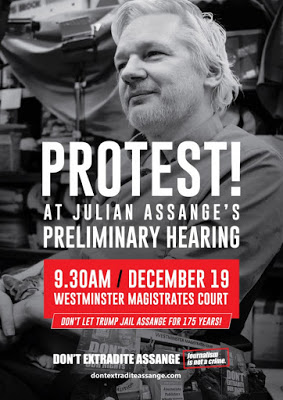

‘French activism’, intense struggles and ghost hearings at the Westminster Magistrates’ Court: report on Julian Assange hearings on 19 & 20 December 2019

|

| Monika Karbowska 02/01/2020 |

The whole world now knows that the person judging Julian Assange, Vanessa Baraitser, has been called a “wicked witch” by one of our comrades in the audience.

This is an epilogue that could have been jubilant for us, but the joy of the public tackle should not make us forget that the situation remains very serious: Julian Assange is going badly, worse and worse as the fateful hour of the “final extradition hearing” approaches and the lawyers’ “winning” strategy remains as mysterious for us as it was 6 months ago.

Moreover, the ultra-secret and secure phantom hearing on 20 December for the European Investigation Order, during which Julian was physically brought in and was therefore 20 metres away from us, was not organised to reassure us. Two crucial, hard and intense days that exhausted us. But two days of almost physical struggle to see him, to convey to him our support through shouts and slogans, to protest against the injustice of this unprecedented repression on a single man isolated and sickened by torture.

19 Decmber

I arrived a day in advance in London with the aim of understanding where and how the mysterious hearing of 20 December announced by some media will take place, but without any information being filtered through Julian Assange’s lawyers or Wikileaks sites. Along the way we learn that the final trial at the end of February will take place at the Woolwich court, next to Belmarsh prison, in a 25-seat courtroom with a large gallery open to journalists. How will we, human rights associations and committed activists be able to get in without the lack of space for everyone degenerating into tension and fighting? This is an obvious problem that the court grossly underestimates. For while the principle of “first come, first served” is fairer than the lists of authority drawn up by “Greeekemmy”, it does not solve the equation of lack of space. And we want more because we know that it is precisely popular pressure on the British authorities that can save Julian Assange from extradition.

However, for once the Westminster Magistrates’ Court has given itself the means to implement tough but fair rules of organisation. Our team arrived between 6.40 and 7.15 am. The Greekemmy group arrives at about 7.30am and the people will be more diverse than usual. At 9 o’clock we enter the building and we see on the list in the hall the name of Julian Assange at the head of the extradited people in room 3. In front of the room we will meet the head of the court bailiffs who regulates the flow with the security manager. She is very polite, makes us line up in front of the door and reassures us that the queue will be respected, even though we sometimes feel worried as soon as the word “list” is mentioned. But fortunately, she remains inflexible in the face of attempts to free ride. The journalists are much more numerous than usual, they sit on the seats in the corridor and talk. The team of lawyers is complete: Gareth Peirce, Mark Summers and Edward Fitzgerald the barrister we didn’t expect to find so soon at a simple case management hearing. Assistants carry heavy files with “Assange” written on the back. An elderly man whose face is familiar to me is standing right behind us. It is Tariq Ali whom Julian Assange met in 2012 during the Occupy London movements. Clair Dobbin is the head of the prosecution team, two young men and an older man. They lock themselves in a consultation room because the hearing does not start right away.

Journalists may enter at 9:30 a.m., in a group of ten. This time Joseph Farell has a press card and enters with them. The others protest. I am afraid that Mitie’s manager will sacrifice our seats to their indignation and I rush with my colleagues from Wikijustice as quickly as possible into the public box. Then the bailiff and the security manager bring in another 5 journalists who huddle together. The lawyers and the accusers take their places. The secretary is the same as on November 18 and December 13.

We sit in the front row in the middle. Tariq Ali is sitting next to John on my right. Behind us, as the group of “Greekemmy” clarifies who will take the remaining 9 seats, I notice a still young woman with brown hair and round face sitting in the back. She will turn out to be Stella Morris who had accompanied Julian Assange to the Ecuadorian apartment from 2015 until the end. I am intrigued by the presence beside her of a teenager between 15 and 18 years old who looks like her. What can a young person do in this kind of trial?. At 10:00 a.m. Clair Dobbin is in place for the prosecution in the front row. The three men accompanying him sit right in front of the screen where Julian Assange will appear. I manage after the hearing to corner the oldest one and ask him what his role is. He smiles and answers “observers”. On the prosecution’s side? Yes. They’re the “Americans” we’re looking for. Everything is almost in place, the security guards tell us to turn off the cell phones. A woman says she is handicapped and demands to be able to use a computer. Journalists are still protesting last-minute press cards. Apparently doctors have not been able to get in even though they have been assured that they will return with the list. The tense and suffocating atmosphere is weighing on us. The discontent is justified, but the security guards tell us that room 1 is impossible because it is not equipped. So we have to physically bring Julian in; this will not take place on Thursday but it will be possible on Friday for something other than his trial… Strange, the priorities of this court!

Vanessa Baraitser comes in at 10 o’clock, we get up. Very quickly appears in the video on the right a dark room with 3 blue seats and the sign “HMP Belmarsh Visitor court room 1” with the small window. The judge asks: “officer, Mr Assange please”. The guard answers but remains invisible. One to two minutes go by. A silhouette passes behind the window, a slightly doddering gait, and Julian Assange appears. He sits as if with difficulty on the first seat. You can see half of him. Baraitser tells him to sit in the middle seat, which he does. This time he is filmed frontally and up close, which gives an impression of volume, and that he is not as thin as on December 13. He is wearing grey trousers, a light shirt and a sky blue sweater that seems a bit large. He is wearing his glasses and looking up. His hair is short, his beard is short. Next to us when Tariq Ali saw Julian, he shouted in fear. Something like “It’s not Julian, it can’t be”! looking at us in amazement. Alas yes, and since October, for the fifth time, we are getting used to this brutal show.

Baraister asks him if he can hear, he answers “I think so”. The judge pronounces his name and date of birth herself and asks him to confirm. He says “Correct” and puts his hands folded on his lap. His gestures are slow, his words are slow. He makes an effort, discreetly pushing his head forward as if he needed to get closer to focus. This time he doesn’t have black rings around his eyes, but he looks exhausted and remains motionless and prostrate. As always, an impression of sadness and indignation overwhelms us. Will we finally be able one day to express this anger?

Vanessa Baraitser introduces the “case management hearing”, the preparation of the final extradition hearings at the end of February. She gives the floor to Fitzgerald. Then one of the women behind me exclaims that we can’t hear anything. She is roundly called to order by the security officer, who threatens to force her out. Master Fitzgerald announces that the full extradition hearing is scheduled for 5 days but it would take 3 or 4 weeks, which is not false. He underlines the “great difficulty to see Mr. Assange”. He remains very polite, he even talks about being grateful for the extra time. Tariq Ali looks at us with an astonished look. I think he has never seen British “justice” or Julian Assange’s lawyers in action. I make him understand with my gaze that all this is unworthy of us but no longer astonishes us…

However, Edward Fitzgerald finally raises the political problem: for the first time since the beginning of this whole affair, it is finally said that extradition is forbidden for political reasons, and the reason is political! Of course Julian Assange’s lawyer does not go so far as to ask for the immediate release of his client… He says that 21 witnesses must appear, then he mentions a summary of the Spanish trial for spying in the Ecuadorian apartment which is obviously used as a procedural vice to counter the extradition request. I find it difficult to grasp the logic of this. To say that Julian Assange’s trial is not fair because the Americans were aware of their target’s defence strategy does not seem to me sufficient to invalidate the fact that the United States is giving itself the right to prosecute a journalist for his publications. Worse, I have the impression that this persistent idea of “technicality” precisely removes the issue of substance: the scandal of this exorbitant requirement to silence and punish someone who is not an American national and has published outside their borders. In 2011 the same lawyers were convinced that they would bring down the European arrest warrant on a technicality. But they lost because the European form is politically drafted in such a way that its formal writing cannot be challenged. It is the substantive defect that must be examined; that is to say, the complete file in the issuing country…Julian Assange had lost his freedom and now his health in this game of failed formal defects.

At 10.10 am Julian Assange approaches the screen, tries to follow, puts his arms on his thighs, in a position of listening and attention, for 1 or 2 minutes. Fitzgerald proposes January 16 as the deadline for submitting the evidence. But Clair Dobbin objects. When she speaks Julian Assange has a backward movement, his shoulders sag a little more, his gaze is empty. He can no longer concentrate. The more discussions about dates go on, the more he struggles not to sleep, like when you’re exhausted and the pressure of sleep is too much. Fitzgerald describes the date of 10 January as the “guillotine” (I liked the term but the famous instrument should have been turned here against the ruling elites): he describes the enormous files to be studied, 40,000 pages of Chelsea Manning’s alone and the documents from the Spanish trial. Moreover, it would take at least a day and a half to prove that the court does not allow extradition for political reasons. In my opinion, it would take longer. Julian Assange stands there like he can’t hear. It is confusing and disturbing to see that the accused cannot participate in his trial and that we are getting used to having everyone speak for him. The lawyer then appears as a kind of guardian in the mode – he is sick so the lawyer takes his place. The “Americans” follow the events with attention. In the battle of the dates, the judge doesn’t even pay attention to Assange anymore, she talks to the lawyers and to Clair Dobbin, who is defending his butter bitterly. In the absence of a British prosecutor, the war was fought directly between Julian Assange’s lawyers and the Americans. The British state has even abandoned its role as arbitrator and abdicated its sovereignty… Julian Assange looks more than ever like a human being in a cage. I can see that he makes an effort to touch the papers in the file he is holding in his hand, but cannot. Fitzgerald then asks why the Belmarsh court was chosen for the trial, but the judge doesn’t answer. The lawyer then looks at the video screen, but Julian Assange says nothing and the lawyer is satisfied and does not insist. While he could have spoken louder and seeing his client’s non-response, he says “stop, we can’t go on like this”.

This is even more blatant during the 10:30 a.m. break. While the judge is gone, the courtroom goes about its business. Lawyers stand aside. We see a small square on the screen that shows what Julian Assange sees from the courtroom: he sees only the judge and the front row. Logic would dictate that his lawyers talk to him, greet him, nothing, they run out of his field of vision and he remains alone. On the other hand, the three “Americans” stand up. They are standing in front of us and look at him with a greedy and satisfied look on their faces. They look like they are watching their game. We are behind them and we see their merry-go-round, their smiles heard. We can’t hear what they’re saying to each other, but they’re obviously happy. We are bubbling in our helplessness and we can’t wait for this break to end. Because those who have the right to speak to Julian Assange do not do so and we are forbidden to speak to him, to write to him and to give him the slightest sign… We’re being made to participate in the isolation that we’re inflicting on him. Finally, ten minutes later, the ping-pong of dates starts again. Everyone is talking about “more flexibility” and pulls out his diary: “‘Can you do January 20th, January 21st? No, I can’t do that. Then maybe the 22nd? Let’s see if those dates are possible.” It’s confusing for us.

Vanessa Baraitser finally turns to Julian Assange: “You will appear on January 14th for the call over hearing and January 23rd for the next management video hearing.” No one bothered to ask for a physical trial anymore. Baraitser doesn’t even ask him anymore if he understood. It’s obviously so bent that she doesn’t care. He doesn’t react to the announcement of the dates. Then he says, “I’ve heard the program”. I distinctly hear the word “schedule”. His voice is hesitant and choppy. That’s when John gets up and approaches the window. Without shouting he says in a loud voice “I enjoyed the pantomime with the Judge in “wicked witch”, the wicked witch “… John utters three sentences. The emotion is at its peak. It’s stupor. The security guard enters our space and grabs John by the arm, but John resists. I take the manager’s arm gently to calm him down… In a confined space this hand-to-hand confrontation with the ultimate institutional violence is strange. Julian must have heard the beginning of John’s scream before the guard realized and turned off the screen. Baraister runs away, Fitzgerald and Dobbin who were talking to each other are stunned, motionless, gawked, face to face, the audience is evacuated, as one feels the fear that the emotion raised by John might degenerate.

I’m so hot that I get dizzy and lose my balance trying to pick up my things. Security is all around me, they’re afraid we’re going to invent yet another action. We find ourselves in the corridor a little stunned. I grab the American and ask him who he is. Then we see Joseph Farell, Tariq Ali, Stella Morris locked in consultation room number 2. The young boy is also sitting on the floor there. When he comes out I try to understand his role in this case. He tells me he’s a student doing research with Gareth Peirce. The hardest part, the hearing the next day, is still ahead of us.

But in the evening I can relax, telling myself that with a bit of luck Vanessa Baraitser will go home, meet her family tonight and think that she has been called a “wicked witch” by a lucidly desperate man just a few days before Christmas. Maybe she’ll be tired of taking on this role and will give Julian Assange the greatest gift: justice…

We understand that the media presenting tomorrow’s hearing as the “legal team” trial against the Spanish company Undercover Global accused of violating privacy and corruption does not tell us who exactly the plaintiff is. We do not know whether Julian Assange is the plaintiff or a witness. The next day will be another intense and active day, spent tearing out the information withheld by the court and trying at all costs to get a glimpse of Julian in the prisoners’ van and in the courtroom. Undoubtedly an important moment in his trial about which we know nothing for sure and from which the journalists will be absent.

20 December

Friday, 20 December 2019. Back to the Westminster Magistrates’ Court in pouring rain. This may be the real trial today, unlike yesterday’s pantomime so well characterized by John. Naturally, as Master Goscinski says, it would be enough for the judge to be courageous and order by the force of law of her independence the stay of proceedings and the immediate release of Julian Assange and we could prepare a nice and warm family Christmas for him for his first day of true freedom. Let’s dream, but not too soon. What happened to the independence of the judiciary in the West?

This December 20th the Court is not hostile to us but has prepared us dissimulations and trapdoors. At 7:15 a.m. several journalists are already waiting in front of the metal door of the side street through which the accused prisoners arrive. They are sure of their scoop, Julian will be there. I’m thinking of the Spanish court where this corruption trial is not supposed to be secret but quite public and accessible. It must be possible in this court to see Julian Assange talking from here on video to Spain. Our comrades join us and at 8 o’clock black cars leave the court in convoys, followed by vans from Serco and Geoamey companies. We go wild. Every time we think Julian might be in it. The photographers rush to the windows of the vans, flash, jostle me as I try to reach the same windows with our “SOS received” message. It’s raining, everything is wet, there’s a big puddle in front of the door and every time a car passes by we get sprayed with dirty water. The third van stops in the street before turning towards the entrance. We rush in. One of the reporters pushes me so hard One of the reporters pushes me so hard, I fall in the gutter. We drum on the car. I stick the message on the window above my head, one of the journalists tells me to get out, I say “No. Our message is important too”. Then I notice that the photographers look at their picture after shooting and see the prisoner’s head on their screen. None of them is certainly Julian, otherwise they would have quickly left with their booty. My paper is so wet that it sticks to the window of the van. I’m thinking if I shouldn’t let him get into the courtroom with the car. Because then maybe the message will stay and Julian will be able to see it, or someone will give him the message… Just one of the guards operates the door which goes up like a blind. She talks to us, tells us that she saw him, that she likes him… We go straight into the tunnel to talk to her, so we’re inside the courthouse. The private security people aren’t hostile to her, they just need to earn a living.

In the meantime our whole team has arrived and we decide to go inside. We have a small queue with the usual crowd of extradited persons, their families and their lawyers. It’s almost 9:30 a.m. and the listings on the billboards are still the same as the day before. We split up the work, we go to every floor, we check every door. Rumours are circulating that Julian arrived in a black car, that the hearing will be in courtroom 1… In front of this room I am talking to a Polish woman whose own extradition trial is taking place. She’s going to defend herself and she’s worried. It speaks a lot of Polish in the waiting room whose seats are full, about Christmas and the return home. I feel like I’m in a very familiar place. Finally an employee comes out of the office to change the lists. The one in room 3 has no less than 40 people to extradite! I’m the employee on the second and third floors dedicated to “crimes”. On the door of the last room 10 I read: “EIO Home Office”. European Investigation Order and Home Office, British Home Office: that’s it.

Reading the European directive of 2014 tells me that this new mechanism, which did not exist when Julian Assange was prosecuted in 2010, allows a suspect, a victim or a witness who lives in another European country to be questioned by an accelerated procedure via a simple video form or by a transfer order in the issuing country. The executing country, in this case Great Britain, must bring to the hearing representatives of its institution in charge of carrying out the procedure, in this case the Home Office. The delegates of the Home Office are also responsible, article 24, point 5 of the directive, for ensuring that the fundamental rights of the citizen being questioned are respected, please do not laugh.

But who is the complainant, who is the accused? We are waiting outside the door with another activist and two lawyers. That’s when the brunette woman who reports on Julian Assange’s hearings under the twitter name of Naomi Colvin appears with another young woman. At 10 o’clock we go in, room 10, only the judge and the clerk and the lawyers of cases number 1 and 3 are there. Soon a young man arrives as the defendant in case number 1. His case is adjourned because there’s no prosecutor. His lawyer is not happy but cannot say anything, he is dating his client. I’m trying to understand so I don’t lose anything of what the judge and the clerk are mumbling to each other, I’m too scared to miss the EIO. But it soon becomes clear that this can’t be where Julian is going to appear, the room is empty, there are no guards or security guards. Nevertheless, we persevere while understanding that nothing will be public and that we won’t be told the truth. Case 3 is postponed as well. With the judge gone, I ask the clerk “where is the IOE”? “Room 4”, he replies. On the way out I see Naomi Colvin and her friend confused. I yell “Room 4” and run to the first floor.

Is it a mistrial that the phantom hearing is announced publicly in Room 10 and then postponed orally on the sly in Room 4? It could be. Why the secrecy? So that we don’t know where Julian is who would normally go free? Room 4 is at the end of the corridor in the left wing, just above the armoured door where the vans bring the prisoners to the back office, next to the women’s toilets. It is empty and locked. We cannot communicate with the activists outside because of cell phone jamming. We wait, we talk. It is past 11 am when suddenly one sees in the consultation room 2 in front of room 4 Stella Morris, the young brown woman with the teenage boy of yesterday. I do not know exactly who Stella Morris is, the articles speak about still a lawyer of Julian Assange but I have doubts. Few people are telling the truth about their role in this case. So a man in a suit walks out of the room followed by the two protagonists. It’s Fidel Narvaez, the former consul, then first secretary of the Ecuadorian embassy under Raphael Correa. I’ve been in touch with him through left-wing networks. Nevertheless, I am surprised. Is he the plaintiff as the head of the administration of the Ecuadorian spied-on premises? What about Stella Morris the victim testifying as a former employee? Is the closed-door trial because of her son’s minority status at the time? But why hide it?

We’re politely asking Mr. Narvaez if and when Julian Assange will appear. At 2:30 he tells us. Security guards make the noise that it’s folded, that he’s gone, or that he’s only going to appear on video. Our friend John arrives then and tells us that this is it, Julian had arrived. The photographers are sure of that because they took the picture. It was a big van, the biggest van of them all. It’s noon, we can’t hope to pull Julian out of the bowels of the court back office. We can only hope they’ll give him something to eat and everyone’s off to lunch. We come back at 2pm and pass Stella Morris in the corridors who refuses to give us any information. The corridor is full of Poles and Romanians awaiting trial, we sit down with them, then little by little the corridor empties, the things are sent out. A little before 2.30 pm Fidel Narvaez arrives and waits in front of room 4. I introduce myself and tell him about yesterday’s hearing, that Julian is not well… He’s still very evasive. The case is very, very complicated. But today who exactly is the plaintiff? We don’t understand anything. Why the closed session, why not Courtroom 10, so Julian will be there or not? We just hope that Julian Assange is a witness and not yet accused of something. Ideally, a complaint on his behalf should be drawn up for violation of his privacy.

Mr. Narvaez is standing in one of the hallway seats waiting to consider a case. Around 3 p.m. I recognize Alistar Lyon, from Gareth Peirce’s office, who is walking 100 steps in front of room 4. He is the only lawyer Julian Assange spoke to during his appearance on 21 October. I’m not waiting, we must at least know what’s going on. He’s nice, we’re discussing the social situation and life in France. Yes, he is now Julian Assange’s lawyer. That’s all he can tell me. I tell myself that at least Julian won’t be alone. A few minutes later, around 3:10, room 4 is lit up and we’re getting busy inside. The manager opens the door and everything goes fast. Alistar Lyon rushes into the room, then a man and a woman, both civil servant types, come out of a consulting room and follow him. The Home Office, our friends say. Mitie’s security manager locks the door of the room while staying inside. But just before two security guards block the view by standing in front of the door, Julie had time to see Julian. She could see him standing, white hair cut off, rather shaved and without glasses. He is talking to Lyon face to face with behind the glass of the right-hand box. I can see Lyon well, but the security on the right is blocking the view. As soon as Julian sits down we won’t see anything. But we stay, hoping to see him and to put pressure on him.

Julian is behind two doors and a window, but only 20 meters away from us. It’s horrible and infuriating to know that he’s so close. When we think of the impenetrable walls of Belmarsh, the more secret prison where he’s so well hidden from the world. There are no words to describe our helplessness. It’s strange, because at the same time all our submission is voluntary. I know the profession of security guard, a proletarian job. No one would take risks. All we’d have to do is push them around, they’d fade away… But the others behind would make Julian disappear into the depths of the concrete dungeons and we’d be banned from entering or expelled…

So we camped outside the door in front of the men in the hope that our presence would be felt inside the room. So much effort on the part of the system to keep a man so weakened that the day before he couldn’t say his name or if he understood what was at stake in his fate from the sight of his loved ones… At that moment the relatives are us, there is no one else to be close to him. And outside are the activists whose clamour is rising. Louder and louder. The hall adjoins the wall facing the street of the rally. It is possible that Julian will hear “Free Free Julian Assange”, so sincere and powerful are the voices. The security guards move from one foot to the other, they are tired. I watch for signs of trouble so I can take action. They joke about the militant clamour, talking about “French activism”. There is no hostility on their part, but a kind of resigned duty to keep one’s job. We try to soften them up. We ask them to just allow us to see Julian through the airlock window, the security manager has locked the door from the inside anyway. What are the secrets of the hearing? No journalist can write anything real about it. Is it taking so long because you need an interpreter? How can Julian now concentrate during two hours of interrogation when the day before he couldn’t finish a sentence without hesitation? The hearing of a man in such a state cannot have any legal value. It must be stopped, released and treated in a place of trust so that he is able to defend himself. This is what Wikijustice has been asking for from the beginning…How is it that the Spanish judge does not see the deplorable state of health of the witness? Is there an English judge in the room or is the Home Office playing the role of the judicial authority? So many questions. And why is the manager of private security Mitie attending a trial that takes place in camera? In a closed session no one other than the litigants concerned and the judicial authority can be present. I see him next to the guard in the dark blue sweater moving furniture. In the end it is him who will open the metal door to let out the van where Julian Assange is locked up. The courtroom will be empty by 5pm, he will be left to work conscientious overtime. Fidel Narvaez left around 4.30pm without waiting for the end.

Because the hearing lasts two hours. It’s heavy for us too because we’re exhausted, but always on the lookout for the slightest possibility of seeing him. The activists continue to raise the voice of protest. Then suddenly the manager unlocks the door, the security guards fade away and I see Alistar Lyon storming out of the room and running towards the secretariat premises at the other end of the court. He has the defeated face of someone who’s faced some bad news. We’re worried about Julian. Then out comes an elderly man who could be the interpreter and the two Home Office officials. The agents tell us it’s over without formally kicking us out. We don’t want to miss Julian’s exit. We know they’ve already evacuated him out the back. We need to tell the activists to be on the lookout for the van as soon as possible.

It’s raining, it’s dark, but since we know it’s right behind the metal door we have to shout loudly because he can hear. We shout, some activists sing. The atmosphere is strong and supportive. There is a police truck and 6 or 7 cops in front of the door. They don’t look aggressive and they tell us that it’s to prevent us from entering the building. They know we’re not going to do it, everyone is far too obedient here. We wait another hour. They’re waiting for the Friday night traffic to pass so the van doesn’t get stuck in traffic? They want to take it through the other back door? We don’t know. We don’t know. Then slowly the door rises. First two vans enter empty, then one small and one large, both SERCO. We rush in, exhausted and angry. Especially on the second one, which everyone says Julian is in. Ten of us drumming on the armour, shouting “‘we are with you”, “‘free Julian. “…with all our might. Photographers are shooting inside. One activist, Cynthia, will tell us that Julian Assange was sitting on the side where she was standing and that she could see him when the photographer flashed and lit up the interior.

The vans leave the building and the police don’t stop us from following them down the street, so we run them down. There’s construction going on, the convoy is blocked 100 meters away. We run to catch up with the van again! We try to open the door… In older times people would have been more offensive, but who would dare to do today what the Resistance fighters of the 40s and the militants of the 60s and 70s did? We’re exhausted but we accompanied him to the end. Julian Assange is not alone. I hope he was able to take the cry of our indignation and solidarity inside the prison walls.