Shuar tribe face government in Amazon mining protests

December 29, 2016

Ecuador’s Shuar say mining project in Cordillera del Condor threatens their livelihood and encroaches upon their land.

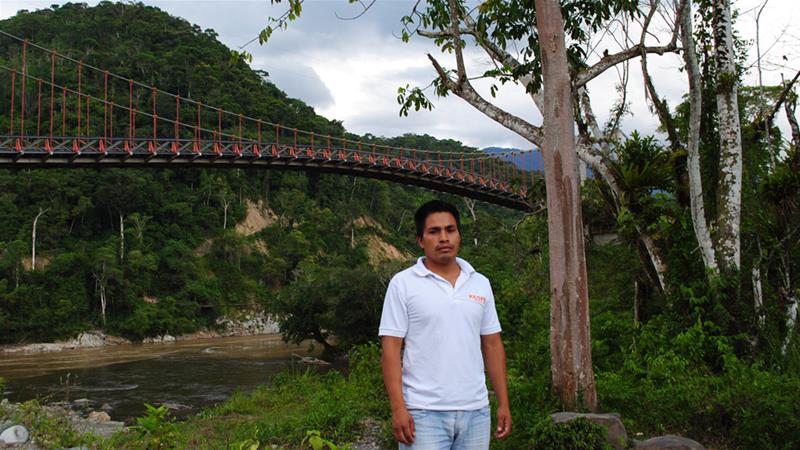

Native Shuar activists and leaders say they are being targeted by the government for their opposition to the mining project [Alfredo Salgado/Al Jazeera]

Morona-Santiago, Ecuador – The death of a police officer during a standoff between military and indigenous Shuar people in a takeover attempt of a mining camp in Ecuador’s southern Amazon on December 14, catalysed a government mobilisation of armed forces in the region.

With a 30-day state of exception imposed across the entire Amazonian province of Morona Santiago, the government has reportedly mobilised up to 1,000 military and police personnel to protect the mining camp and hunt down what top officials have called an “illegally armed group” that they say does not represent the Shuar nation.

Under the emergency decree, which has suspended rights such as freedom of expression and the inviolability of the home, reportedly five Indigenous Shuar and four mestizo men have been arrested and sentenced to 90-day preventive incarceration.

Human rights observers and Indigenous leaders have reported the arbitrary use of tanks, helicopters, rifle blasts and house raids by the military in what they say is an unprecedented “witch-hunt” against those threatening mega-mining projects in the Amazon.

Most notably, the imprisonment of Agustin Wachapa, President of the Interprovincial Federation of Shuar Peoples, and the closure of environmental activist group Accion Ecologica for allegedly “inciting public disorder” in their calls for solidarity protests with the Shuar people, have attracted condemnation from rights groups.

Fighting to keep ancestral territory mining-free

Shortly after a SWAT team was seen patrolling the streets of Gualaquiza, a small town two hours south from the conflict hotspot, Raul Ankuash expressed his fear. “I have to disappear, they are looking for me,” he said.

Upon receiving information that he appears on the government’s blacklist, Ankuash pondered the same strategy as other fellow Shuar leaders who have gone into hiding following the military manhunt.

The Ministry of Interior has said it will pay up to $50,000 for any verifiable leads that can identify those responsible for the police officer’s death.

Among the military’s most wanted are the 40 to 60 people who make up the “militant” base of Indigenous Shuar according to Raul, whose father Domingo Ankuash is one of the most vocal Shuar leaders in the anti-mining movement in the Amazon.

This base coordinated the recent attack that resulted in the casualty at the mining camp in Nankintz, territory where Chinese company EcuaCobres SA (EXSA) has begun advanced exploration for gold and copper extraction.

Shuar leaders and government officials have blamed each other for the death, but neither have offered concrete evidence to sustain their claim.

When asked about the evidence, an Interior Ministry spokesperson told Al Jazeera the case was still under investigation.

Conflicts over the mining camp have arisen over the 41,000 hectares of land conceded to EXSA across the uniquely biodiverse Cordillera del Condor, a mountain range connecting Ecuador’s southern Andes with the Amazon. Of these concessions nearly 50 percent are on ancestral Shuar territory .

“These concessions are completely illegal and unconstitutional,” Ankuash said, “there was no consultation with the Shuar communities during these concessions, a violation of the constitution and a total abuse of power by the government.”

According to Shuar rights lawyer Tarquino Cajamarca, the government holds no obligation to consult landowners for concessions since technically they own the land, but not the subsoil.

“A concession is a property title over a subsoil for mining operations,” Cajamarca told Al Jazeera, “and it is the state that owns the subsoil, as well as the rivers, the mountains, etc.”

In an email correspondence with Al Jazeera, ExplorCobres SA countered the allegation that they have not engaged affected community members in their project, saying it “counts with all of the support of the communities in its zone of influence.”

“We cannot go back when the majority of the people in the area are waiting for us with open arms in the face of a group that is opposed to progress,” their statement added.

EXSA, has a history of conflict since settling up its mining camp in Nankintz, from where it will exploit the subsoil.

Nankintz used to be communal Shuar territory but ended in the company’s hands as private property because of agrarian policies in the 1990s, when the state started selling any land thta had no houses or cultivation to mestizo settlers.

The incursion of the foreign mining company, then Canadian, was met with widespread opposition from Shuar and mestizo farmers. In a show of unity together with Accion Ecologica, they succeeded in expelling EXSA from Nankintz in 2006.

To keep the area mining-free, a group of 32 Shuar settled on the 90 hectares of land until they were forcibly evicted in August this year by military troops for “illegally occupying land” belonging to EXSA.

“They want to get into Warints, Banderas, Kuangos – all Shuar communities – to disband the people and carry out mining there,” Ankwash said, “Nankintz was there to defend these communities because it is from there that you can access them.”

If fully operational, EXSA’s Panantza-San Carlos Project would be the world’s second largest copper mine and generate an estimated $1.2bn in annual profits.

Paying with lives

Despite leading the bold and innovative concept of the Rights of Nature in its 2008 Constitution, President Rafael Correa defended the new mining projects, arguing that “the most important thing about nature continues to be the human being and the primary ethical and moral duty is to defeat poverty.”

Correa’s fully fledged military operation to protect mega-mining on the one hand, and the steadfastness among some Shuar to defend their territory on the other, make peaceful resolution of the conflict an unlikely possibility.

Ankuash says he is determined to continue defending his territory, but admits young Shuar people like him are afraid.

He mentions the death of Jose Isidro Tendetza in December 2014, a Shuar leader who is speculated to have been assassinated for opposing the Mirador Project, Ecuador’s first large scale copper mine in neighbouring province Zamora Chinchipe.

To proceed with the opencast pit mining operation there, up to 16 families in the rural parish of Tundayme were forcibly evicted from their homes and land a year later.

Two other Shuar men have died in mining-related circumstances: Bosco Wisum in 2009 and Freddy Taish in 2013 .

“This is the beginning of a fight to exterminate the Shuar people because we are the only nation that have strongly defended our territory,” Ankuash said. “If they have to exterminate us, they can do it. Maybe then they can go on with the mining. But until then we will continue to defend the land they have conceded to the mining companies.”

Lying only 20 minutes from the EXSA mining camp, Panantza is the nearest village and a strategic military outpost [Alfredo Salgado/Al Jazeera]

Panantza: a farmers village under military siege

Sitting between heavy rain clouds and the luscious green mountains that make up the Cordillera del Condor, the small agrarian village of Panantza has been under military siege since the state of exception was issued.

Its location only 20 minutes from the EXSA mining camp makes Panantza its nearest village and consequently a strategic military outpost.

The area remained largely inaccessible to the media for more than a week, during which Regional Foundation for Human Rights Advisory reported cases of property destruction, abuse, arbitrary raids and arrests at the hands of the military.

A woman in her early 20s, who spoke in anonymity, alleges that the military burned down her family’s farm house because they suspected Shuar fighters were using it as a base during their take-over attempt.

“We were two families, 12 people, who lived there. We lost everything in the fire. We don’t even have our clothes,” the Panantza native told Al Jazeera.

“Then they raided my father’s house, broke the windows and turned everything upside down because they thought we were hiding weapons to help the Shuar.”

Any suspicion or evidence hinting at an anti-extractivist position has meant trouble in a village where farmers fear the open-cast mining project will contaminate their rivers and destroy the cloud forests they depend on for agriculture and cattle.

“A lot of us are afraid that with the mine there will be nothing left for us campesinos. Some people agree because they promised work,” an 80-year-old Panantza local told Al Jazeera in anonymity.

“But look at Tundayme, there are no jobs there. They gave them to the Chinese. And the rivers are contaminated so no one can farm there any more.”

“There’s no way to protest against the mine because they will just send you to jail. Look, they have put up cameras everywhere and the police come and go,” he added.

President and Vice-President of Panantza’s parish board, Danny Marin and Milton Reinoso, have represented these concerns and long been vocal opponents of the mining project.

They were also the first ones to be taken from their homes during the military operation and handed down a 90-day preventive incarceration sentence for attempted murder against the police.

“First they want to sow fear so that no one rises up,” Severino Sharupi, leader of territories and natural resources of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, told Al Jazeera.

“Then they want to imprison some of the main spokespersons of the resistance so that there cannot be any opposition in the territory. This is why they arrested Danny Marin, who has been one of the key mestizo figures in the resistance. The state needs to have an authority there that gives permission to the company and allows them in,” Sharupi added.

The Interior Ministry has denied any restriction on freedom of expression on behalf of the military.

“People in Morona Santiago are free to publicly disclose their stance in favour or against the mining industry,” Maria Cristina Zuniga, director of the ministry’s communication department, told Al Jazeera.

“If people are afraid to talk, it is rather due to the tense environment following the criminal attacks of December 14,” Zuniga added.

The Interior Ministry further countered any allegations of unlawful misconduct on behalf of security forces in the region, adding that in fact “campesinos are showing their gratitude for the deployment of police units that are keeping them safe” from the sought-after armed group.

Solidarity protests with the Shuar struggle have flared up across the country [Kato Muñoz/Al Jazeera]

Solidarity protests

Since the escalation of the conflict in Morona-Santiago, solidarity protests with the Shuar struggle have flared up across the country.

In Quito, environmentalist activists and national Indigenous leaders have held joint demonstrations in front of the presidential palace and improvised assemblies to map out further resistance strategies.

“We are building new alliances between the city and the countryside, mestizos and Indigenous. It is events like these that help activate a new consciousness and build a larger platform,” Luis Corral, a leading environmental activist, told Al Jazeera.

According to Corral, this represents a significant shift from the Yasunidos initiative, an urban youth movement that tried but eventually failed to keep the Correa government from drilling oil in Yasuni, one of the most biodiverse rainforests in the Amazon.

“There was a lot of confusion among the Yasunidos, they depoliticised the issue and their discourse turned very mild, lax. There were fights with Indigenous leaders because they didn’t build enough with the Indigenous movement,” Corral said.

The solidarity mobilisations have spread to other cities such as Latacunga and Cuenca where protesters linked the Shuar struggle to local concerns over ongoing conflicts with large mining projects and water privatisation.

The protest wave comes in the aftermath of an “Indigenous uprising” that shook the country in the summer of 2015, when a myriad of Indigenous struggles over largescale resource extraction projects across the Andes and Amazon took to the streets to demand the resignation of President Correa.