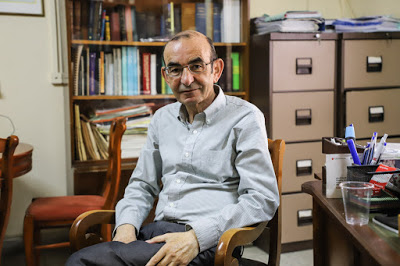

“I’ve been obsessed with time” – a visit to Raja Shehadeh

|

| Jaclynn Ashly – November 20, 2018 |

Palestinian author Raja Shehadeh has used his pen to delicately trace the contours of Palestinian history and landscapes, bringing readers into the harsh and complicated realities that shape daily life in the West Bank, where some two and a half million Palestinians have remained under an Israeli military occupation for more than half a century.

Shehadeh, who also practices law, wrote his first book in 1982, titled The Third Way: A Journal of Life in the West Bank, which painted a nuanced portrait of life in the occupied territory and created the ideological foundation for his future books.

“[The book] started when I went to the United States for the first time,” the 67-year-old told me at his office in Ramallah city, where shelves of legal books and documents line the white walls.

“I met a close friend of mine, who, although he is Palestinian and follows things here, he really had no idea what life was like here,” he explained. “When I returned [to the West Bank] I wrote him lengthy letters trying to explain how it is day to day. And it wasn’t a dramatic thing. It was little harassments and difficulties that people outside could not imagine happening at all.”

“I realized there was a need for such writing, and I expanded it into a book,” he said.

The book consists of stories and journal entries written by Shehadeh. Its title is derived from a saying among inmates at the Treblinka extermination camp in Nazi occupied Poland during the Holocaust: “Faced with two alternatives, always choose the third.”

In Palestine, he uses this saying to explore the options Palestinians have under Israel’s occupation: to either face “exile or submissive capitulation” or “blind, consuming hate.”

The third way is sumud, or steadfastness, a word used by Palestinians to articulate the act of staying on the land, regardless of the difficulties in doing so, in order to resist Israel’s ultimate goal of expelling Palestinians from their lands.

Shehadeh has since written 10 books, his most popular being Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape, which explores his changing relationship with the landscape of the West Bank owing to Israel’s settler colonial project.

He has a new book set to be released next year, titled Going Home. Although Shehadeh did not want to speak at length about the focus of the book, he said it explores aging and the changing perceptions of time as “you become closer to the end.”

“I’ve become rather obsessed with time,” Shehadeh said. “Maybe that’s why it bothered me so much that you showed up late.” He smiled and chuckled – the first sign of warmth he showed me since I had agitated him by arriving a half hour late. (I had used the wrong café as a reference point to his office.)

Shehadeh lives a simple life in Ramallah city, gardening, reading, listening to classical music and, of course, writing. Shehadeh has kept a sometimes daily — sometimes weekly – private journal for decades, allowing him to revisit old events, feelings and perspectives, transforming blank pages into literary works that have earned him international acclaim.

“I have a practice of always carrying around a small piece of paper or notebook and jotting things down,” Shehadeh told me. “It’s not a journal that I make myself write. I write when I need to in order to explain things to myself, or when I’m coming to terms with things.”

From law to literature

Shehadeh, one of the founders of the Palestinian human rights group al-Haq, had always wanted to be a writer. However, after the publication of his first book, “I realized there was a lot of work to be done in the legal aspects and the human aspects [in the occupied West Bank],” he said.

He instead dedicated most of his time to challenging Israel’s occupation and human rights violations through international legal frameworks.

“The biggest asset for Palestinians is the law,” Shehadeh told Mondoweiss. “Because the law is on our side. To some extent [at the time] there was more interest and shame among the international community regarding international law.”

Shehadeh served as the legal adviser for Palestinians during the Madrid peace negotiations in 1991, but left over disagreements with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)’s focus and priorities, which the writer said valued political expediency and the return of exiled leaders over issues facing Palestinians on the ground.

“The PLO agreed to terms that, from the beginning, I thought were too restrictive,” Shehadeh said. “It would have taken great effort to bring in issues that are so relevant to us [Palestinians] here, such as [Israeli] settlements and the land.”

He sipped from a cup of coffee an assistant had brought, and then went on: “It was only about creating a self-government for Palestinians. In my mind, [the negotiations] were leading to Israel unilaterally confirming and consolidating what was already happening. I decided it was futile and left.”

Years later, the Oslo agreements were signed in secret between the PLO and the Israeli government, dramatically altering life in the occupied Palestinian territory. The agreements broke up the land in the occupied West Bank into Areas A, B, and C, leaving more than 60 percent of the West Bank under full Israeli military control, while the newly established Palestinian Authority (PA) was permitted to govern just 18 percent of the land.

“I was very disappointed [after Oslo],” Shehadeh said calmly, his hands clasped together and resting on his knee. “It made a difference in my whole life, because until then I was giving up everything I could to the legal aspect of the struggle.”

“My life really changed. I felt that my work had amounted to very little in terms of political effectiveness […] Since Oslo, the Palestinian leadership has been excusing its failures and holding onto this deal, which they are bound to hold onto because they have no power to get out of it. And it has been downhill ever since.”

It was Shehadeh’s frustrations with Oslo that spurred him to leave al-Haq and direct his energy towards writing.

‘My father would feel very disappointed’

While Shehadeh always wrote on the side, even as he did legal work documenting Israel’s violations in the Palestinian territory, the first book he was able to dedicate a significant amount of time to was Strangers in the House: Coming of Age in Occupied Palestine, which he wrote when he was in his late 30s.

The memoir explores Shehadeh’s complicated relationship with his father Aziz, an accomplished lawyer who was stabbed and left to bleed to death near his home in Ramallah in 1985. Israeli authorities were accused of harboring political motives and not investigating the murder properly, and the case has since remained unsolved.

His father had, and continues to have, a profound influence on Shehadeh, and to this day the book was the most challenging for him to write, he tells Mondoweiss.

“Parents are extremely important and the perceptions and relationships change when one changes in time,” he said. “Whenever I tried to write something else, I would get back to that subject in my mind. So it was important and difficult to write.”

Since then, he has explored his relationship with his father in many of his books.

His father Aziz was one of the first Palestinians to promote a two-state solution and recognition of an Israeli state. In 1953, his father won a case against Barclays bank that allowed Palestinian refugees to access their accounts after Israel had seized them in 1948, when Israel was established upon the expulsion of some 750,000 Palestinians from their lands.

“I think my father would feel very disappointed [by the current state of the Palestinian territory],” Shehadeh said, without hesitation. “He realized early on, before many others, that we have to make a peace deal with Israel.”

However, Aziz was unique in his ability to see the potential positives in making a peace deal, Shehadeh noted. “He thought that Israelis and Palestinians working together would bring about a much better people, for both of us,” the writer explained. “We complement each other and we can do great things together.”

Shehadeh says that he has also inherited parts of his father’s vision. Like Shehadeh, Aziz understood the importance of Palestinians staying on the land. “My father would do everything possible to help Palestinians stay here. Every new person staying here was a gain.”

However, unlike his father, Shehadeh does not support a two-state or one-state solution to the decades-old conflict, noting that these discussions were “irrelevant.” Instead, the writer says his “dream” is “one region,” reminiscent of a Greater Syria, and believes this will inevitably become the future.

“It will come one day. But it’s a dream, just like the one-state solution is a dream,” he said. “It’s futile for us to dream now. I think we should focus on calling for the end of the occupation, and then we can find ways that we can live together. The question is how do we relate these two nations — Palestinians and Israelis together?”

The most pressing issue for Shehadeh is the right of return for Palestinian refugees — upheld by United Nations resolution 194 — who were expelled from their homes and lands during the Zionist takeover of historic Palestine in 1948.

“The right of return is a fundamental matter for Israel, because Israel bases its state mythology on the lack of a presence or existence of a Palestinian nation,” Shehadeh explained.

“So to recognize that there was a Palestinian nation living in what became Israel means Israel has to readjust its identity. And this is essential if there’s ever going to be peace”

‘To dehumanize them, you reduce your own humanity’

His latest book, Where the Line Is Drawn: A Tale of Crossings, Friendships, and Fifty Years of Occupation in Israel-Palestine, published last year, documents Shehadeh’s shifting perspectives and relationships with several Israeli friends throughout Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territory.

“I’ve been rather obsessed with the fact that when I go to a place, let’s say a checkpoint or a certain landscape that was changed, I see it both in the way it was and the way it is now,” Shehadeh explained to me.

“These two realities are in my mind all the time […] But it’s only because of my age and experience that I can see it in this way. But anybody who is an adult now, even in their 20s or 30s, will only know about how it is now. They will have no perception or imagining of how it was before.”

These thoughts created the framework for the book, exploring various “crossings” that have changed throughout the occupation. He said that he explores “how different relationships existed between Palestinians and Israelis at various levels, the relationship and continuity of the land, the way that it was open at one point, and how the crossings into Israel have changed.”

Shehadeh’s book, which in part focused on his relationship with his Israeli friend Henry and included personal letters exchanged between the two friends, examines these relationships in a humanistic, thoughtful and honest way.

In a land where even the most mundane aspects of Palestinian life are shaped by Israel’s occupation, it can be a personal struggle not to become bitter and resentful toward Israelis as a whole.

But Shehadeh has been able to transcend these feelings. “To dehumanize them [Israelis], you reduce your own humanity,” he said.

“I’ve passed through stages,” Shehadeh added. “The first intifada was one, when I would be so angry and so full of hate, and therefore feel myself reduced by the hate. I realized it doesn’t do any good. It doesn’t provide me a service and it doesn’t give my cause a service.”

“It doesn’t help me in my life or my understandings. So I got over it, and I never succumbed to it again.”

Continuing Sumud

Much has changed throughout the decades Shehadeh has been writing.

He remembers when it was difficult to get away with even mentioning Palestine in his books. When he did write that controversial nine-letter word, his books were often taken from public library shelves and torn apart.

“I remember going to Barnes and Noble, and noticing that one of my books — When the Birds Stopped Singing: Life in Ramallah Under Siege — was placed in the military history section,” he said, noting that he believes someone had placed it there so that no one would see it.

However, “now there are many books and intellectuals who are critical of Israel, which was not the case before.”

Meanwhile, he said, Israel has shifted farther to the right, with US President Donald Trump “allowing Israel to do whatever it wants.” Shehadeh believes that this is in fact bad for Israel.

“It is destroying the country,” he told Mondoweiss. “They are becoming fascists.”

For the daily life of Palestinians in the occupied West Bank, Shehadeh believes that it has become more complex. “I think in the past it used to be a lot simpler because we all understood occupation and we all thought it would end soon. But as time went on we realized that’s not the case,” he said.

“But it was clear where we were moving and the situation wasn’t confusing,”’ he continued. “At the same time, daily life was much more difficult and obstructed.”

However, now in the occupied West Bank, he says, there are more opportunities and possibilities for Palestinians. Particularly in cities like Ramallah, which boomed after 1997 becoming the de-facto capital of the West Bank, Palestinians have more access to economic ventures or other projects than they did before.

According to Shehadeh, this is all part of the continuing sumud, and represents developments that have made it easier for Palestinians to remain here. “If you think about Ramallah, as bad as the government [Palestinian Authority] is, they’ve managed to make it possible for people to lead their lives with clean streets and cafes.”

Ramallah’s active cultural scene, consisting of everything from visual arts, poetry and theater to hip hop and underground music, is an important element of sumud. “The assertion of the self is an important part of the resistance,” Shehadeh says.

“People are staying, and that’s very important. There is power in the fact that despite everything Israel has tried to do we are still staying,” he said, highlighting that the population of Palestinians and Israelis within Israel-Palestine is almost equal.

“That’s a great achievement considering how much Israel has tried to prevent it.”

Shehadeh politely glanced at his watch to check the time. We had been speaking for about two hours, and I thought it was best to finally end the interview.

The acclaimed writer walked me out. “Thank you for your time,” I said, and his reply was brief. “Yes, thank you. Good bye.” His eyes lowered to the ground as he gently closed the door in front of him.