Our Article about the Ruling Woman Devlet Hatun of Iran on MintPress

Great Women In Islamic History:

Devlet Hatun Of Iran

Follow @promosaik_ @promosaik_

Castle in Hurremabad, seat of government in Lesser Luristan

(part of

modern-day Iran) in the days of Devlet Hatun. (Wikimedia / Adowus)

Other selections from this series: Introduction: A Forgotten Study Of Female Political Power In Muslim History, Türkan Hatun of Iran, Padishah Hatun of Iran and Ebesh Hatun Of Iran.

Devlet Hatun of the Hurshitoğulları State in Lesser Luristan

Between the sixth and ninth centuries of the Hegira, two states were

founded in the southwest region of Iran which was occupied by the Lur

tribes. Of these one was the “Great Lurlu,” also known as “Hezarespî” or

“Fazlûye.” The other was the kingdom of “Lesser Luristan” or “Beni

Hurshit” (translation: the sons of Hurshit).

Since Bahriye Üçok’s work is concerned only with the latter, only

Lesser Luristan will be discussed in this chapter about Devlet Hatun.

A brief history of Lesser Luristan

The rulers of the state of Lesser Luristan were descended from the

Jangruî tribe. It was originally called “Hurshitoqullari” and continued

to be known by this name until the sixteenth century, after Muhammed

Hurshid who was a former vizier of the Lurlus and who was the first

ruler from this family. The name of Lesser Luristan, which was the area

where it was situated, was not given to the Hurshitoqullan state until

after the sixteenth century.

The founding of this state, the capital of which was Hurremabad,

occurred roughly speaking in about 591/1195. Unfortunately, the order

and dates of succession of the rulers who held power in this country for

about 400 years are not accurately known.

İzzüddîn Kürshasb, who was the fourth ruler, was followed by Halil;

when Halil died in 1242

Mes’ud, who succeeded him, was not accepted as

sovereign by the Caliphate at Baghdad. Accordingly, Mes’ud appealed to

the Mongol, who put an army at his command. In this way, he joined in

the Baghdad campaign (1258) and obtained a large share of loot.

In 1260, Mes’ud died and a fierce struggle for succession took place

between his sons Jelâlüddîn and Nâsırüddîn. The Mongols made this a

pretext for interference and Abaka put an end to the dispute by choosing

their uncle Halil’s son Tajüddîn Shah as sultan.

Tajüddîn ruled for seventeen years, after which the sixth ruler

Mes’ud’s other two sons, Feleküddîn Hasan and İzzüddîn Hüseyin (1268)

commenced to share sovereignty in Lesser Luristan. At first these two

brothers managed the areas which had been allotted to them extremely

well, but later İzzüddîn Hüseyin began to behave with cruelty, upon

which in 1292 Keyhatu removed them both and replaced them on the throne

with Jemalüddîn Hızır. But for this he was obliged to call upon the

Mongol army for help.

Later İzzüddîn Hüseyin’s son İzzüddîn Muhammed, famed for his good

looks, came to the throne at an early age. However his cousin Bedrüddîn

Mes’ud emerged as a rival and tried to obstruct him; indeed Bedrüddîn

obtained permission from Sultan Oljaytu to take possession of the Dilâr

region, but a short while later Izzüddîn Muhammed’s tax rights over all

these parts were recognized.

Owing to his services and his obedience to the Mongols, İzzüddîn

Muhammed continued to rule Lesser Luristan throughout his lifetime, in

so-called independence, and he died in 716/1316-7. In spite of the lack

of sources which give information on this subject, it appears that on

İzzüddîn Muhammed’s death he left neither a son nor yet a brother to

succeed him.

Since neither the Mongols nor the Turks, nor nations related to them

had any rules on the question of succession to the throne, it was

thought appropriate that the dead king should be succeeded by his wife

Devlet Hatun (716/1316-7), who was the daughter of Shemsüddîn, also of

this family.

Devlet on the throne

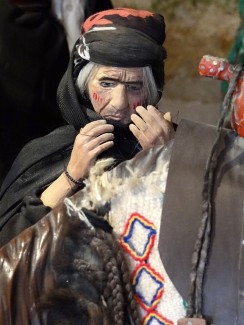

of a Lurish woman in mourning from the Ethnographic Museum inside

Falak-ol-Aflak Castle. The woman wears a black headscarf and robe, has

red makeup on her face. (Wikimedia / Adam Jones)

Devlet Hatun, who came to the throne as the 14th of the

Hurshitoqullari rulers, was unable to retain power for long. She was

not, in any case, the ruler of a completely independent state, but was

chief of a semi-independent country that owed allegiance to the powerful

Ilhan Empire.

This being the case, she could not prevent the Mongols from

interfering in the affairs of the state. The people were heartily tired

of the Mongols, but Devlet Hatun was not a strong or capable woman like

the ruler of Kirman, Türkân Hatun, or the Turkish Empress in Delhi, Raziyye Sultan. In addition, she was inclined to keep herself withdrawn and closely veiled, which made her unable to conduct affairs.

In the same year, Ebu Said Bahadır Khan came to the Ilhan throne.

Devlet Hatun, fearing that Lesser Luristan — which was extremely rich in

various types of metal — would altogether lose its independence under

Mongol pressure, obtained the approval of the Mongol council to

relinquish her rule in favour of her own brother İzzüddîn Hüseyin.

Thus, with his succession in this year the throne in Hurremabad

passed to another branch of the Hurshitoqullan. During the fourteen year

reign of İzzüddîn Hüseyin II the people experienced a time of peace and

prosperity. His son Shüjaüddîn Mahmud II, who succeeded him, was

murdered by his own men. He was succeeded in turn by his son Melik

İzzüddîn Hüseyin III, who came to the throne at the age of twelve. The

various interesting adventures during his lifetime are related at length

in “Zafernâme” (Book Of Victories).

As regards Devlet Hatun, according to the anonymous writer of

“Tarih-i İskender,” after abdicating from the throne, she married the

Greater Lurlu’s Yusuf Shah. It is impossible to obtain further

information concerning Devlet Hatun from Hamdullah Kazvinî who wrote

“Tarih-i Güzide” at the same time that all these events were taking place.

For this reason, her general attitude to events inside and outside

the country, and the story of what befell her remain obscure. However,

by relinquishing to her brother, after a brief period of rule, the

throne she had inherited from her husband, she ensured the continuation

of this little state. By preventing it from passing entirely under

foreign domination, she gained for herself an important place in its

history.

The author writes: “In the above short account it has been possible

to give a fresh example of how, even in Luristan, which was the nearest

to Arab countries in the Islamic world, the rights of sovereignty were

not withheld.” This is an important passage to show the negative

prejudice by Bahriye Üçok concerning female power in the Arabic world

because of her Kemalist world-view.

After Emîr Îzzüddîn Hüseyin III, who was a descendant of Devlet

Hatun’s, eight more rulers, the names of whom are written in the

dynastic table, succeeded one another to the throne of the

Hurshitoqullan, until finally, in 1596, the Safevîs completely conquered

Lesser Luristan, thus finally bringing its political life as a

semi-independent state to an end.