European Governments Want To Combat Terrorism With Prison Segregation, Solitary Confinement

‘Prisons will never provide the solution to the

problem’ of terrorism, The Guardian warns in an editorial. ‘But it is right to

expect the prisons not to make the problem worse.’

problem’ of terrorism, The Guardian warns in an editorial. ‘But it is right to

expect the prisons not to make the problem worse.’

A prisoner shields

his face as he peers out through the so-called “bean hole” which is used to

pass food and other items into detainee cells, at Camp Delta detention center,

Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base, Cuba. (AP/Brennan Llinsley)

his face as he peers out through the so-called “bean hole” which is used to

pass food and other items into detainee cells, at Camp Delta detention center,

Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base, Cuba. (AP/Brennan Llinsley)

AUSTIN, Texas — British and French prisons may

soon employ controversial methods like solitary confinement and

‘terrorist-only’ units in an effort to curb radicalization efforts in prisons

and to keep inmates from turning to terrorism.

soon employ controversial methods like solitary confinement and

‘terrorist-only’ units in an effort to curb radicalization efforts in prisons

and to keep inmates from turning to terrorism.

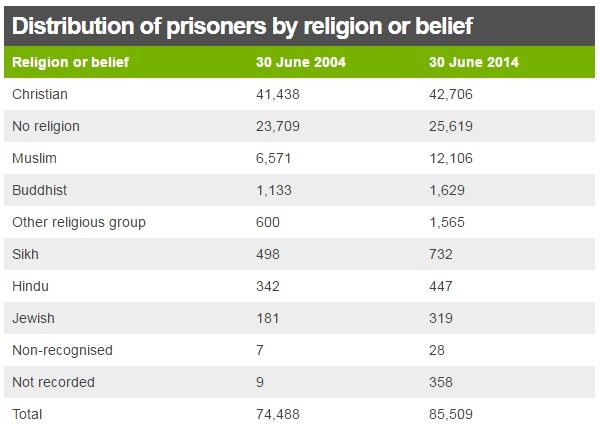

Compared to their overall

populations, England, Wales and France disproportionately imprison Muslims. A

study conducted in March 2015 found that the number of Muslim prisoners in

English and Welsh prisonsincreased 122 percent between

2002 and 2014, while the total number of prisoners only increased 20 percent

over the same time period.

populations, England, Wales and France disproportionately imprison Muslims. A

study conducted in March 2015 found that the number of Muslim prisoners in

English and Welsh prisonsincreased 122 percent between

2002 and 2014, while the total number of prisoners only increased 20 percent

over the same time period.

And although French laws prevent

an exact count of Muslims in prison, it’s estimated that as many as 70 percent of the country’s 67,500 prisoners are Muslim.

an exact count of Muslims in prison, it’s estimated that as many as 70 percent of the country’s 67,500 prisoners are Muslim.

In July, Anjem Choudary, a self-styled Muslim preacher

living in Britain, was convicted of supporting Daesh (an Arabic acronym for the

terrorist group commonly known in the West as ISIS or ISIL). His sentencing is

scheduled for Sept. 6, and he faces up to 10 years in prison. Choudary’s

conviction highlighted concerns from some in government that he and others like

him could spread extremist philosophies to the rest of the general prison

population.

living in Britain, was convicted of supporting Daesh (an Arabic acronym for the

terrorist group commonly known in the West as ISIS or ISIL). His sentencing is

scheduled for Sept. 6, and he faces up to 10 years in prison. Choudary’s

conviction highlighted concerns from some in government that he and others like

him could spread extremist philosophies to the rest of the general prison

population.

A recent report by the British Ministry

of Justice raised the alarm about the problem of terrorist recruiting in

prison, including revealing evidence of a flourishing “Muslim gang culture” and

swelling support for Daesh in prisons. As a result, there’s growing talk

of creating special unitsmodeled after Dutch prisons which take those prisoners who are on remand for, or already

convicted of, terrorism-related charges out of the general prison population.

of Justice raised the alarm about the problem of terrorist recruiting in

prison, including revealing evidence of a flourishing “Muslim gang culture” and

swelling support for Daesh in prisons. As a result, there’s growing talk

of creating special unitsmodeled after Dutch prisons which take those prisoners who are on remand for, or already

convicted of, terrorism-related charges out of the general prison population.

However, these units, which would

be filled based on religious profiling efforts, could “provide a focal point

for public protests and claims of a ‘British Guantanamo,’” as The Guardian’s Rajeev Syal reported on Aug. 22. Further, they

could actually serve to strengthen dangerous groups, rather than curb their

growth.

be filled based on religious profiling efforts, could “provide a focal point

for public protests and claims of a ‘British Guantanamo,’” as The Guardian’s Rajeev Syal reported on Aug. 22. Further, they

could actually serve to strengthen dangerous groups, rather than curb their

growth.

“The experience at the Maze prison in Northern Ireland in

the 1980s, where republican and loyalist prisoners organised themselves along

military lines and ran their respective H-blocks, is often cited as the main

argument against a separatist solution,” Syal reported.

the 1980s, where republican and loyalist prisoners organised themselves along

military lines and ran their respective H-blocks, is often cited as the main

argument against a separatist solution,” Syal reported.

Another plan proposed by the

Ministry of Justice would see certain inmates — particularly, those deemed most

dangerous — constantly shuffled between isolation units in different

prisons, The Guardian also reported on Aug. 22.

Ministry of Justice would see certain inmates — particularly, those deemed most

dangerous — constantly shuffled between isolation units in different

prisons, The Guardian also reported on Aug. 22.

But while keeping prisoners on

the move has a long history, known colloquially in the United Kingdom as the

“magic roundabout” or the “shared misery circuit,” and as “Diesel Therapy” in the United States, the

practice carries with it considerable human rights concerns. Prisoners in transit can spend hours on buses

with poor climate control, and they are often kept shackled in order to prevent

anything but the most limited range of motion.

the move has a long history, known colloquially in the United Kingdom as the

“magic roundabout” or the “shared misery circuit,” and as “Diesel Therapy” in the United States, the

practice carries with it considerable human rights concerns. Prisoners in transit can spend hours on buses

with poor climate control, and they are often kept shackled in order to prevent

anything but the most limited range of motion.

Britain’s Kate,

Duchess of Cambridge arrives for a visit to Her Majesty’s Prison Send near

Woking, England, Friday, Sept. 25, 2015.

Duchess of Cambridge arrives for a visit to Her Majesty’s Prison Send near

Woking, England, Friday, Sept. 25, 2015.

Similarly, long-term solitary

confinement can do severe harm to prisoners’ mental health. The United Nations has repeatedly raised concerns about the use of solitary confinement in the U.S., and argued that its use should be limited to

15 days or less.

confinement can do severe harm to prisoners’ mental health. The United Nations has repeatedly raised concerns about the use of solitary confinement in the U.S., and argued that its use should be limited to

15 days or less.

In February, France began

creating separate “anti-radicalization” units for prisoners suspected of

harboring terrorist sympathies. According to a report from The Guardian, these units focus on

providing education and cultural alternatives to terrorism.

creating separate “anti-radicalization” units for prisoners suspected of

harboring terrorist sympathies. According to a report from The Guardian, these units focus on

providing education and cultural alternatives to terrorism.

“The routine for these men will

include theatre workshops, political discussions and lessons in the prison

school – reading and writing for the barely literate, Japanese for the intellectually

advanced,“ Christopher de Bellaigue reported in March.

include theatre workshops, political discussions and lessons in the prison

school – reading and writing for the barely literate, Japanese for the intellectually

advanced,“ Christopher de Bellaigue reported in March.

In an Aug 22. editorial, The

Guardian’s editorial board warned of the drawbacks of strategies like “magic

roundabouts” and separate units.

Guardian’s editorial board warned of the drawbacks of strategies like “magic

roundabouts” and separate units.

“None of these courses of action

is a guaranteed success,” they wrote. “None of them is cheap. Each

is further complicated by the need to apply the strategy to [prisoners awaiting

trial], young prisoners and women.”

is a guaranteed success,” they wrote. “None of them is cheap. Each

is further complicated by the need to apply the strategy to [prisoners awaiting

trial], young prisoners and women.”

Ultimately, they argued that

solutions to the problem of terrorism and extremism must come from outside

prison walls:

solutions to the problem of terrorism and extremism must come from outside

prison walls:

“Prisons will never provide the

solution to the problem … That lies outside the prisons, not inside them. It

will be the work of generations. But it is right to expect the prisons not to

make the problem worse.”

solution to the problem … That lies outside the prisons, not inside them. It

will be the work of generations. But it is right to expect the prisons not to

make the problem worse.”