Trump’s Criminalization of Muslims goes beyond Travel Ban

|

| Basima Sisemore – Jan. 30, 2018 |

On Jan. 19, a year after President Donald Trump’s first travel ban was issued, the Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments against the latest third version signed by Trump on Sept. 24, 2017. This version remains in full effect.

Under the ban, nationals from eight countries are subject to travel restrictions, varying in severity by country. Venezuela and North Korea are on the list, but the ban overwhelmingly targets Muslim-majority countries: Chad, Iran, Syria, Libya, Somalia and Yemen. Thus, what the American Civil Liberties Union has called a “Muslim ban” will have tremendous consequences on 150 million people, the majority of whom are Muslim.

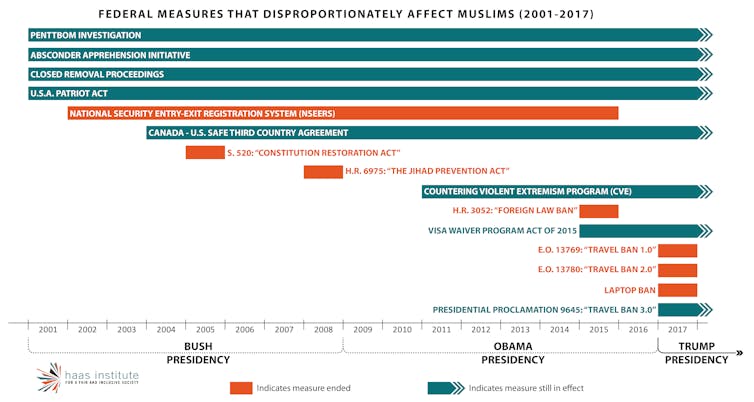

This policy did not emerge in a vacuum. In fact, findings from our recently published research expose 15 federal measures and 194 state bills that impact Muslims directly. Here’s a brief overview of some of the most critical yet overlooked measures.

Anti-Muslim federal measures

After Sept. 11, immigration became a key national security issue. As a result, 15 federal programs and initiatives were implemented that target and discriminate against Muslim individuals and communities. These measures rely on a narrative that depicts Muslims as untrustworthy and in conflict with American values. This framing has justified the surveillance, racial profiling and violation of citizens’ rights and protections enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

Federal measures.

Authors, CC BY

There are two important, often overlooked measures that have discriminated against Muslims and Arabs: the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System and 2015 changes to the Visa Waiver Program.

The Entry-Exit Registration System, created by the Justice Department in 2002, fingerprinted, photographed and attempted to track all non-citizen males over 16 years of age from 25 countries. With the exception of North Korea, all 25 countries had Muslim-majority populations and more than 85,000 individuals were registered in the system. The surveillance program was implemented as a counter-terrorism tool, but the program resulted in zero terrorism convictions. Although all target countries in the program were removed in 2011, its regulatory framework remained in place for 14 years and could have been reinstituted at any time.

In December 2016, President Barack Obama officially dismantled the program. Obama was motivated, in part, by preventing the incoming Trump administration from reviving the program. One of Trump’s campaign promises was to implement a Muslim registry.

Additional anti-Muslim travel policies were introduced following the November 2015 Paris attacks and the 2015 San Bernardino attack in California.

The attacks spurred changes to the Visa Waiver Program. The waiver allows citizens of specific countries to travel to the U.S. for up to 90 days without a visa. The 2015 changes exempted several Muslim-majority nations including Iran, Iraq, Sudan and Syria from these travel privileges.

Further updates were implemented in 2017 to target citizens of Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Syria, Libya, Somalia and Yemen and visitors to those countries.

Anti-Muslim state legislation

In addition to federal measures, our database has documented 194 anti-Sharia bills introduced in 39 state legislatures across the U.S. from 2010 to 2016. The anti-Sharia movement is responsible for the creation of these bills, sponsored by anti-Muslim organizations like ACT for America, and politicians who spread misunderstandings and fears around Sharia. This movement frames Sharia as a cruel and violent set of Islamic laws that are infiltrating U.S. courts to undermine American values and freedoms.

Sharia is a moral code founded on the teachings of the Quran and the Hadith – the teachings and actions of the Prophet Mohammed. Sharia is not the equivalent of Islamic law, but rather outlines how devout Muslims should engage with the world, from what they eat to how they conduct business and personal affairs.

Anti-Sharia bills, founded on the fear of “creeping Sharia,” identify Sharia as “foreign law” and thus ban its use in courts. However, U.S. courts do regularly interpret and apply foreign law, like Sharia, so long as it does not violate the U.S. Constitution.

In states that have banned the use of foreign law, judges are unable to enforce individual contracts that call for the application of Sharia. This restricts Muslims from upholding a range of personal agreementsincluding marriage, estate distribution after death, or awarding of damages in commercial disputes or negligence matters. For example, the Kansas State Legislature enacted anti-Sharia Senate Bill 79 in 2012. Later that year, a woman named Elham Soleimani, a Muslim immigrant from Iran, filed for divorce from her husband. Under the Islamic marriage contract she and her husband had signed, she was due US$677,000 in the event of divorce. The court refused to enforce the agreement, citing the enacted anti-Sharia law.

Anti-Sharia statutes not only fuel public fear around Islam and Muslims, but also prevent Muslims from using Sharia in rulings that call for cultural context.

Surveillance, travel restrictions, and anti-Sharia laws represent the ways in which U.S. policies discriminate against Muslims. As we anticipate the Supreme Court’s decision in June to either uphold or rescind Trump’s travel ban, the question remains: Will the Supreme Court continue to allow the legal discrimination against Muslims in the U.S.?

Basima Sisemore, Researcher, Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley and Rhonda Itaoui, PhD Candidate and Research Fellow, Western Sydney University