Many will take credit, but this is the real reason Netanyahu delayed his annexation plan

|

| Anshel Pfeffer 02/07/2020 |

To avoid his biggest nightmare, the Israeli prime minister has to show some restraint

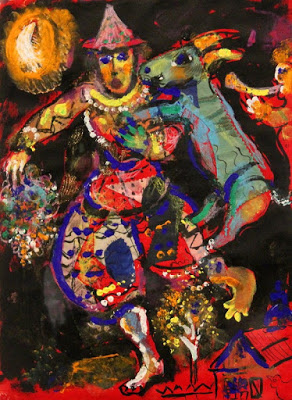

Benjamin Netanyahu may be a Litvak*, but 17 months ago, facing a deadlocked election, he followed the advice of the Hasidic rabbi in the old story: He brought in a goat.

You know the story. The Hasid goes to his rabbi to complain about his living conditions in a tiny stuffy cottage, with a complaining wife, noisy children, in-laws. The rabbi advises him to bring a goat into the house and next week the Hasid is back complaining that on top of it all, he now has a goat bleating, shitting everywhere and chewing up whatever it can get hold of. Remove the goat, the rabbi says, and you’ll finally appreciate your home as it is.

Since he first brought it up in a Channel 12 interview on the eve of the first of the three consecutive elections, annexation has been Netanyahu’s goat. It has been and continues to be an excellent diversion for the Israeli electorate from the prime minister’s corruption and increasingly autocratic ways, and now from his failure to adequately plan an exit strategy from coronavirus lockdown, leading to an escalating second wave of the pandemic and no clear path out of the economic crisis.

Annexation has served him on the international stage as well. For decades, the so-called international community has been pressuring Israel, to various degrees, to end the occupation, pull back from the territories, dismantle settlements and allow the establishment of a Palestinian state. Since annexation became an issue, the discourse has shifted to a much more comfortable place for Netanyahu: Just get rid of this goat. We can live with the occupation.

So now July has come, and with it the arbitrary date set in the Likud-Kahol Lavan coalition agreement from which Benjamin Netanyahu can bring the issue of annexation to the cabinet or Knesset. The fact that as of press time, nothing has yet happened on that front means little. It should have been clear from the outset that Netanyahu would have great trouble fulfilling his election promises from the three consecutive campaigns. Even the inclusion of annexation of 30 percent of the West Bank in Donald Trump’s deal of the century didn’t make it easier for him, as there would always have to be another side to the deal, one that Netanyahu could not force his right-wing base to swallow.

Netanyahu and his proxies will continue to claim that July 1 was never supposed to be the annexation date, just the beginning of the period in which the issue can be formally considered. Technically, they are not wrong. But the hype around the date has created a dynamic of its own. How much of this was planned?

Netanyahu certainly hasn’t planned the annexation. There is no map. No timetable. No drafts of legal documents to be brought to the cabinet or Knesset. All this reinforces the impression that annexation, at least for a significant part of the last 17 months, has been no more than a vague election promise to rally the right-wing base. But many who have spoken with Netanyahu in recent months have come away with the impression that at some point, at least since he managed to suborn Benny Gantz into serving in his government and secured his new term as prime minister, he fell in love with the idea. Annexation, or, as he calls it, applying Israeli sovereignty, expanding Israel’s borders so they include at least part of the biblical homeland, would be his historic legacy.

That period doesn’t seem to have lasted very long. Netanyahu’s enthusiasm for annexation is now waning. He won’t publicly ditch it of course. That would damage his credibility with the right and besides, the goat is still a useful diversion. But the chances of any significant annexation, or even a small “symbolic” one, ever happening now are diminishing by the day.

Many will try to take credit for successfully pressuring Netanyahu to desist. Benny Gantz, who finally rediscovered his balls this week when he said in interviews that July 1 isn’t “a sacred date” and that “a million unemployed” Israelis, laid off because of coronavirus, couldn’t care less about annexation, will be one. All manner of tiny left-wing organizations and think tanks will be patting themselves on the back. As will British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, whose last-minute plea was published on the front page of Yedioth Aharonoth’s July 1 edition. They all had very little influence on the matter, if any.

The one person who has most influenced Netanyahu in holding back on annexation is a 77-year-old man, currently sheltering from the pandemic in his home in Wilmington, Delaware. Joe Biden is the main reason Netanyahu is not annexing.

There are few politicians who have a keener understanding of polls than Netanyahu. He has several pollsters on his official and unofficial payroll, and keeps in touch with others. His polling brain-trust is heavily American and though they have misled at least once in the past, when he thought that Mitt Romney had a chance of denying Barack Obama a second term in 2012. He is fully aware now that Trump’s chances of winning in November are vanishing.

Until very recently, Netanyahu was convinced not only of his own invincibility, but that of his orange-faced friend as well. But as Joe Biden has opened up a convincing lead in recent weeks, that belief has evaporated. Netanyahu has seen how all his allies in the administration, with the exception of Ambassador to Israel David Friedman, are now distracted by trying to shore up a losing campaign. Not only is he not about to get the kind of unequivocal backing he wanted for annexation, but he has to contend with the growing realization that to go ahead would put him at loggerheads with the prospective new Biden administration from Day One.

Biden has let it be known, in his own voice and through proxies, that he is emphatically opposed to annexation. At the same time, however, he has resisted pressure from the left wing of the Democratic Party to go hard on Israel in other matters, and even hinted that should he be elected, he would not reverse Trump’s decision to move the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem.

Netanyahu’s biggest fear is that a new administration would restore the United States’ commitment to the nuclear deal with Iran, Obama’s cornerstone foreign policy. He is hoping to at least get a chance to argue his case with the new president for continued sanctions and a tougher American negotiation stance. Delaying annexation gives him an opening with President Biden. If the polling gap between Trump and Biden continues to widen, the prospect of annexation will grow more and more distant.

*Litvak: traditionally, a Lithuanian Jew, but more commonly a Jewish person who believes themselves to be intellectually superior and places great emphasis upon wordly items, such as money, cars, and prestige. They place little emphasis upon traditional Judaism and are instead obsessed with self-affluency and the need to belittle others for ascendency and fortune. (Urban Dictionary)