The Way Ahead for a UN Treaty on Business and Human Rights

|

| ANTONELLA ANGELINI – FEBRUARY 28, 2019 |

We still have a very limited understanding of the impacts businesses have on human rights worldwide.

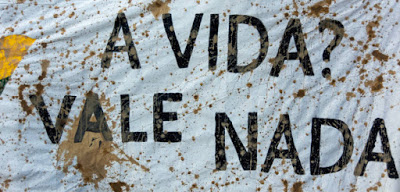

It has been just over a month since the Brumadinho dam, operated by the Brazilian minerals form Vale, collapsed, killing at least 171 people, with a further 141 still missing. In the wake of what appears to be yet another disaster heavily abetted by the failures of business, news from the Geneva headquarters of the United Nations may seem remote and out of touch. Important developments, however, are brewing there.

On February 6, a noteworthy one-page document came out — a call for comments on the international instrument that might be a game changer where, like in the Brumadinho disaster, corporations are involved in human rights abuses and affected communities and individuals seek access to effective remedies.

The call, addressed as it is to states and other relevant stakeholders, picks up on and seeks to revive the momentum and participation of the past months. October 2018 saw a whopping number of 94 states and 400 civil society organizations participate in the fourth session of the UN intergovernmental working group tasked with developing a binding treaty on business and human rights. This high participation reflects the fact that, unlike in previous sessions, a first-ever full negotiating text — a “zero draft” treaty and a “zero draft” optional protocol — was finally on the table. The draft treaty in particular had already drawn much attention as soon as it went public in July, and a very focused scholarly and policy discussion has thrived ever since.

GOOD NEWS?

If all this is good news, the question of whether the treaty initiative has moved past the mire into full maturity is still up for debate. The first reading of the draft treaty and the quick skim of the draft optional protocol brought to light all sorts of issues, from open disagreement among states to coolness toward the drafting choices of the working group. More concerning, however, at least in the immediate term, are the cracks in the support for the current form of the treaty process.

While all BRICS countries and many states from the so-called “global south” contributed, Western states — including the European Union, the US and Australia — were either absent or dissociated themselves from the conclusions of the October session. The EU in particular rubbed salt into the wound by pointing to the many open issues and the virtual boycott by major Western states as signs of dwindling faith in the leadership of the working group.

The call was thus for seeking guidance from the Human Rights Council as the authoritative body on the treaty process — and quite sensibly so, in principle, as a renewed mandate would likely help the legitimacy of the working group. At the same time, in today’s shifting political sands, particularly for the Latin American membership of the council, obtaining a new resolution would be highly volatile. The EU’s insistence on such a solution thus lends itself to two readings. It is either a tactic to remain at arm’s length from negotiations or a way to keep the legitimacy issue alight and let it fester until it blows up into an unavoidable roadblock.

The one sure thing is that the working group will need a great deal of negotiating dexterity to avoid worsening its position. For the issues to juggle are not only about transparency, inclusiveness and conflict avoidance. They are also about sorting out priorities and devising a more effective language to convey them. The October talks left no doubt indeed that the current draft treaty needs more than a tweak. Many provisions invited criticism of lack of clarity and potential incoherence, and broad phraseology had a chilling rather than a reassuring effect on states. Progress on language was therefore slow — particularly concerning non-terms of art, such as the “business activities of a transnational character” formula that should delimit the scope of the draft treaty.

To a certain extent, this is not surprising. Detailed discussions about definitions would have been unlikely at this still highly contested stage of negotiations. But as other commentators have noted, that is not all. Some key provisions of the draft treaty eluded clarification because they are hard to operationalize for the purposes of monitoring and attributing legal liability. And this is so because the draft treaty has still too loose a grip on the complexity of global supply chains.

If it persists, this issue could derail the treaty process. It already did enough chipping away at both minimal consensus on controversial areas and deeper convergence on broadly shared objectives. Take two examples: the focus of the draft treaty and the prevention of human rights abuses by business. The first confirmed itself as the one most tangible and persistent item of disagreement between states. Once again, the division was along the lines of what types of corporations the treaty should include — a division that in turn reflects deeply entrenched development concerns.

Most Latin American states insisted on the need to focus, like the UN Guiding Principles (UNGPs), on all business enterprises. States that are home to fewer multinational companies — such as Indonesia, Egypt and the Philippines — blended their support for the draft treaty with a veiled defense of the special position of national small and medium enterprises. Others still reiterated a more open support for a primary focus on transnational corporations. But very few zeroed-in on the actual language of the draft treaty that speaks of for-profit business activities of a transnational character.

HYBRID SOLUTION

In principle, this formula neither limits the scope to transnational corporations, nor does it include all business enterprises. It rather proposes a hybrid solution based on the nature of the activity concerned. It is thus telling that, innovative as it is in its approach, the draft treaty still brought only limited perspective to the debate, and surely not enough to break the deadlock. Its language proved indeed slippery even for the experts invited by the working group.

How does one realistically define the scope of the treaty in cases where there is only an occasional activity, rather than a long-term business relationship, of a transnational character, or where it only involves the selling of certain goods or services to clients in a foreign jurisdiction? How do we cope with the likely loopholes to which the focus on “transnational character” lends itself, and which business can exploit to avoid liability in terms of the treaty?

The point here is that, because business can morph easily, the transnational-local dimension is hard to translate into legal and operational meaning. Add to that the risk of domestic legislations defining inconsistently the transnational character of an activity, and one is left with serious legal uncertainty as to the scope of jurisdiction of the treaty. This is not to say that feasible solutions are out of reach. Professor Surya Deva, of the City University of Hong Kong, suggested that “while the main treaty could apply only to TNCs and other business enterprises with a transnational character, an optional protocol could extend its relevant provisions to all other types of business enterprises.”

Whatever the arrangement, it needs to come with enough realistic guidance from the working group. Last October, this was not the case, and states persisted in their worn-out attitudes. For similar reasons, the drafting choices of the working group fell short also on less divisive and divided issues. Prevention is a good example. Despite the general buy-in from states, progress was slow toward operationalizing human rights due diligence as a mandatory duty for business. Several states feared inconsistency between the definitions of terms contained in the draft treaty and that of the same terms in the UNGPs. But there was more than drafting sloppiness at play against consensus building.

According to the draft treaty, due diligence duties shall apply throughout a company’s business activities of a transnational character, and failure to comply with them shall entail commensurable liability and compensation. This is problematic considering our still limited understanding of the human rights impacts of businesses.

FINE LINE

Regrettably, as the Working Group on Business and Human Rights noted in its report to the 2018 UN General Assembly, we still have scarce “comprehensive and systematic data on how the majority of the world’s business enterprises understand and manage their actual and potential adverse impacts on human rights.” There are some emerging good practices. One approach to issues relating to supply chains, notes the 2018 report on due diligence, is cascading — requiring or setting incentives for immediate business partners to carry out human rights due diligence, incentivizing the tier-one suppliers with their own supply chain and so on.

That said, states remain under and ill-equipped for overseeing on corporate human rights due diligence. The current dearth of good practice guidance poses a serious, and yet once again understated, challenge for a treaty requiring capacity building by governments or corporations.

That said, states remain under and ill-equipped for overseeing on corporate human rights due diligence. The current dearth of good practice guidance poses a serious, and yet once again understated, challenge for a treaty requiring capacity building by governments or corporations.

All this shows that there is a gap between the business and human rights nexus in reality, and the working group’s vision for regulating it through the treaty. This gap could make the treaty process unfit to reflect both existing and future challenges. On this last point, think for instance of the very ambiguous exclusion of state-owned enterprises with a not-strictly for-profit mission. With the increasing significance of SOEs in global economy, the issue is likely to become hotter than it was last October.

Back in 2015, at the time of the adoption of the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, commentators lamented the continuing chasm in discourse and debate between the business development and the business human rights communities. The same chasm seems to persist in the treaty negotiation. There is a fine line between vision and practicality, particularly when reality is complex and its understanding is patchy. The working group will have to walk that fine line wisely when, at the end of this month’s window of gathering comments, it will resume its behind-the-scenes work.

The same reminder applies to civil society. The risk of shrinking space for the entire treaty process calls for civil society organizations to concentrate their advocacy in areas that may have more immediate buy-in by states. For instance, states proved very skeptical toward a body responsible for the implementation of the future treaty, which was already a very low-profile solution — albeit much needed, deeper reflection on this point is perhaps not for now. Priority should go to issues, such as due diligence and legal liability, where there are enough germs of consensus to hope that the multiple deficits of the treaty process will not sink it completely and that in the future, victims of disasters like the Brumadinho dam collapse will have better recourse to justice.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.