Lockdown may contain Covid-19, but it can’t curb the virus of Islamophobia in India

|

| Priya Ramani 15/04/2020 |

If 2018 and 2019 were the years India communalised rape, 2020 will go down as the year this country viewed a global pandemic through a Hindu-Muslim lens.

Activist Akram Akhtar was home in Shamli, Uttar Pradesh, when the clock struck 9 pm on 5 April, and the soundtrack of those responding to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call for a 9-minute lights-out echoed around him.

“There were loud shouts of Jai Shri Ram, firecrackers and the distinctive sounds of .315 calibre country-made pistols being fired. I heard the conch and prayer bells from the temple where loudspeakers played bhakti songs.” This continued for 45 minutes, he said.

In other parts of India too, Modi’s call to switch off lights and light a diya or shine a torch “to mark our fight against coronavirus” was interpreted by many Hindus as a show of majoritarian strength.

Worried that there might be communal tension, Akhtar got on his motorcycle and drove to some Muslim neighbourhoods. “It was dark and quiet. Unlike other days, not one person was on the road,” he added, attributing this to the fear fueled largely by the recent police violence against Muslim citizens protesting against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act in Uttar Pradesh (UP).

Corona fuels Muslim hatred

Since December, police in India’s most populous state has targeted Muslims, detaining thousands, raiding homes and even opening fire on people protesting against new laws that will put Indian citizenship through a religious sieve.

A bald headline in Time magazine holds up a clear mirror to our recent selves: “It Was Already Dangerous to Be Muslim in India. Then Came the Coronavirus.”

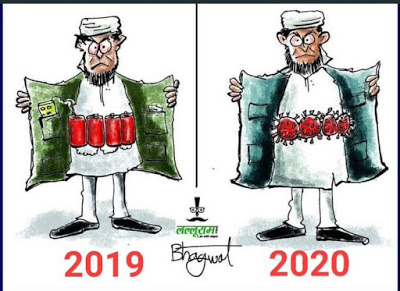

After attendees at a Tablighi Jamaat meet — held in Delhi before Modi’s call for a national lockdown — tested positive, fake news about Muslims intentionally spreading the coronavirus went viral. As India trended #CoronaJihad, our Islamophobia was on show for the world to see.

An indication of how fast the hateful rumours spread was that even the UP Police was forced to turn fact-checker.

In Sahranpur, 62 km from Shamli, the police issued a statement denying that Jamaatis quarantined in Rampur “created a ruckus” because they didn’t get non-vegetarian food and had excreted in the open. “After going through news reports, news channels and social media posts we have found that these reports are completely wrong and untrue. Saharanpur Police refutes this projected news in its entirety,” the official police handle tweeted.

After this, there were many more instances of the UP Police correcting and warning or arresting people and media organisations for spreading fake news or attacks against Muslims. An article in the Hindustan newspaper dated 6 April said the Meerut police found to be untrue the report that a maulana had spat on and bitten a shopkeeper. The shopkeeper was angry after an altercation over money and had used a coin to create bite marks.

Fake news and real damage