Atheists Are Sometimes More Religious Than Christians

Sigal

Samuel, The Atlantic, May 31, 2018

A new

study shows how poorly we understand the beliefs of people who identify as

atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular.

|

|

Beyonce

performs at the Grammy Awards in Los Angeles in 2017. Lucy Nicholson / Reuters

|

Americans

are deeply religious people—and atheists are no exception. Western Europeans

are deeply secular people—and Christians are no exception.

These

twin statements are generalizations, but they capture the essence of a fascinating

finding in a new study

about Christian identity in Western Europe. By surveying almost 25,000 people

in 15 countries in the region, and comparing the results with data previously

gathered in the U.S., the Pew Research Center discovered three things.

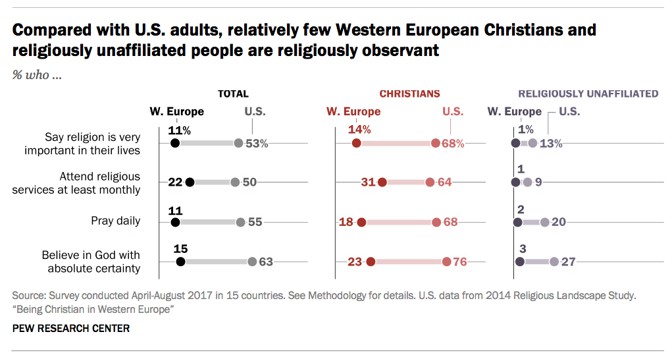

First,

researchers confirmed the widely known fact that, overall, Americans are much

more religious than Western Europeans. They gauged religious commitment using

standard questions, including “Do you believe in God with absolute certainty?”

and “Do you pray daily?”

Second,

the researchers found that American “nones”—those who identify as atheist,

agnostic, or nothing in particular—are more religious than European nones. The

notion that religiously unaffiliated people can be religious at all may seem

contradictory, but if you disaffiliate from organized religion it does not

necessarily mean you’ve sworn off belief in God, say, or prayer.

The third

finding reported in the study is by far the most striking. As it turns out,

“American ‘nones’ are as religious as—or even more religious than—Christians in

several European countries, including France, Germany, and the U.K.”

“That was

a surprise,” Neha Sahgal, the lead researcher on the study, told me. “That’s

the comparison that’s fascinating to me.” She highlighted the fact that whereas

only 23 percent of European Christians say they believe in God with absolute

certainty, 27 percent of American nones say this.

America

is a country so suffused with faith that religious attributes abound even among

the secular. Consider the rise of “atheist

churches,” which cater to Americans who have lost faith in

supernatural deities but still crave community, enjoy singing with others, and

want to think deeply about morality. It’s religion, minus all the God stuff.

This is a phenomenon spreading across the country, from the Seattle Atheist

Church to the North Texas Church of Freethought. The Oasis

Network, which brings together non-believers to sing and learn every

Sunday morning, has affiliates in nine U.S. cities.

Last

month, almost 1,000 people streamed into a church in San Francisco for an

unprecedented event billed as “Beyoncé Mass.” Most were people of color and

members of the LGBTQ community. Many were secular. They used Queen Bey’s songs,

which are replete with religious symbolism, as the basis for a communal

celebration—one that had all the trappings of a religious service. That seemed

completely fitting to some, including one reverend who said, “Beyoncé is a better

theologian than many of the pastors and priests in our church today.”

The

Catholic-themed Met Gala earlier this month was another instance of religion

commingling with secular American culture. Fashion’s biggest night of the year

saw celebrities sweeping down the red carpet dressed in papal tiaras, halos,

angel wings, and countless crucifixes. These outfits, along with the

Metropolitan Museum of Art’s accompanying exhibition, “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion

and the Catholic Imagination,” drew the ire of some Christians. But it’s

notable that so many celebrities, not to mention average Americans, embraced

the theme with gusto. It’s easier to imagine this happening in America than in,

say, staunchly secular France.

|

| Rihanna shows off her pope-inspired ensemble at the Met Gala (Eduardo Munoz / Reuters) |

The Pew

survey found that although most Western Europeans still identify as Christians,

for many of them, Christianity is a cultural or ethnic identity rather than a

religious one. Sahgal calls them “post-Christian Christians,” though that label

may be a bit misleading: The tendency to conceptualize Christianity as an

ethnic marker is at least as old as the Crusades, when non-Christian North

Africans and Middle Easterners were imagined as “others” relative to white,

Christian Europeans. The survey also found that 11 percent of Western Europeans

now call themselves “spiritual but not religious.”

“I

hypothesize that being ‘spiritual’ may be a transitional position between being

Christian and being non-religious,” said Linda Woodhead, a professor of

politics, philosophy, and religion at Lancaster University in the U.K.

“Spirituality provides an opportunity for people to maintain what they like

about Christianity without the bits they don’t like.”

Woodhead

pointed to another finding in the Pew study: Most Western Europeans still

believe in the idea of the soul. “So it’s not that we’re seeing straightforward

secularization, where religion gives way to atheism and a rejection of all

aspects of religion,” she said. “We’re seeing something more complex that we

haven’t fully got our heads around. In Europe, it’s about people disaffiliating

from the institution of the Church and the old authority figures … and moving

toward a much more independent-minded, varied set of beliefs.”

The U.S.

hasn’t secularized as profoundly as Europe has, and its history is crucial to

understanding why. Joseph Blankholm, a professor at UC Santa Barbara who

focuses on atheism and secularism, told me the Cold War was a particularly

important inflection point. “The 1950s were the most religious America has ever

been,” he said. “‘In God We Trust’ becomes the official national motto. ‘Under

God’ is entered into the pledge of allegiance. That identity is being

consciously formed by specific actors like Truman and Eisenhower, who are

promoting a Christian identity at home and abroad, over against a godless

communism. It’s the Christianization of America—as a Cold War tool.”

The Pew

survey shows that 27 percent of Americans call themselves “spiritual but not

religious.” Even though they’ve left organized religion behind, many still pray

regularly and believe in God. This raises an issue for researchers, because it

suggests their traditional measures of religiosity can no longer be trusted to

accurately identify religious people. “I think people are doing things that

don’t mirror Christianity sufficiently enough for our categories to continue to

be as explanatory as they once were,” said Blankholm. “These categories are at

their limit—they’re in some ways outmoded.”

Sahgal

said she was aware of this problem, and sought to make the survey questions

more granular so they would capture reality more accurately than the traditional

questions alone would have done. So, for instance, the survey didn’t stop at

asking respondents whether they believe in God. It drilled down further, asking

whether they believe in God as described in the Bible or whether they believe

in some other higher power.

As

religiosity takes on forms that scramble our old understanding of that term,

it’s forcing researchers to ask themselves anew what we talk about when we talk

about religion.

“Those

challenges are going to get worse—and they know it,” said Blankholm. “But I

love that they’re developing a new vocabulary, because that’s exactly what we

need.”