Tunisia’s last Jewish community dream of a move to Israel

by Daniella Cheslow, June 24, 2016.

|

| A celebration at the Ghriba synagogue in Djerba. Photograph: RFE/RL |

In one of the last Jewish enclaves in the Arab world, families are leaving as tourism declines and security threats intensify.

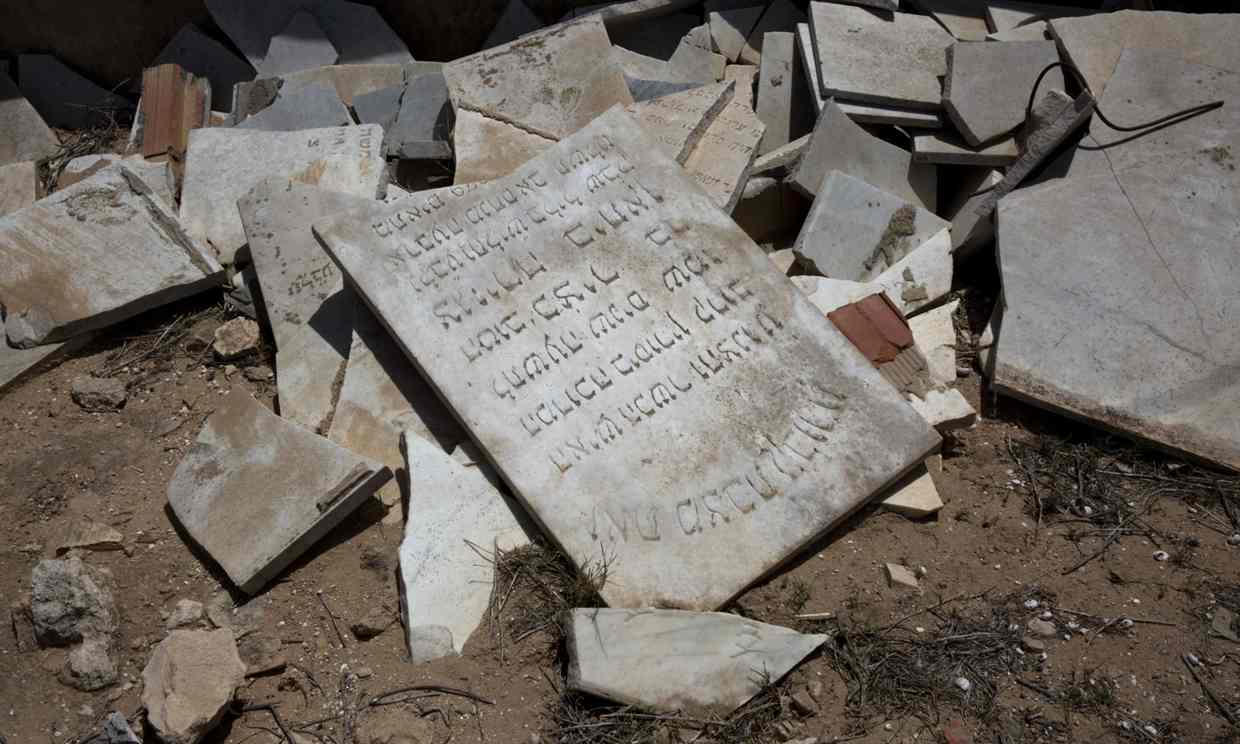

Cracked tombstones litter the cemetery behind Djerba’s Great Synagogue, but it was not vandals who broke them.

Hundreds of Jewish families have moved away from this Tunisian island

community in the past five decades, digging up their relatives’ remains

to take with them and leaving only the slabs of marble behind.

“There are bones that are 80, 90 years old. When you lift them up,

they can break,” says Yossif Sabbagh, a 42-year-old local who helps

exhume around a dozen bodies each year for transport to Israel, where

the majority of Tunisian-born Jews have moved.

This flight of the dead foreshadows a bleak future for the Jews of

Djerba, who trace their arrival on this North African island to more

than two millennia ago, after the sacking of the First Temple in

Jerusalem in 586 BC.

They were once the traditional, observant branch of a vibrant Jewish community that numbered 100,000 across Tunisia. But the 1,100 Jews in Djerba are nearly all that are left after most others fled persecution between the 40s and 60s.

Most of the community has moved to Israel, where as Jews they are

entitled to automatic citizenship, but their exodus could also bring an

end to one of the last Jewish societies in the Arab world.

But there is new life in Djerba, too – about 30 births a year,

according to Tunisia’s chief rabbi and Djerba resident, Haim Bittan. In

comparison, the community in Morocco – the only one in the Arab world

that is larger than Tunisia’s – is mostly elderly. The Egyptian,

Lebanese, and Syrian communities have dwindled to a few dozen, and Jews

are almost gone entirely from Libya and Algeria.

|

| Broken headstones at the cemetery behind Djerba’s Great Synagogue. Photograph: Heidi Levine/RFE/RL |

In late May, crowds filled the ornate white-and-blue tiled Ghriba

synagogue in Hara Sghira, the smaller of two Jewish enclaves in Djerba,

as part of the annual pilgrimage that has long attracted outsiders to

the island.

Pilgrims lit candles in the sanctuary and placed eggs covered with

handwritten wishes in a cave dug into the synagogue’s floor. Across a

cobbled street, revellers sang songs, ate couscous with fish, and drank

fig brandy and beer in a sunny courtyard strung with red Tunisian flags.

The event, marking the Lag BaOmer feast which honours the

second-century Jewish mystic Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, was clearly a

point of local pride.

Back in 2011 the event was cancelled amid the tumult of the Tunisian

revolution that ousted dictator Zine el Abidine Ben Ali, who largely

protected the country’s Jews. It was later restored and the country’s

current government prizes the community as a symbol of stability. But

three major terrorist attacks since the beginning of 2015, along with an

infiltration by the extremist group Islamic State (Isis) just an hour’s

drive south of Djerba, have raised serious security concerns.

This year’s festival took place under intense security, including

checkpoints overseen by special forces and a military truck mounted with

a heavy automatic weapon.

On the first day of the pilgrimage, Abdelfattah Mourou, deputy

speaker of parliament and vice president of the moderate Islamic Ennahda

party, embraced rabbi Bittan outside the Ghriba synagogue.

“Tunisia protects its Jews,” Mourou said. “What leads to radicalism

is having only one culture. Having many cultures allows us to accept one

another.”

The Israeli government was not convinced by the increased security:

in the weeks before the Ghriba festival it issued a travel advisory

warning its citizens to avoid Tunisia. But Perez Trabelsi, the

festival’s 74-year-old president, pointed out that Israel has issued the

same warning each year since the revolution.

“There’s really no danger,” he said. “We have the freedom to leave but we are not going anywhere.”

‘A different world’

Since 2011, Rabbi Bittan estimates that 30 Jews have left Djerba, and

many more are considering moving to Israel, but it’s not for fear of

attack from Islamic extremists, as many suggest.

For Djerba’s Jewish community, it’s about opportunity. Shiran

Trabelsi, 23, teaches fourth grade in Hara Kebira, the larger of the two

Jewish enclaves. She remembers visiting her grandparents in the Israeli

seaside city of Ashkelon in 2006.

“I was in a different world,” she

says. “Over there there’s trees and everything is blossoming and green

and clean. When I got back here, I felt like there’s no colour in the

city.”

Trabelsi said the Jews of Djerba should move to Israel en masse –

although she concedes she would not move without her parents or a

husband.

Kindergarten teacher Yiska Mamou, 24, studied economics in public

school but, like most Jews in Djerba, did not go on to higher education.

She, too, wants to move to Israel, because after work “there’s nothing

to do here but go home and clean.”

|

| A woman leaves eggs inscribed with messages in a cave beneath the synagogue. Photograph: Heidi Levine/RFE/RL |

It’s a lament echoed by many young Jewish women, whose presence is

key to the community’s survival but who pine for Israel’s relative

openness.

Young men, too, dream of moving, but with an eye on economic

security. Like many Jewish men in Djerba, Yoni Haddad is involved in the

jewellery trade. The community is known for its silver filigree and

elaborate, gold-plated wedding headdresses and necklaces that are

popular with Muslim brides, a craft that has been handed down from

generation to generation.

But in recent months Jewish and Muslim shopkeepers alike have

suffered heavy losses as tourists abandon Tunisia after Isis-affiliated

gunmen attacked a beach hotel in Sousse in the summer of 2015, killing 38 people, mostly British tourists.

For Yigal Palmor, spokesman of the Jewish Agency, a

quasi-governmental organisation that promotes immigration to Israel,

it’s this uncertainty, both economic and political, that makes moving to

Israel more attractive. “There is very little future for any Jewish

community in any Arab country unless things change dramatically. Even if

they are tolerated, I don’t believe they have a real future there,” he

says.

For now, Djerba’s Jews are grooming the next generation for a split

identity. On a Thursday afternoon, Elinor Haddad, 16, mops the kitchen

of her family home in preparation for the weekend. Her older brother has

just returned from a sponsored trip to Israel, and Elinor wears a

bracelet he bought her as a gift. She would not be making the same trip,

she said, because Rabbi Bittan ruled against girls travelling alone.

To avoid assimilation into Tunisian society, Haddad’s girls-only high

school teaches an Israeli curriculum. Haddad speaks fluent Hebrew along

with Arabic. Israeli mores have seeped into home life as well. Friday

night dinner at Haddad’s house would be the traditional Tunisian Jewish

meal of couscous, but Thursday’s lunch was chicken schnitzel – a common

Israeli meal imported by European Jewish immigrants.

On Thursday night, Elinor giggles with friends in the Ghriba

synagogue’s anteroom while pilgrims passed by. Ordinarily, she said, she

sits with friends behind closed doors. The pilgrimage is a chance to

see and be seen, she said. “If I had the opportunity to move to Israel I

would go,” Haddad says. “But it’s ok here too.”

At the cemetery, Sabbagh said he had also considered moving to

Israel, but hesitated because of the higher cost of living. When his

father died, Sabbagh and his siblings flew the body to Israel and buried

him in Jerusalem. But for the older tombs, he says. “I think the bones

should stay in their graves.”

A version of this article first appeared on RFE/RL