How activists got a Congress member to introduce a bill on behalf of Palestinian children

|

| Michael Arria on |

Earlier this year, Rep. Betty McCollum (D-MN) reintroduced her historic bill to the stop the detention of Palestinian children. H.R. 2407, the Promoting Human Rights for Palestinian Children Living Under Israeli Military Occupation Act, is a slightly different version of legislation that McCollum originally introduced in 2017. The bill would amend the Foreign Assistance Act to block U.S. aid from being used to detain children in any foreign country, including Israel.

McCollum’s bill currently has 22 cosponsors and no companion legislation in the Senate, but the issue of Palestinian rights continues to gain momentum throughout the country. Recent polling indicates that a majority of Democratic voters support conditioning aid to foreign countries over their human rights records. “I strongly believe there is a growing consensus among the American people that the Palestinian people deserve justice, equality, human rights, and the right to self-determination,” said McCollum in a statement after she introduced the bill, “It is time to stand with Palestinians, Americans, Israelis, and people around the world to reject the destructive, dehumanizing, and anti-peace policies of Prime Minister Netanyahu and President Trump.”

According to the Palestinian Prisoners’ Centre for Studies, Israeli forces arrested 69 children just this past August.

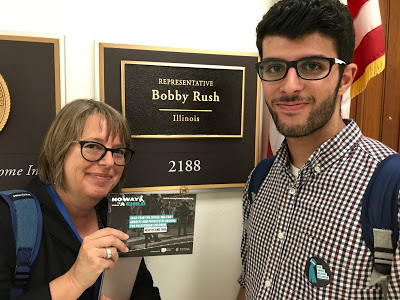

The fight for Palestinian self-determination largely remains a daunting, uphill battle in Washington, so how did a bill promoting the human rights of Palestinian children end up getting introduced in congress? If someone can answer this question, it’s Jennifer Bing. She’s worked at the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) for 30 years and has been involved in Palestine solidarity activism since the early 1980s. One of her current AFSC campaigns is No Way to Treat a Child, a project that was sparked by members of Defense for Children International-Palestine and AFSC. It’s this activism that led to the McCollum bill.

Bing spoke with Mondoweiss’ Michael Arria about how her feelings on pushing lawmakers has changed, how McCollum became an unlikely advocate for the cause, and what comes next.

Arria: You’ve been connected to this work for years. How did the activism around this issue end up leading to an actual bill?

Bing: That’s always a good question because for so long we never had an actual bill. There’s been letters that have been introduced over the decades but generally, resolutions and bills on Palestinian rights tend to be negative ones, not positive ones.

I’ve been working on this issue pretty much since 1982. And so I have a long view, shall we say, of Palestinian human rights activism, but also congressional work. And believe me, for many decades, I did not want to do anything on the Hill because it felt like a lost cause. People would even tell you in private that they supported your perspective or were interested in your story, but they weren’t willing to speak out publicly.

What had happened was for so many years, the ask for members of Congress was regarding U.S. military aid, to end aid to Israel. That always was the request. And that, as you see, is still a request. But it was just very hard, as I said, for anyone to speak out about it or to see progress on that front. So I think a lot of people said, let’s focus on doing the work to build up grassroots activism and let’s change the discourse and the rhetoric here around the country–then Congress will be the last ones to come around on the issues and I think that’s still true.

But, I think with the BDS call in the early 2000s, and the activism that developed from that, many saw that you can talk about human rights, you can do it in creative ways, and you can start talking about accountability. And that, I think, was very exciting and very energizing for the Palestinian solidarity movement. So, in 2014, when Defense for Children International Palestine decided to do some more serious advocacy in the U.S. around children’s rights, we thought, let’s test the waters and see if a narrower issue might might find some supporters. When we started the campaign, I don’t think we ever dreamed that we would have actual bills introduced, much less with more than a handful of co-sponsors.

But to step back for a minute….when you used to talk to people about these issues, the occupation was the rallying cry and, honestly, a lot of Americans didn’t know what that meant. Even members of Congress, when you would talk about the specifics of what occupation meant, like what it means to live under military law and to not have rights and to have so much for your life and livelihood controlled by an occupying force, they wouldn’t know. They’d say, “I didn’t know that there were separate roads,” or “I didn’t know that people were tried in military courts like that.” So, it was surprising to us, that for all the decades of doing education and speaking tours at churches, passing resolutions, etcetera, that a lot of people still didn’t understand what occupation meant. That was always the challenge. You would explain what it was like to live under occupation and people just wouldn’t believe it. I don’t think that’s true anymore. I think there’s been enough documentaries and enough people speaking about the realities there, that all those myths have been adequately challenged. But we were shocked that when we started to talk about child detention on the Hill, that many politicians basically said, “We never heard anything about this before.”

When we went to Betty McCollum’s office, we talked to her Chief of Staff. This was the spring of 2015 and we said, here’s the UNICEF report on this issue, these are the stages of detention that Palestinian children endure, and these are the numbers on kids that have been detained. We said, UNICEF itself describes this process as widespread and systematic. This is what occupation means. And I remember the Chief of Staff saying, “I have never heard this. I consider myself an educated person, but I never knew about this.”

So, we showed them some videos and and all our reports. Rep. McCollum had been on the Appropriations Committee for many, many years. She’s from Minnesota. She’s an army brat. Someone told us, “she wins hot dish competitions.” She’s not on the progressive caucus or anything like that. So she seemed like an unlikely champion, but she considered herself a person who believes in fairness and she had been a strong advocate for children’s rights and Native American rights. Once she started to read and see what was happening, she was appalled and said, “I’m not going to let this go by.”

However, those first few years, 2015 and 2016, all she was willing to do was a “Dear Colleague” letter, which I don’t mean to diminish. Dear Colleague letters are important; they’re a good barometer for activists and people who pay close attention to politics. They can raise an issue up and get more people talking about it. They’re probably not going to change a law, but they’re an indication that those members of Congress are hearing enough from their constituents. So, the first letter was pretty tame. It basically said, “We’re concerned about these children and we want the State Department to assess what’s happening.” And we thought maybe we would get two or three members of Congress to sign it, but we got 19. So we thought, “Oh my gosh, 19 members of Congress are willing to speak out on this issue. Maybe we’ve hit on something!” And I think everyone in the Palestine solidarity movement was kind of shocked. I mean, I was shocked that it happened.

So that put us on this trajectory of working with her office every year and pushing for stronger language. It’s still not a bill that cuts military aid, but it’s approaching that. The current bill is good until the end of this Congress. So, January 2021. I’m not sure what’s going to happen with it in 2020, there are so many factors going on with the presidential election, primaries, and other initiatives that will likely come out from “The Squad” and also from J Street. You have all these different players and there will be different things happening, but the great thing is HR2407 will stay as a marker. We’re going to continue to raise up this specific issue: our tax dollars should not be used to abuse children.

Rep. McCollum’s statement to Congress when she introduced this bill, which is the second one she’s authored, was quite strong and that mobilized other constituents to talk. I think some people watch the bill processes like a horse race — “Are we going to get to 25 cosponsors? Is the bill going to pass?” The truth is, it’s probably not even going to get out of committee given the current makeup of the Foreign Relations Committee, but that’s really not the point. The point is that more and more people are beginning to understand what we mean when we talk about about the occupation, or when we say we have to hold Israel accountable for human rights violations. We know what it is. We can tell that story. I think it’s been a great way to broaden the support for change and, again, I’m a good example of the kind of person that really didn’t do much congressional work and didn’t find it to be much of a priority, but now I think we really have an opportunity.

When I used to go to college campuses and talk with students about advocacy for Palestinian rights and I’d ask if people had contacted their member of Congress, there would be big eye rolls. There was absolutely no interest in that kind of work, and I understood that attitude, but this is actually one of the tools that we can use now. People are more interested in civics, or how to engage Congress. So now I see more young people wanting to attend lobby days or understand the CivicSummit. This goes for older retired people too. I just did a training session with an elderly group of Palestinian Americans who confessed that they lived here their whole life, but never really paid attention to Congress and they didn’t really understand what a bill was.

So, it’s an interesting moment where our activism isn’t just about advocacy, training, and civic engagement. It’s also about being effective when you talk to your member of Congress and why it’s important to pay attention to the positions that your member of Congress takes. None of this is new for our opposition. They’ve been building relationships in Congress and with the press for years, and that’s part of the reason they’re so successful. Meanwhile, our voices have always been marginalized or just not present. I’d go to Capitol Hill and talk to senators or staff and they’d say, “Well, we never hear from your side. Every week there’s somebody coming in from a PAC or one of the different organizations supporting the Israeli government and we never hear from your people.”

And, again, I don’t blame people. When they did call or visit, they weren’t necessarily respected for their positions. The change is slow. I don’t like to remind myself that there are 435 offices and only 23 of them are speaking out about the rights of Palestinian children, but the conversations are happening beyond just those 23. So, things have changed.

You mention that the bill only has 22 cosponsors, I think the last bill died with just 30. There was a piece in the The Intercept earlier this year about the difficulties McCollum is having getting a companion piece of legislation introduced in the Senate. However, at the same time there are candidates for president who are actually broaching the subject of conditioning military aid to Israel, principally Bernie Sanders. Then obviously it seems like the BDS movement has gotten more mainstream attention lately, as a result of “The Squad” and some of these resolutions. You also have a number of recent polls which show Democratic voters support the idea of conditioning aid to foreign countries in an effort to improve their human rights records. So, to an observer it might seem that the zeitgeist is changing here, but then they look at a concrete bill like this and there still seems to be so many challenges. Could you speak to this disconnect?

Well, it’s interesting. Candidates are talking about Israeli human rights violations on the campaign trail, but that tells me they’re being asked about it more. Maybe they’re more in touch with those polling numbers.

I’ve heard from at least a couple of friendly [Congressional] offices, “Well, if we’re going to stick our neck out on something, it’s got to be worth it.” Worth it? Meaning worth hearing? Worth getting the backlash from donors that are mad if they take a position? It’s so cowardly. I get very frustrated when I’m told, “You want us to put pressure on Israel to end the blockade of Gaza, but really, what can we do realistically?” It’s this absurd response. You can’t make a difference? You’re a Senator! I feel like the Senate is so much more entrenched than the House and still kind of old school in how they address issues. Everything is so transactional. Someone supports your bill, so you support theirs. I can’t stand it, honestly. But I’m thrilled every time I see that there is some mention of the issue, and I’m not giving up on the idea that legislation can be developed in the Senate. There are some progressive members that are going to come up as senior members after the next election, so it’s kind of a guessing game as to what will happen with it in the Senate.

I think faith communities are very significant when we talk about this bill gaining momentum. They have really continued to lift up the issue of children in detention. We have Christian leaders talking about it, Reconstructionist rabbis put out a statement supporting the bill, American Muslims for Palestine are mobilizing. The moral thought leader type of constituents are weighing in.