Palestinians were right to reject partition

|

| Fathi Nemer – September 24, 2018 |

The Trump presidency has been very good for Israel. Settlement construction is booming, the annexation of occupied East Jerusalem has been legitimized, and even attempting to discuss Israel’s obligations under international law is met with extreme hostility.

Although previous US administrations always provided cover for Israel, they still sometimes managed to slip in an ode to human rights and feigned ‘concern’ regarding Israel’s constant violation of international law. Naturally, this never really changed Israeli policy in any meaningful way. Even the Obama administration, which many absurdly labeled ‘anti–Israel,’ still managed to approve a whopping 38 billion dollar military aid package to Israel.

Yet in today’s international climate, even these empty words or merely acknowledging the rights and dignity of Palestinians are deemed a step too far. Under such circumstances and complete impunity, Israel no longer needs to pretend. Gone are the days of Israel paying even lip service to the ‘peace process’, or pretending that it does not intend to annex and colonize even more occupied Palestinian land.

Israel’s fig leaves are rapidly dropping, alienating even longtime supporters. The silver lining, perhaps, is that it is revealing the cracks and decay in long maintained myths surrounding the colonization of Palestine.

Thanks to the meticulous scholarship, documentation and investigative research carried out by Palestinians and others, many myths have already been dispelled, such as the claim that Palestine was an empty, barren land upon the arrival of the Zionist settlers. Today, no impartial historian can seriously argue such a claim. Yet for the longest time, this falsehood stood tall and fast, it was the accepted ‘truth’ for millions, a crucial baseline for the Israeli narrative. Many more myths still remain in the mainstream to this day.

Unable to find hope looking forward, it is not surprising that, as a form of escapism perhaps, many look back and imagine what could have been. ‘If only something had been done earlier’, they wistfully muse, ‘the two state solution could have been a reality’. Predictably, this is often when the blame game begins.

One of the most salient examples of this, especially around Nakba day discourse, is when Palestinians are held to blame for everything by rejecting partition. To paraphrase, the argument goes:

“Had the Palestinians only accepted the UN partition plan in 1947, they too could have been celebrating their independence alongside Israel.”

This, I argue, is a classic case of victim blaming, and yet another ahistorical myth in need of correcting.

Zionism and colonialism

Sustaining this argument requires some glaring lies of omission and manipulation of facts. I believe it is important to scrutinize this claim, and this can only be done by conveying a historically accurate depiction of the debates and context surrounding partition.

Before we can talk about partition, however, we need to talk about those demanding partition. Based on the Israeli narrative, this would be “the Jewish people”. This is a dishonest assertion and is often uncritically accepted by many.

This line of thought conflates the Jewish people with political Zionism, an ideology finding its origins in Europe in the late 1800s. At the time, the Jewish people were largely uninterested in Zionism. As a matter of fact many groups were fiercely anti-Zionist. The attempt to conflate the two is an attempt to give legitimacy to self-professed settlers from Europe, and portray any criticism of the Zionist project as inherently antisemitic.

Yet in the early days, the Zionist movement was astonishingly honest about its existence as a form of colonialism. The founding fathers of Zionism, such as Herzl, Nordau, Ussishkin and Jabotinsky –among others- employed the same colonial tropes and tactics used by Europeans to legitimize their imperialism. Not only was Zionism colonialism in practice, but Zionists openly referred to it as such; for example, Herzl sought counsel from Cecil Rhodes on how best to proceed with the process of colonization, describing Zionism as ‘something colonial’. To drive this point even further, the first Zionist bank established was named the ‘Jewish Colonial Trust’ and the whole endeavor was supported by the ‘Palestine Jewish Colonization Association’ and the ‘Jewish Agency Colonization Department’.

At the end of the day it was a group of European settlers claiming an already inhabited land for an exclusivist ethnic state, while planning to ‘spirit the penniless population across the border’ through various means. Modern attempts to retroactively whitewash Zionism, and portray it merely as a movement for self determination, cannot escape these facts.

Partition and its discontents

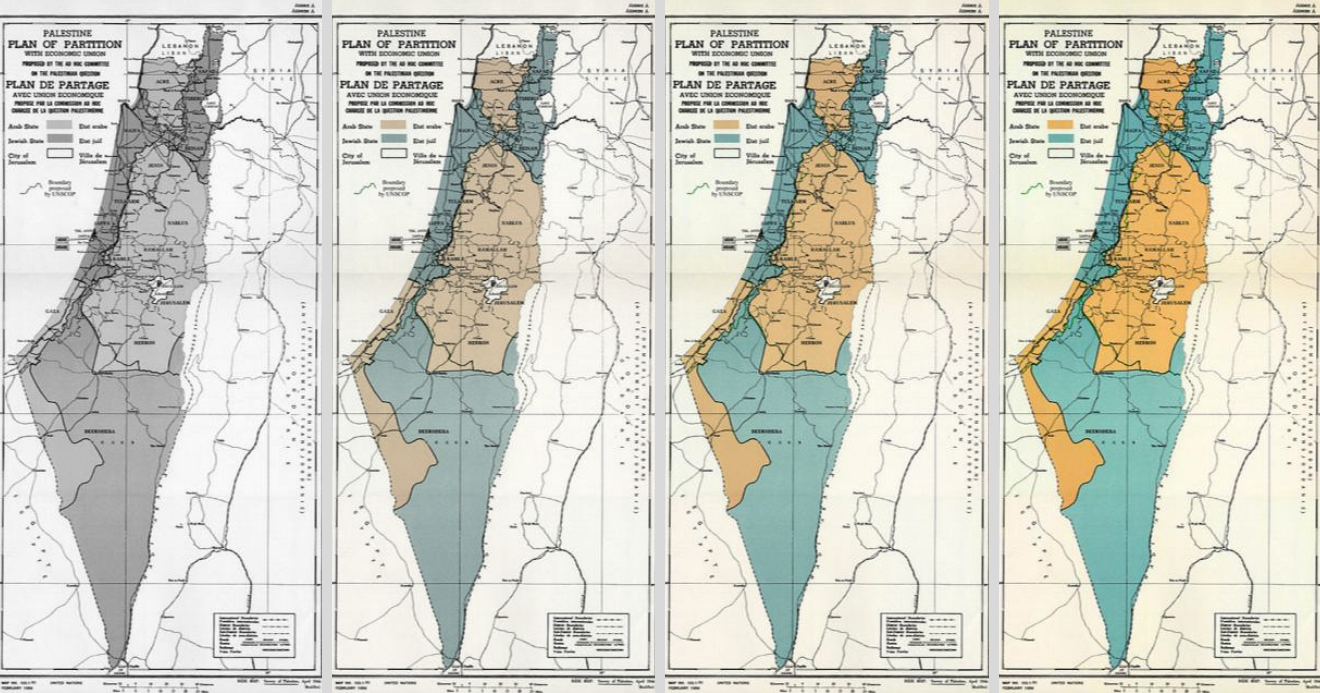

When partition is brought up in the historical sense, it is not surprising that most tend to think of the 1947 UNGA resolution. However, this was not the first partition scheme to be presented. In 1919, for example, the World Zionist Organization put forward a ‘partition’ plan, which included all of historical Palestine, parts of Lebanon, Syria and Transjordan. At the time, the Jewish population of this proposed state would not have even reached 1-2% of the total population.

Naturally, such a proposal did not see the light of day, but it is an indication of the entitlement of the Zionist movement in wanting to establish an ethnic state in an area where they were so utterly outnumbered. To put this into context, even after waves of Jewish immigration to Palestine, and a much smaller area allocated to the Jewish state in the 1947 partition plan, the proposed Jewish state would have had a Jewish majority of only 60%. As even on the eve of the Nakba, the Jewish population in mandatory Palestine was barely a third.

If we consider that most of this population arrived during the 4th and 5th Aliyot (Between 1924-1939), then the majority of those demanding partition of the land had barely been living there for 20 years at the most. To make matters worse, the UN partition plan allotted approximately 56% of the land of mandatory Palestine to the Jewish state.

Why, then, were Palestinians expected to agree to give away most of their land to a minority of recently arrived settlers? Why is the rejection of such a ridiculously unjust proposal framed as irrational or hateful?

Jabotinsky understood clearly what establishing Israel meant for the natives; he did not mince words, in his 1923 essay The Iron Wall he wrote that ‘Every native population in the world resists colonists as long as it has the slightest hope of being able to rid itself of the danger of being colonised’.

What was being asked of Palestinians was nothing short of rubber-stamping their own colonization with approval. Nobody should be expected to agree to that.

The limits of Zionist aspirations

Yet for some, this is not seen as convincing reasoning for the rejection of partition. They acknowledge the obscene injustice of what was being asked of Palestinians, yet they argue that due to the historical persecution of the Jewish people, and fresh off the heels of the Holocaust, creating a Jewish state at the expense of Palestinians was a historic necessity.

While such justifications serve mainly to assuage guilt, I argue that there is also a practical reason for why accepting or rejecting partition was irrelevant to the grand scheme of Zionist colonization of Palestine.

It is often brought up how the Yishuv agreed to the 1947 partition plan, showing good will and a readiness to coexist and live with their Palestinian neighbors. While this may seem true on the surface, a cursory glance at internal Yishuv meetings paints an entirely different picture. Partition as a concept was entirely rejected, and any acceptance in public was tactical in order for the newly created Jewish state to gather its strength before expanding.

While addressing the Zionist Executive, Ben Gurion reemphasized that any acceptance of partition would be tactical and temporary:

After the formation of a large army in the wake of the establishment of the state, we will abolish partition and expand to the whole of Palestine.

This was not a one-time occurrence, and neither was it only espoused by Ben Gurion. Internal debates and letters illustrate this time and time again. Even in letters to his family, Ben Gurion wrote that “A Jewish state is not the end but the beginning” detailing that settling the rest of Palestine depended on creating an “elite army”. As a matter of fact, he was quite explicit: “I don’t regard a state in part of Palestine as the final aim of Zionism, but as a mean toward that aim.”

Chaim Weizmann expected that “partition might be only a temporary arrangement for the next twenty to twenty-five years”.

So even ignoring the moral question of requiring the natives to formally green-light their own colonization, had the Palestinians agreed to partition they most likely still would not have had an independent state today. Despite what was announced in public, internal Zionist discussions make it abundantly clear that this would have never been allowed.

Partition today remains as immoral as it was when first presented, a band-aid solution and a cure for a symptom which overlooks the root cause. Any settlement that is achieved without justice or accountability merely buries the issues in exchange for short-lived quiet; but no matter how long it takes, silenced and ignored grievances will resurface. This becomes exceedingly clear when observing the situation of our brothers and sisters in South Africa today.

The impending demise of the Oslo accords can serve as a catalyst to challenge the fixation on the pre-1967 war borders. Reducing the question of Palestine to partition and occupation overlooks crucial components of the struggle. Many may prefer to ignore said components; however, if true peace and justice are our goal, then they must be discussed and confronted. We must start from the beginning and reject any urges to whitewash history. Only with full accountability for the past can we work towards a vision for the land between the river and the sea.