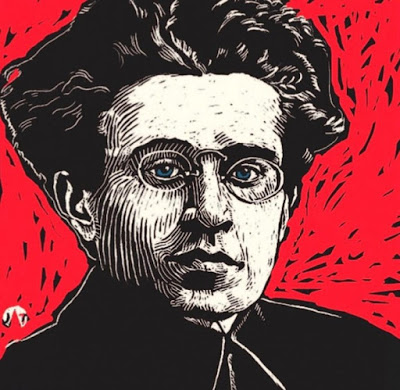

Happy Birthday, Antonio Gramsci

|

| Lorenzo Alfano 27/01/2020 |

Antonio Gramsci is remembered as a great theorist of modern politics and culture. But he didn’t think big ideas were just a matter for intellectuals — and he insisted that workers must become the leaders of their own organizations.

Tradotto da David Broder

It’s late at night on Turin’s Via dell’Arcivescovado. A man with a Southern accent shows up at L’Ordine Nuovo’s office, insisting on speaking with the lead editor. For L’Ordine Nuovo is not only the workers’ daily, but also the paper of Antonio Gramsci.

Yet the political climate here in Turin at the start of the 1920s is tense — every night, factory workers do shifts on guard duty to defend the building’s doors. Everyone expects that sooner or later the fascist squads will turn up to wreck the place.

The building is fortified. The workers are armed, and in between the main entrance and the editors’ offices there is a long corridor, a courtyard, a gate, barbed wire, large metallic obstacles, grenades, and machine guns — or so they claim.

The guard on shift looks the man up and down. He sounds like he’s from Naples. But maybe he’s a FIAT company spy, a fascist, or a policeman (or all three). The guard tells him that if he wants to speak with Gramsci, he’ll have to wear a blindfold, so he doesn’t see the defenses.

The “suspicious” visitor is furious — and he turns to leave. But after a few steps, he turns around again and shouts, “Tell Gramsci that Benedetto Croce came for him!”

Gramsci was disappointed to have missed him. But he also laughed — he could hardly imagine Italy’s then most renowned intellectual stumbling around blindfolded looking for Antonio. And he laughed because he was a man of simple humor: sociable, smiling, who often burst out in childish laughter that put everyone in a good mood.