Palestine: Diary of an UNRWA kid

|

| Ramzy Baroud 09/23/2018 |

Maintaining one’s dignity while living a dismal existence in a refugee camp is not an easy feat. My parents fought hard to spare us the daily humiliations that come with living in Nuseirat – Gaza’s largest refugee camp. But when I turned six, and joined the UNRWA-run Nuseirat Elementary School for Boys, there was no escape.

Not only was I a refugee on official United Nations papers, but in practice as well, just like all my peers.

To be a Palestinian refugee means living perpetually in limbo – unable to reclaim what has been lost, the beloved homeland, and unable to fashion an alternative future and a life of freedom, justice and dignity.

How are we to reconstruct our identity that has been shattered by decades of exile when our powerful tormentors have linked our own existence and repatriation to their very demise? Per Israel’s logic, our mere demand for the implementation of theinternationally sanctioned right of return is equivalent to a call for “genocide”.

According to that same faulty logic, the fact that my people live and multiply is a “demographic threat” to Israel. When Israel and its friends around the world, argue that my people are “invented“, not only are they aiming to annihilate our collective identity, but they are also justifying in their own minds the continued killing and maiming of Palestinians, unhindered by any moral or ethical consideration.

I grew up in Gaza resisting this Israeli effort to erase us, Palestinians. “Ramzy Mohammed Baroud: A Palestinian Refugee,” was stamped on every piece of paper that I acquired since the day I opened my eyes.

With an ever-increasing number of refugees in an ever-shrinking space in Gaza, our communal language was dominated by a vocabulary that four generations of refugees are painfully familiar with: murderous soldiers, fences, warplanes, a constant feeling of hovering death, hunger, military curfews, resistance, martyrs and, UNRWA.

Always UNRWA. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian refugees had accompanied our journey of exile from the very start. Only months following the Nakba – the catastrophic destruction of the Palestinian homeland and the exile of an estimated 750,000 Palestinians in 1948 – UNRWA became synonymous with our exodus and our ongoing odyssey.

Much can be said about the circumstances behind the creation of UNRWA by the United Nations General Assembly in December 1949; about its operations, efficiency and the effectiveness of its work, which attempts to cover the needs of five million refugees.

But for me, my family and most Palestinians, UNRWA was not a relief or charity organisation per se. Being registered as a refugee with UNRWA provided us with a temporary identity that allowed us to navigate 70 years of exile, roaming without a home or even a roadmap for our return to what was, for a thousand years and more, our historical Palestinian homeland.

It was as if the stamp of “refugee” on every certificate we possessed – birth, death and everything else in between – was a compass, pointing back to the places we came from; to my destroyed village of Beit Daras and not to the Nuseirat refugee camp; not to Jabaliya, Shati’, Yarmouk or Ein El-Hilweh, but to the 600 towns and villages that were destroyed during the Zionist assault on Palestine.

The existence of these villages may have been erased, as a whole new country was established upon their ruins, but the Palestinian refugees remained – subsisted, resisted and plotted their return home. The UNRWA refugee status was the international recognition of our rights.

Frankly, none of this mattered to me at the age of six. I stood in line like all the other kids at school; chanted whatever morning routine slogans we were told to chant; took my place behind the worn-out desk that bore the marks of generations of refugee children scratching their names and references to past wars and tragedies; and did everything that I needed to do to be a good UNRWA kid.

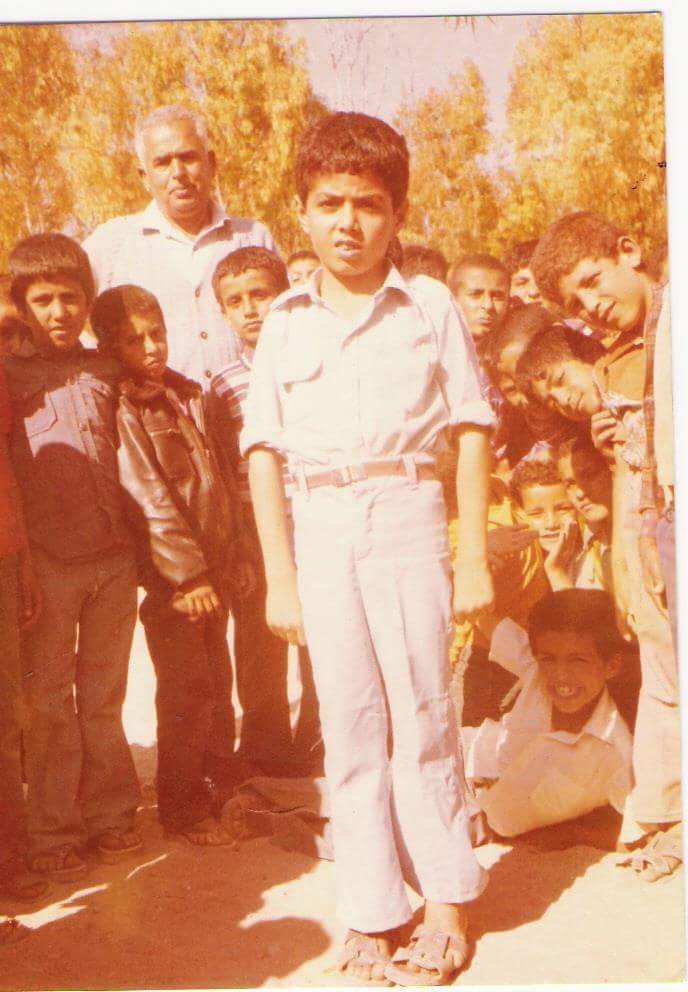

The author with his classmates and Arabic teacher, the late Abu Majed Abu Sharar, in Nuseirat refugee camp, Gaza in 1981. This is his UNRWA ‘fifth grade’ photo – made for each student in that grade by UNRWA staff [Courtesy of Ramzy Baroud]

And in first grade, when the first winter rainstorm came, I also learned how to reposition my desk to dodge the water dripping from the ceiling. Every roof of every UNRWA classroom I have ever been in was dripping when it rained.

In fact, one of my fondest memories from school was, when in third grade, our classroom flooded and our history, Arabic and math teacher, Mohamed Diab, asked us to sit on top of our desks as he continued the lesson. We shivered in our shabby UNRWA-supplied jackets, worn by many others before us. We huddled together with excitement as the water covered the floor of the classroom and as Mr Diab went on with his stories of past Arab grandeur from Palestine to al-Andalus.

It was at that UNRWA school that I painted my first Palestinian flag and experienced my very first Israeli army raid. As students, blinded by tear gas and smoke, ran in different directions, not knowing how to reach the main gate to escape, I remember the sixth graders going back in to rescue younger children. It was there and then that I saw what Palestinian courage means.

Mass flag drawing was a ritual that happened in the first week of each year. It was not a practice officially sanctioned by UNRWA, as the Israeli military administration of Gaza detained children, heavily fined parents and shut down schools for what they deemed to be an illicit act. Waving or even possessing a Palestinian flag was a criminal offence in Gaza. We did it anyway.

Sometimes, in the first few days of school, a massive blue truck would pull into our school welcomed by the shrill excitement of hundreds of children. Within hours each pupil would be handed several used books, two new notebooks, a set of pencils, an empty art book and four crayons.

Those fortunate enough to possess the green, red and black crayons would share them with the rest as we all rushed to draw as many Palestinian flags as possible.

Israeli soldiers always anticipated our collective rebellious act and waited for us like vultures in the streets. Many UNRWA kids were handcuffed and hauled to the army “tents” – a massive Israeli army encampment separating Nuseirat from the Buraij refugee camp – many crying for their parents and beseeching God for mercy.

I once threw my bag in a thorny bush to escape the wrath of the Israeli soldiers. Retrieving it felt like being poked by a hundred needles all at once.

The Israelis also terrorised us with their constant raids on UNRWA schools. Thousands of children and youth were killed and wounded that way, most notably during the First Palestinian Intifada of 1987. Our protests often started at UNRWA schools and it was in these same schools we also met to console one another over the wounding and martyrdom of fellow classmates.

No, the Israeli war didn’t target UNRWA as a UN body, but as an organisation that allowed us to maintain our identity as refugees with inalienable rights, demanding justice and repatriation to our homes. UNRWA fed in us the hope that one day we will shed what was meant to be a temporary identity in favour of our true identity, going back to being us again, a Palestinian people, an ancient nation that predates Israel by centuries.

It is largely because of these experiences that UNRWA is an essential part of my identity as a Palestinian refugee. This intrinsic relationship is not predicated on the services that UNRWA provides or fails to provide, but rather on the political and legal principles its existence is based on.

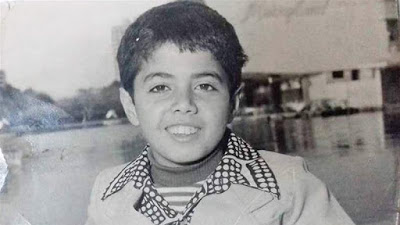

The author with his father at the Cairo Zoo in 1979 [Courtesy of Ramzy Baroud]

When I entered the UNRWA school, I also got my first food card. I rarely used it at the “tu’meh” (literary meaning “feeding”) – UNRWA’s feeding centre in our refugee camp. Even at a very young age, I loathed that experience. I hardly cared for that single slice of dried bread, half an egg and half an apple. Standing in that long line of impoverished children at the tu’meh – a place that reeked with the stench of a thousand boiled eggs – was hardly ever a pleasant experience.

A few weeks later, I secretly gave my UNRWA food card to another poor classmate, a Bedouin boy by the name of Hamdan, whose family didn’t qualify for refugee status. That was not a virtuous act on my part; UNRWA’s food was simply awful.

Yet, despite its leaky school roofs and stale bread, UNRWA was and remains essential and irreplaceable. As far as Israel is concerned, the refugees were meant to be “undefined” – in fact, that was exact term written in my Israel-issued laissez-passer in the space for nationality. The founders of Israel envisioned a future where Palestinian refugees would eventually fade away, disappearing into the larger population of the Middle East. Seventy years on, the Israelis are still entertaining that same illusion.

Now, with the help of the anti-Palestinian US administration of Donald Trump, they are orchestrating even more sinister campaigns to make Palestinian refugees vanish through the destruction of UNRWA and the redefining of the refugee status of millions of Palestinians. By denying UNRWA urgently needed funds, Washington wants to enforce a new reality, one in which neither human rights, nor international law or morality are of any consequence.

What would become of Palestinian refugees seems to be of no importance to Trump, his son-in-law and adviser, Jared Kushner and other US officials. The Americans are now insolently watching, hoping that their callous strategy will finally bring Palestinians to their knees so that they will ultimately submit to the Israeli government’s dictates.

The Israelis want the Palestinians to give up their right of return in order to get “peace”. The joint Israeli-American “vision” for the Palestinians basically means the imposition of apartheid. My people will never accept this.

The latest US-Israeli folly will prove futile. In the past, successive US administrations have done everything in their power to support Israel and to punish the supposedly intransigent Palestinians. The right of return, however, remained the driving force behind Palestinian resistance, as the Great March of Return demonstrated in Gaza earlier this year.

All the money in Washington’s coffers will not reverse what is now a deeply embedded belief in the hearts and minds of millions of refugees throughout Palestine, the Middle East and the world.

Many years after joining the UNRWA education system, I still identify with that UNRWA kid that I was. Sometimes, I wonder what has befallen my old desk in my first UNRWA classroom. Has it collapsed under the weight of the years of use and successive wars?

If it is still standing, I truly hope that my doodles are still there. I carved a map of historical Palestine, encircled it with a ring of flowers and wrote under it: Ramzy Baroud. Palestine. Freedom. Justice. Resistance. Raed Muanis. Raed was a friend of mine, a neighbour and another UNRWA kid, who was shot dead by Israeli soldiers who spotted him running with a small Palestinian flag.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.