Iran Executes Hundreds of People Each Year in Its UN-Funded War on Drugs

September 23, 2016

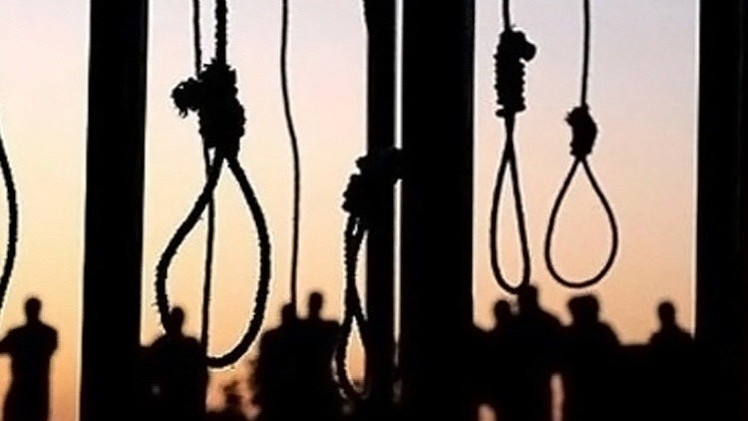

Nooses await the executions of prisoners in Iran. Photo from ICHRI and used with permission.

The latest session of the United Nations General Assembly is underway in New York City. The assembly has featured many speakers, including Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, who used the platform to address extremism in the world as well as the landmark nuclear deal with the United States and other world powers.

One thing he did not mention was the death penalty. Iran has one of the globe’s highest rates of capital punishment, a fact that if ignored inside the chamber, was highlighted by protesters outside the General Assembly.

Many of the executions are carried out in the name of Iran’s war on drugs, one of the bloodiest in the world. By Iran’s own admission, 93 per cent of the 852 reported executions between July 2013 and June 2014 were drug-related. In 2015, Iran put more than 966 individuals to death, the majority of whom appear to have faced drug-related charges.

And the United Nations is complicit. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has for years given the Islamic Republic funding for its anti-drug efforts, a partnership that has raised serious concerns about the morality and legality of the UN’s program, but will probably go unscrutinised at the General Assembly.

The UNODC was established in 1997 to address issues related to drug trafficking and abuse, among other issues related to crime and punishment. It has an estimated biennial budget of 700 million US dollars, and the majority of this funding comes from Western countries, many of whom have outlawed capital punishment in any form.

The UNODC has given Iran more than 15 million US dollars since 1998 to support operations by the country’s Anti-Narcotics Police. This is despite significant evidence that Iran’s governmental drug policies violate international law, and fall short of UNODC’s own standards.

The UK-based human rights NGO Reprieve has linked funding from the UN to at least 3,000 executions in Iran, including the execution of juvenile offenders. In 2014, for example, Iran reportedly hanged an Afghan juvenile, 15-year-old Jannat Mir, for an alleged drug offense, despite the fact that he was a minor.

See Amnesty International’s 110-page report on the execution of minors in Iran: “Growing up on Death Row”

Those who are executed are often individuals who are marginalized in Iranian society. This includes undocumented migrants and refugees from neighbouring Afghanistan, as well as ethnic and religious minorities who face disenfranchisement in Iran.

In February 2016, it was reported that Iran executed the entire adult male population of one village based on drug charges. The village, Roushanabad, is located in Balochistan, Iran’s poorest province. The population consists of ethnic and religious minorities, many of whom earn their livelihood through smuggling.

Those who face drug charges are often denied due process. A 2014 report by Ahmad Shaheed, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Iran, quoted an experienced Iranian lawyer who said that drug trials “never last more than a few minutes.” Prisoners are often denied access to counsel, and claim that confessions are forced under torture.

Human Rights Watch has accused Iran of using drug charges against political prisoners and dissidents, raising further concerns about the implications of the UNODC’s support for the country’s anti-drugs program. In 2009, Zahra Bahrami, a citizen of both the Netherlands and Iran was arrested and accused of drug trafficking – a charge she denied. She claimed her confession was extracted under duress, and activists contend that her arrest was based on her political views. She was executed in 2011.

“Iran has hanged more than a hundred so-called drug offenders this year, and the UN has responded by praising the efficiency of the Iranian drug police and lining them up a generous five-year funding deal,” said Maya Foa, strategic director of Reprieve’s death penalty team, in an interview with the Guardian in 2015.

Instead of focusing primarily on endemic problems such as poverty and a lack of opportunities for youth that foster drug abuse, Iran continues to enact draconian punishments on individuals, including publicly executing them. Observers argue these killings are a strategy by the regime to maintain political authority through intimidation, as opposed to tackling the problems of poverty and drug abuse through treatment and economic development.

From a legal perspective, there is ample evidence that Iran’s executions are a violation of international human rights law, as enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The ICCPR, to which Iran is a party, explicitly reserves capital punishment for only “the most serious crimes.” Article 6 of the ICCPR explicitly states that the death penalty cannot be imposed if a fair trial has not been granted.

In 2012, the UNODC released a position paper that appeared to critique its own involvement in Iran. The paper noted that cooperation with countries which use capital punishment “can be perceived as legitimising government actions.” It concluded that in such circumstances the organisation “may have no choice but to employ a temporary freeze or withdrawal of support.” Yet the UNODC has never publicly expressed a desire to withdraw support from its Iran program.

Iran has thus far practised its drug executions with impunity, and will likely avoid tough questions at the UN. Under current President Hassan Rouhani, who is often perceived and presented as a “moderate” politician, the rate of executions is higher than it was during the hardline presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad — a reality that seemingly betrays Rouhani’s own support base and promises of “prudence and hope.” In 2015, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Ahmad Shaheed noted that “the overall situation has worsened” with respect to human rights under Rouhani.

While the responsibility of executions and incarcerations lies foremost with the judiciary, the Rouhani administration and the appointed minister of justice, Mostafa Pourmohammadi, have remained silent and inactive on the issue.

The hypocrisy in aiding Iran is not lost on everyone. The UK, Denmark and Ireland have withdrawn funding for UNODC’s Iran program, citing human rights concerns. However, other countries including Norway and France continue to provide funding. In 2015, the UNODC renewed a five-year commitment with Iran promising an additional 20 million dollars. As the UN General Assembly convenes, the issue of funding Iran’s executions appears to have been left off the agenda.