Parliament for the people: the architect rebuilding Burkina Faso’s political heart

October 4, 2016

Award-winning Francis Kéré is taking the lead in replacing the parliament set ablaze in his country’s 2014 revolution

Francis Kéré first started building things back in his home town of Gando in eastern Burkina Faso. Sent with other children to keep an eye on the livestock, Kéré and his friends would cut down tree branches and build a structure on the floor to sit on.

“Perhaps we did it in the spirit of creating a house, or perhaps simply to protect us from the sun, but in any case, we did it quite meticulously,” the architect remembers.

Kéré grew up in an environment where, with each rainy season, houses built with mud bricks melted and disappeared. When he began designing buildings, it was with the clear idea of “doing something sustainable” for his village.

Now 51, Kéré has moved on to designing sustainable structures for his country: he is steering plans for the new Burkinabé parliament to replace the one set on fire during the 2014 revolution when citizens thwarted President Blaise Compaoré’s attempts to stay in power and quashed an attempted military coup launched a year later.

It is the first time the country has been free of dictatorial rule for more than three decades, and Kéré is marking the occasion by designing a structure that will “scale up the village dynamics while bolstering national identity”.

At the Venice Biennale this year, which united architects under the theme Reporting from the Front, Kéré presented his project as an answer to the question: “What kind of parliament should be built for a people who have chosen to throw out their rulers?”

The stakes for a new building are high, Kéré says. “It’s a very delicate situation. I would like to open the project to as many contributors as possible, from artists to professional architects.”

According to Giovanni Quattrocolo, an architect who has been working in Ouagadougou for two years, the government was on the verge of launching a contest for the reconstruction project when Kéré intervened and insisted on starting an open discussion with local architects instead.

Though no opening date has yet been announced, in Ouagadougou a rumour is spreading that Kéré plans to keep the parliament’s burnt door in place, a reminder for MPs entering every morning of the power of the people they represent.

Francis Kéré’s Lycée Schorge secondary school in Koudougou, Burkina Faso. Photograph: Sophie Garcia | hanslucas

Burkina/Bauhaus

One of his models for the new parliament is Louis Kahn’s National Assembly building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, completed in 1982. Along with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the German master known for his rationalism and modularity, Kahn has had a big influence on Kéré designs.

Kéré was exposed to the Bauhaus style after winning a scholarship in Germany. He went on to study architecture in Berlin when he was in his early 30s. There, Kéré created an association, Schulbausteine für Gando, to raise funds to build a school in his home village.

Realised in 2001 with a tight budget of $30,000 (then about £20,000), the school became Kéré first building project. In the absence of heavy and costly equipment such as cranes, Kéré was forced to be creative.

He used perforated clay and light steel bars for the roof, making the natural ventilation a central part of the structure. The school earned him the prestigious Aga Khan award “for his architectonic clarity and transformation value”.

“Honestly, without the Aga Khan prize, my work would never have been discovered,” Kéré says. “The visibility and recognition attached to it bring a lot of energy, and of course the money enabled me to pursue my research and projects.”

Distinctive traits of Kéré’s work can be traced back to this first building in Gando: first, the use of local materials. “Since the French [colonial] rule, the old system is still in our heads,” says Kéré. “People were at first surprised that my plan was to build the school in clay, not in cement or glass.”

Community is also at the centre of Kéré’s work. “Everybody in the village was a part of this. This is how we build things in rural areas. It enables us to integrate each individual’s knowhow into the final project.”

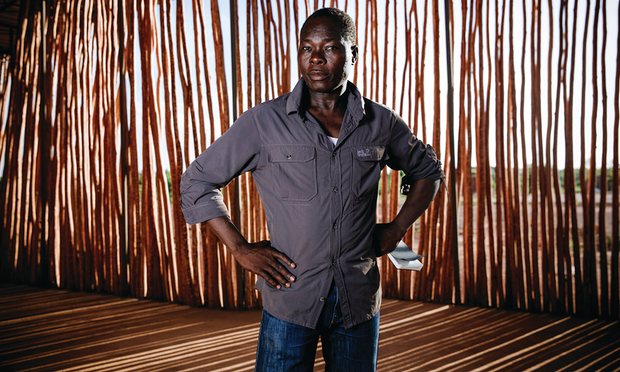

Kéré sketching during a lunch break with colleagues in Koudougou, Burkina Faso. Photograph: Sophie Garcia | hanslucas

This is, however, is at odds with the main building trend in west Africa, where there is a voracious appetite for cement. “It’s not so much the material which is a problem here,” says Kéré. “It’s the lack of reflection. Project developers don’t think quality, they think quantity. Replica, not authenticity. Their production boils down to cheap copies of foreign influence, not at all in tune with the climatic conditions here.”

With the help of the Aga Khan Foundation, the architect also worked on two major projects in Mali to mark 50 years of independence in 2010: a national park in the capital, Bamako, and the Centre for Earth Architecture in Mopti.

“I was surprised to see what you can do when you work with partners with a long-term vision,” says Kéré. “They said: ‘We want a green lung for Bamako’, and we created something impeccable.”

At the time, Mali was tackling an Islamist insurgency in the north, and terror attacks were becoming increasingly frequent. Kéré said that, like in Burkina Faso, he was inspired by what architecture can achieve in times of unrest, by “creating space for future generations without destroying the environment”.