Alienation and counter-alienation

|

| Yasser Qous 06.02.2019 |

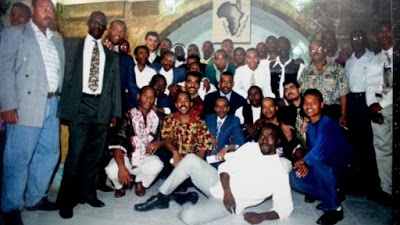

Yasser Qous, son of African-Palestinians, explains the feeling of foreignness experienced by Africans in 1970s Jerusalem and the alienation of African parishioners from each other at the time.

African Jerusalemites, or the “Takarneh”, as the Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref (1892-1973) described them in his comprehensive book on the history of Jerusalem (1961), are “one of Jerusalemʹs major families. They came there from Darfur and its environs. It is said that they are originally from Tikrit and that they belong to the Zawba branch of the Shammar tribe. The government used to employ them in the police force and they were entrusted with guarding the schools, which were held in the houses, homes and cloisters around the Haram al-Sharif. They are black, tall, and well-built.”

In a pamphlet entitled “Muslim Africans in Jerusalem”, which was published by the Islamic Endowments Department in Jerusalem (1984), the Palestinian researcher of African roots, Husni Shaheen, noted that they are “Muslims from a number of African countries, including Nigeria, Chad, French Sudan (which is now Mali) and Senegal. They are also descended from various African Arab tribes, including the Hausa, Salamat, Barqou, Zaghawa, Borno, Kanembu and Bulala.”

“Black” Africans

This article endeavours to illuminate and make sense of the status of black Africans in Jerusalem. It examines the impact of skin colour, what that means in terms of profession and place of abode, and how this is all related to alienation.

“Blood Prison” and “Ribat Prison”: in 1929 the two buildings were converted into residential quarters for Jerusalemʹs African population. Ever since they have commonly been known as the “slave prisons”, a name linked both to the buildingsʹ historical function and to the skin colour that people associate with slaves

Let us look first at the meaning of the word “black” in al-Maʹany dictionary. It refers, on the one hand, to skin colour and, on the other, to the place from which “black Africans” come.

The second definition clashes to some extent with that advanced by Aref al-Aref, which contends that they are from “Darfur and the surrounding area” i.e. from a specific geographical area with particular cultural and religious characteristics.

This leads us into a discussion about the impact and relationship of that geographical-cultural classification with the distinction which has developed in Palestinian eyes between the free black African and the kidnapped “slave”.

We will also look at the impact and scale of this vis a vis the “Takruri” (singular form of Takarneh) African, based on the distinction between cultural status and that of the African “other”.

Determining the social status of black Africans

Some may not even know that there are black Africans living in communities in various cities and refugee camps inside Palestine. Many researchers and historians e.g. Huda Lutfi, Aref al-Aref and Ali Qleibo, believe that the African connection with Palestine dates back to the Mamluk and Ottoman periods.

In Lutfiʹs study of the records and documents of the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem during the Mamluk period, she distinguishes between the status of the black “Takruri” African within the Islamic Ummah and the non-Muslim black African who was, to all intents and purposes, a “slave”.

Meanwhile, Aref al-Aref and Ali Qleibo both agree that the “Takruri” Africans were used as guards and to serve in the holy places in Jerusalem and Mecca during the Mamluk and Ottoman eras. And letʹs stop here at the notion of “service”, since it is misleading.

Qlaqshandi notes that it is a title which was bestowed by the Sultan. In “Lisan al-ʹArab”, and subject to the specific role and task involved, it refers to “anyone who serves someone else, be they male or female, a young male or female slave.” This begs the question: to what extent did this distinction among black Africans re-shape the cultural identity of the “Takruri” African?

The problematic relationship between skin colour, profession and place of abode

In an attempt to connect skin colour with the African heritage and the impact of this on the cultural identity of African Jerusalemites, I recall from memory the words that my uncle Hajj Jibril Ould Shine, rest his soul, used to recite to me, “Weʹre not slaves, weʹre free.”

My uncleʹs words were a barometer to measure the extent to which the concept of cultural separation had come into being, thus creating an identity that was estranged from its African forebear. It emphasised the genealogical links with the Arabian Peninsula. “Weʹre originally from Jeddah,” as the Mukhtar Mohammed Jiddah suggests in an interview with him in 1997.

If we look at the connection between profession, skin colour and physical traits, “being black, tall and well-built,” as al-Aref puts it in his book, was the reason why African Jerusalemites were chosen for security jobs. Herein is another indicator that allows us to gauge the relationship and role of these three key elements in determining the social status of black Africans. They adhere closely to the stereotype i.e. work that requires physical effort, not mental.

Yasser Qous writes that today the cultural boundaries between Palestinian society and the Takruri Africans as part of the Islamic community are blurred. Racist differentiation still exists, however, which is why the black African remains “the black slave” in the Arab imagination

The last link is the place of abode. In the case of Jerusalem, most Africans live in the African Quarter. It consists of two historical buildings, “Ribat al-Mansouri” and “Ribat al-Basiri” (ribat: a fortified complex, mostly used as a pilgrims’ hostel, but able to fulfil several functions), both of which were built during the Mamluk era in the 12th century near the Inspectorʹs Gate, which leads to the Haram al-Sharif.

From pilgrimsʹ hostels to prisons

At the end of the Ottoman era, specifically between 1898 and 1914, the two ribats were used as prisons by the Ottoman authorities. Ribat al-Basiri was reserved for Arab prisoners on death row and was known as the “jail of blood”.

Ribat al-Mansouri, the “ribat jail”, was reserved for Arab prisoners given custodial sentences. After 1929, both ribats were used as homes for the African Jerusalemites. Ever since they have commonly been known as the “slave prisons”, a name linked both to the buildingsʹ historical function and to the skin colour that people associate with slaves.

Some Jerusalemites try to soften the racist overtones of this labelling, with an over-idealistic view of Palestinian society: “weʹre all one, weʹre all brothers and weʹre all equals”.

Rather than implying any cultural or social racism towards black Africans, their use of this designation merely reflects their ignorance. Indeed, in their scenario, racism does not exist in Palestinian society as we are all “Godʹs slaves” in a religious sense.

The enduring image of black slaves

I wonder if we are really like that and whether itʹs true. After all, how can a utopian view explain or justify the continued use of a term such as “the slaves of Duyuk” when talking about the black-skinned population in northern Jericho near Ein al-Duyuk? Similarly, how can we still use the “slavesʹ quarter” as a label for those neighbourhoods inhabited mostly by black people in certain cities, towns and refugee camps inside the Green Line and in the West Bank?

In conclusion, the problems of differing definitions and a stereotype based on skin colour, profession and place of abode, are the cornerstones for understanding the status of black Africans in Palestinian society.

On the one hand, the term ʹblack Africanʹ has been subject to a process of appropriation and cultural exchange (as in the case of the African Takruri). On the other hand, it referred to a specific time in history (to the spread of Islam in Africa), as if al-Aref is saying that African people had no culture until the Islamisation and Arabisation of African society.

Notwithstanding this, I have tried in the above examples to show how the barriers between Jerusalemites and the African Takruri declined because they were all part of the Muslim community. At the same time, discrimination is still based on ethnic parameters: whether they are called Takruri or otherwise, the African remains the “black slave” in the Arab cultural psyche.

Yasser Qous

© Goethe-Institut/Perspectives 2019

Yasser Qous is a master’s student at the Department of History and Civilization of the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris. His research interests revolve around the social history of Palestine, with a focus on the historical development of the Afro-Palestinian community in Jerusalem.