrandt that had been in private

ownership for 130 years (the Louvre acquired the paintings jointly

with the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam), Hollande was transformed into a

champion of public culture over the hoarding of art by the rich.

|

| Angela Merkel was pictured with Nelly Toll in front of Girls in the Field, which Toll had painted aged 8 in a Jewish ghetto in Poland (Credit: Rex Features) |

Nor was it difficult to understand why

German Chancellor Angela Merkel was compelled in January 2016 to be

photographed in front of Girls in the Field, a small painting of two

girls in bright flowery dresses.

The work, created in 1943 by

8-year-old Nelly Toll in a Jewish ghetto in Poland, was on display as

part of the

largest exhibition of Holocaust art outside Israel.

At a moment of accelerating

anti-Semitism in Europe, the image of Merkel standing before a

Holocaust survivor’s childhood vision of a peaceful world proved

more eloquent than any speech the leader could hope to deliver.

Seen

side-by-side laughing and shaking hands, Merkel and the now

80-year-old Toll (the only artist in the show who is still alive),

the pair mirrored the joyfulness of the innocent figures in the image

behind them.

New best friends?

Though every world leader is doubtless

conscious of the signals that visual props around them subconsciously

convey, the handlers responsible for shaping the image of the US

president have taken things to another level.

Take President Obama’s

recent trip to Cuba – the first such visit by a US president in 88

years. Obama’s short trek 90 miles (145km) from the US to its

Caribbean neighbour in March 2016 was his boldest step yet in

advancing his controversial agenda to reset diplomatic relations

between the two nations.

But it was a painting by a Cuban artist that

stole the show.

Among the more awkward events on

Obama’s Cuban itinerary was a meeting with a group of political

dissidents, many of whom fear the thawing of relations between

Washington and Havana will only embolden the repressive tendencies of

Cuban president Raúl Castro by legitimising his regime. Enter Michel

Mirabal, a contemporary Cuban artist whose sprawling painting My New

Friend provided the striking backdrop to the meeting.

|

| Michel Mirabal’s My New Friend provided the striking backdrop for Obama’s meeting with a group of political dissidents in Cuba (Credit: Reuters) |

The work, which features side-by-side

representations of the Cuban and US flags constructed loosely of red,

white, and blue handprints pressed haphazardly against a neutral grey

field, stretched evocatively behind Obama as he sat at a long table

to discuss the concerns of the the Cuban government’s detractors.

As a subliminal symbol capable of capturing, on the one hand, the

plight of those oppressed by the Cuban government, and, on the other

hand, Obama’s commitment to ending sanctions against Cuba, the

painting could hardly have been more cleverly chosen.

The hasty

blizzard of anonymous handprints has the feel of street art or

something illicitly constructed: a compression of innocence that

recalls the clay moulds made by children in kindergarten.

At the same

time, the two flags appear to be visual anagrams of each other, each

consisting of the same handprints merely arranged in different

combinations, as if subtly to imply that the two countries are

essentially inseparable.

‘Speak softly and carry a

big stick’

Obama has become a skilled

Curator-in-Chief when it comes to choreographing his events.

On 25

February 2016, the US president reasserted his intention (a key

campaign pledge when he first ran for office in 2008) to close the

detention centre at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, a facility many regard as

emblematic of America’s controversial treatment of terror suspects. Early efforts by Obama to shut the centre met with resistance from

those who argue that the move would send a signal to Islamists that

America’s will to defeat jihadist terror was diminishing.

|

|

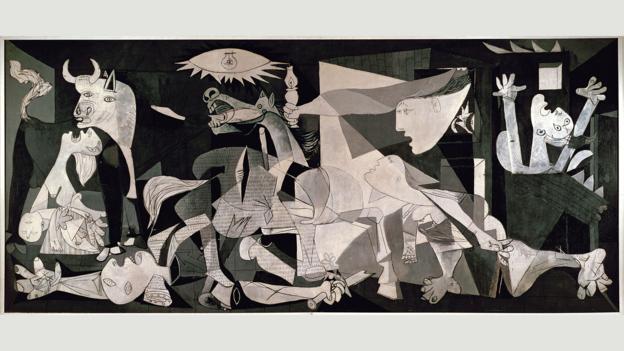

It was deemed too

risky for George W Bush to be pictured in front of Picasso’s Guernica when pressing for war against Iraq (Credit: Guernica, 1937, Pablo Picasso) |

Against the background of such

allegations of weakness, Obama’s decision to hold a press

conference announcing his determination to close Guantanamo once and

for all in the shadow of a swashbuckling portrait of Obama’s

forebear, Theodore Roosevelt, was hardly accidental. After all, Teddy

Roosevelt, who in 1898 led a legendary cavalry of so-called “Rough

Riders” to victory against Spanish overlords in Cuba, helped

establish US control over Guantanamo Bay in the first place.

By

placing himself visually alongside a heroic portrait of the galloping

leader, who is credited with the credo “speak softly and carry a

big stick”, Obama hoped to bask in the reflected testosterone of

America’s most macho president.

Obama’s team is not, of course,

unique among recent US administrations in recognising the power of

art to advance their agendas.

Long before he began, in retirement,

wielding a brush to capture (or torture) the likenesses of the

foreign leaders with whom he dealt as president, George Bush

countenanced an alarming manipulation of aesthetics in order to

control public opinion.

In early February, 2003, when the

United States was pressing the case for war against Iraq in the

United Nations, officials installed a blue curtain across a tapestry

that hangs near the entrance-way of the Security Council, in the very

spot where US State Department Officials are filmed by television

crews.

What work was deemed to be so dangerous that it could not be

transmitted into the living rooms of viewers while Bush officials

lobbied to unleash a campaign of shock and awe against Saddam

Hussein?

The answer is a large tapestry version

of Pablo Picasso’s anti-fascist masterpiece Guernica – an 11ft

(3.4m) wide painting that shudders with the horrors of the aerial

bombardment in 1937 of an ancient Basque town. The original

oil-on-canvas work (which now resides in Madrid’s Reina Sofia

Museum) was on display in New York throughout the violent protests

against the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early ’70s, and was

regarded by many as a painting whose spirit was at odds with the

aggressiveness of US foreign policy.

Thirty years later, Guernica’s

suspended chaos of howling horse heads and ravaged limbs was regarded

by administration officials as too risky a backdrop against which to

be photographed lobbying for war.

The intense relationship between

presidential politics and visual art is due to be given a fresh spin

by whomever prevails in the rambunctious election that is now

gripping the US. If Hillary Clinton wins back the White House for her

family, will her first foray into the politics of the eye be the

swift removal from public display of the official portrait of her

husband that now hangs in the Smithsonian Institute’s National

Portrait Gallery?

In 2015, 10 years after the artist

Nelson Shanks unveiled the likeness of Bill Clinton, Shanks confessed

to having inserted into the work a

covert reference to Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky. And

what if Donald Trump triumphs in November?

His plan to build a wall

1000 miles (1600km) long between the US and Mexico is a graffiti

artist’s dream. If constructed, it would surely result in the

largest blank canvas in the history of Western art.