Languages in Gender Transition: English, French, Spanish, and Arabic

Allison

Washington, Medium, March 19. 2018

I

remember the kerfuffle in the 1970s, as Second Wave feminism was introducing Ms

to replace Mrs/Miss and was starting to dismantle the generic ‘he’ and ‘man’.

Oh, the outrage. But that shift in the English language turns out to have been

relatively straight forward. We face bigger challenges.

remember the kerfuffle in the 1970s, as Second Wave feminism was introducing Ms

to replace Mrs/Miss and was starting to dismantle the generic ‘he’ and ‘man’.

Oh, the outrage. But that shift in the English language turns out to have been

relatively straight forward. We face bigger challenges.

|

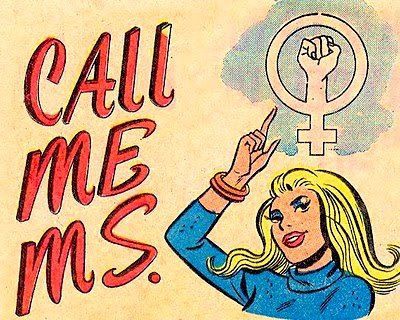

| This image was originally intended to be ironic; the 1975 girls’ comic from which it comes was part of the broad cultural backlash against ‘Women’s Lib’. It portrayed sexual harassment as a necessary and inevitable prelude to romance. Yep, that’s the context in which I came of age. |

You will be

familiar with current struggles to de-gender English so as to eliminate gender

bias and misgendering. Efforts include increasing acceptance of the singular they*

and such constructs as the Mx title (pronounced ‘məks’ with a schwa

[ə]; roughly ‘mix’, if you reduce the ‘i’).

In the

midst of the current pronoun argument, it is easy to forget how remarkably

gender-free the English language is (why is that?), and how little we

anglophones need to deal with, compared to speakers of most other languages.

Most languages are terribly concerned with the masculinity vs femininity of

those being discussed (why is that?), and some, as in the case of Arabic, are

so entrenched in gender that the sex of everyone involved must be sorted before

even the most basic conversation can commence.

midst of the current pronoun argument, it is easy to forget how remarkably

gender-free the English language is (why is that?), and how little we

anglophones need to deal with, compared to speakers of most other languages.

Most languages are terribly concerned with the masculinity vs femininity of

those being discussed (why is that?), and some, as in the case of Arabic, are

so entrenched in gender that the sex of everyone involved must be sorted before

even the most basic conversation can commence.

I grew up

speaking French, English, and Spanish†, and have recently relocated to Cairo,

where I am presently wrestling with Egyptian Arabic.

speaking French, English, and Spanish†, and have recently relocated to Cairo,

where I am presently wrestling with Egyptian Arabic.

In

English one must navigate gendered forms of address (Mr/Ms, sir/ma’am) and

pronouns in the third person (s/he), but romance languages (French, Spanish,

Catalan, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian) have the added challenge of gendered

adjectives (big, happy, American), and these can be self-referential. I happen

to be transgender, and when I was transitioning French and Spanish presented

linguistic minefields of gender as I struggled to switch years of habit,

leading to hesitant speech and occasional self-misgendering and brutally

awkward incidents. With its embedded sexism, language is against you when you

transgress gender norms, but English is less hostile than most.

English one must navigate gendered forms of address (Mr/Ms, sir/ma’am) and

pronouns in the third person (s/he), but romance languages (French, Spanish,

Catalan, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian) have the added challenge of gendered

adjectives (big, happy, American), and these can be self-referential. I happen

to be transgender, and when I was transitioning French and Spanish presented

linguistic minefields of gender as I struggled to switch years of habit,

leading to hesitant speech and occasional self-misgendering and brutally

awkward incidents. With its embedded sexism, language is against you when you

transgress gender norms, but English is less hostile than most.

In

French, for example, English’s blessedly gender-neutral adjectives in ‘I am

French’ and ‘I am happy’ become—

French, for example, English’s blessedly gender-neutral adjectives in ‘I am

French’ and ‘I am happy’ become—

« Je

suis Français / Française. »

suis Français / Française. »

and

« Je

suis heureux / heureuse. »

suis heureux / heureuse. »

Efforts

to make French more gender friendly lead to such peculiar written constructs as

Français.e and heureu.x.se.

to make French more gender friendly lead to such peculiar written constructs as

Français.e and heureu.x.se.

For a

Spanish example, take English’s ‘I’m delighted’ and ‘I am Hispanic’, and you

have—

Spanish example, take English’s ‘I’m delighted’ and ‘I am Hispanic’, and you

have—

“Encantado

/ encantada.”

/ encantada.”

and

“Soy

Latino / Latina.”

Latino / Latina.”

along

with new de-gendered written constructs like encantadx and Latinx.

with new de-gendered written constructs like encantadx and Latinx.

No one

has any clue how one might pronounce encantadx or heureu.x.se, so speech (where

it really matters, after all) remains gender-locked.

has any clue how one might pronounce encantadx or heureu.x.se, so speech (where

it really matters, after all) remains gender-locked.

But

French and Spanish are nothing to Arabic. OMG.

French and Spanish are nothing to Arabic. OMG.

To the

gender trouble of forms of address, third person pronouns, and adjectives, let

us add second person pronouns, verbs, and adverbs. Take the verb understand, in

French comprendre, and we are thankfully innocent of gender:

gender trouble of forms of address, third person pronouns, and adjectives, let

us add second person pronouns, verbs, and adverbs. Take the verb understand, in

French comprendre, and we are thankfully innocent of gender:

‘I

understand.’

understand.’

‘You

understand.’

understand.’

« Je

comprends. »

comprends. »

« Vous

comprenez. »

comprenez. »

A little

extra conjugation in French, but no biggie.

extra conjugation in French, but no biggie.

Now,

Egyptian Arabic—

Egyptian Arabic—

“Ana

bafham.”

bafham.”

So far so

good, no gender there, in the first person. But go to the second person, and—

good, no gender there, in the first person. But go to the second person, and—

“Inta

bdifham.” [Masculine you, masculine understand.]

bdifham.” [Masculine you, masculine understand.]

and

“Inti

bdifhami.” [Feminine you, feminine understand.]

bdifhami.” [Feminine you, feminine understand.]

You’d be

forgiven for thinking that understanding is a different thing for each gender.

That actions and events differ by gender, as do their verbs. Language creates

thought creates culture creates language. We think and emote within the

channels our language provides, and we’re unaware of this unless we think for

extended periods in more than one. I have long been aware that I feel

differently about important things depending on whether I’m living in French or

in English. I expect I shall feel differently still in Arabic. If I can learn

the damned thing. Back to the grammar…

forgiven for thinking that understanding is a different thing for each gender.

That actions and events differ by gender, as do their verbs. Language creates

thought creates culture creates language. We think and emote within the

channels our language provides, and we’re unaware of this unless we think for

extended periods in more than one. I have long been aware that I feel

differently about important things depending on whether I’m living in French or

in English. I expect I shall feel differently still in Arabic. If I can learn

the damned thing. Back to the grammar…

Lest you

think the first person (ana) has escaped gendering, uh, not really; not if you

want to use a verb for some reason. Here, with the verb ‘to be’, is ‘How are

you?’ / ‘I am well’:

think the first person (ana) has escaped gendering, uh, not really; not if you

want to use a verb for some reason. Here, with the verb ‘to be’, is ‘How are

you?’ / ‘I am well’:

To a man,

who then responds, it’s—

who then responds, it’s—

“Izeyak?”

“Ana qwayis.”

And with

a woman—

a woman—

“Izeyik?”

“Ana

qwayissa.”

qwayissa.”

Aaand…there’s

your gendered verb and adverb, yep. Both people’s gender must be stated as

either male or female. No ambiguity allowed. This simple exchange acts as an

assignment of binary and unambiguous gender by one person upon another, and the

other’s confirmation of that assignment.

your gendered verb and adverb, yep. Both people’s gender must be stated as

either male or female. No ambiguity allowed. This simple exchange acts as an

assignment of binary and unambiguous gender by one person upon another, and the

other’s confirmation of that assignment.

As a

practical matter, this means keeping track of gender on many more word-types,

with the corresponding huge increase in vocabulary and confusion for the

learner.

practical matter, this means keeping track of gender on many more word-types,

with the corresponding huge increase in vocabulary and confusion for the

learner.

As a

cultural matter, Arabic is rigidly gender-locked. Adding to the pressure on a

foreigner struggling to communicate, misgendering someone in this culture (say,

with a stray ‘-ik’ instead of ‘-ak’) is deeply offensive; deployed as the worst

possible insult. Uh-huh.

cultural matter, Arabic is rigidly gender-locked. Adding to the pressure on a

foreigner struggling to communicate, misgendering someone in this culture (say,

with a stray ‘-ik’ instead of ‘-ak’) is deeply offensive; deployed as the worst

possible insult. Uh-huh.

And pity

anyone who cannot or would not present as clearly male or female. You’re just

screwed.

anyone who cannot or would not present as clearly male or female. You’re just

screwed.

English

seems to be well on the way to de-gendering itself; we already have

sometimes-awkward but workable solutions. I’ve no idea what to do with the

gender embedded in French and Spanish, but at least some people are motivated

and experimenting, and perhaps something will sort in time.

seems to be well on the way to de-gendering itself; we already have

sometimes-awkward but workable solutions. I’ve no idea what to do with the

gender embedded in French and Spanish, but at least some people are motivated

and experimenting, and perhaps something will sort in time.

I’m not

holding my breath for Arabic. In a language and culture where genderless

address is impossible, misgendering is deeply offensive, and gender

presentation is heavily policed and any ambiguity in presentation is met with

outright abuse‡, I expect that binary gender bias is here for the long-haul.

Today, some in the more progressive educated younger generation of Arabic-speaking

people will sometimes use English amongst themselves. If it’s not their native

language, at least they can say what they mean with respect. It’s a linguistic

shame, really, that they have to move outside their native tongue to express

themselves, but maybe that’s the way forward.

holding my breath for Arabic. In a language and culture where genderless

address is impossible, misgendering is deeply offensive, and gender

presentation is heavily policed and any ambiguity in presentation is met with

outright abuse‡, I expect that binary gender bias is here for the long-haul.

Today, some in the more progressive educated younger generation of Arabic-speaking

people will sometimes use English amongst themselves. If it’s not their native

language, at least they can say what they mean with respect. It’s a linguistic

shame, really, that they have to move outside their native tongue to express

themselves, but maybe that’s the way forward.

In the

meantime, I have a lot of verb forms to learn…

meantime, I have a lot of verb forms to learn…

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* And by

the way, obviously it should be ‘they is’, not ‘they are’. (Just stirring the

pot, here…)

the way, obviously it should be ‘they is’, not ‘they are’. (Just stirring the

pot, here…)

† More

accurately, I was introduced to Spanish at a young age, but most of my

vocabulary was acquired during ten years spent in Latin America as an adult.

accurately, I was introduced to Spanish at a young age, but most of my

vocabulary was acquired during ten years spent in Latin America as an adult.

‡ In

Egypt, showing hair cut ‘too short’ is enough to get a woman subjected to

public abuse, I have yet to see a man with hair below the ear, and I rarely see

someone I can’t easily identify as either male or female at 200 metres

distance.

Egypt, showing hair cut ‘too short’ is enough to get a woman subjected to

public abuse, I have yet to see a man with hair below the ear, and I rarely see

someone I can’t easily identify as either male or female at 200 metres

distance.