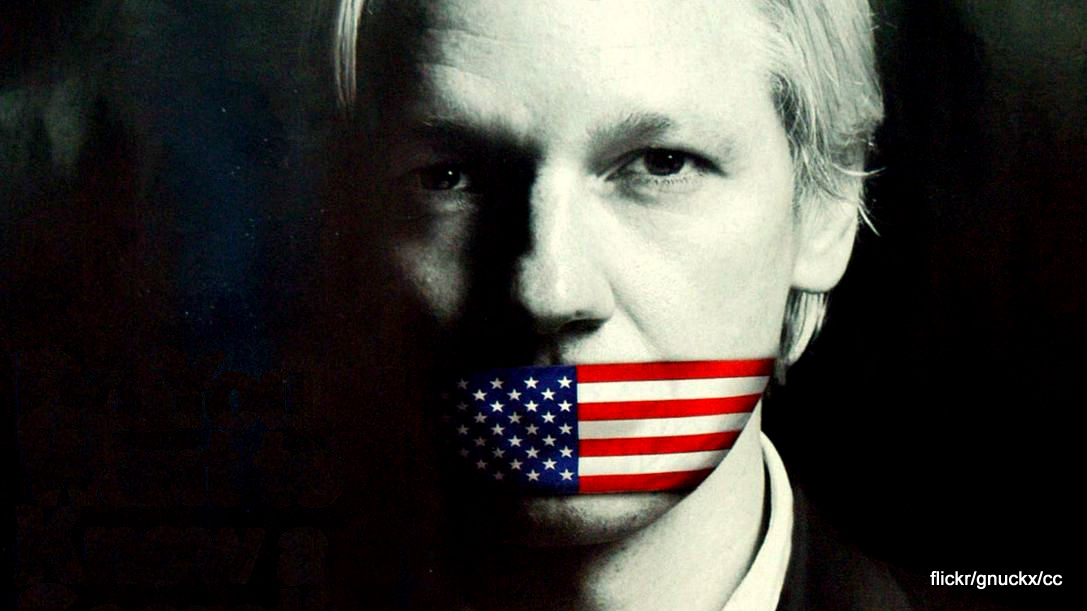

New Senate Bill Targets WikiLeaks, Russia, Independent Press and the First Amendment

August 28, 2017

WASHINGTON – The Senate Intelligence Committee is pushing Congress to label WikiLeaks a “non-state hostile intelligence service,” having adopted that very position in the Intelligence Authorization Act (IAA) it approved last month. The terminology used in the bill originates from a speech given in April by CIA director Mike Pompeo, who called the pro-transparency media organization a “non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted” by “hostile” nations.

WikiLeaks’ editor-in-chief, Julian Assange, has slammed the Senate bill as an attempt to legislate what he termed the “Pompeo doctrine.”

WikiLeaks has been under U.S. investigation since 2010 but the U.S. has failed to formally charge anyone in the organization for its role in leaking State and Defense Department documents.

However, WikiLeaks’ source in this case, Chelsea Manning, was convicted in 2013 and was only recently released from prison after receiving a pardon from President Barack Obama in January of this year. WikiLeaks came under scrutiny once again last year during the presidential election after publishing emails considered damaging to the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton.

The IAA’s 12,000-word text, however, makes only brief mention of WikiLeaks — in the last line of its 41 pages. The bill itself is mainly focused on Russia and strikes an aggressive tone regarding so-called Russian “interference” in the 2016 presidential election as well as Russian “influence operations.” If passed, for instance, the bill will call upon Dan Coats, the Director of National Intelligence, to develop strategies to counter these “threats,” and will essentially prevent cooperation between Russia and the U.S. on issues such as “cybersecurity” and “cyber threats.”

Mieke Eoyang, a former House intelligence committee senior staffer, told the Daily Beast that such measures will prevent “the White House from blocking the intelligence community from telling the committee and the American public what the true Russia threat is.”

Of course there are strong reasons to believe that the Russian “threat” has been overblown by the American political class. In particular, Russia’s alleged interference in the 2016 election – especially its supposed collusion with WikiLeaks in publishing DNC emails – has been independently confirmed by several investigators to have instead been the work of someone with direct access to the DNC’s servers, not a state actor like Russia. However, this information has proven to be politically inconvenient for many U.S. politicians and corporate media outlets.

The committee passed the bill by a vote of 14 to 1, the lone dissenter being Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR). Sen. Wyden specifically identified the inclusion of the WikiLeaks provision in the bill as his sole reason for voting against it. In a press release, he stated that “The language in the bill suggesting that the U.S. government has some unstated course of action against ‘non-state hostile intelligence services’ is equally troubling” as it “could have negative consequences, unforeseen or not, for our constitutional principles.” He added that “the introduction of vague, undefined new categories of enemies constitutes such an ill-considered reaction.”

In an interview with the Washington Times, Assange stated that “WikiLeaks, like many serious media organizations, has confidential sources in the U.S. government. Media organizations develop and protect sources. So do intelligence agencies. But to use this to suggest, as the ‘Pompeo doctrine’ does, that media organizations are ‘non-state intelligence services’ is absurd.”

Assange, continuing, stated that such an extrapolation “is equivalent to suggesting that the CIA is a media organization. Publishers publish what they obtain. Intelligence agencies do not. At their best, media organizations publish boldly and accurately and do not hide what they discover from the public. In contrast, intelligence agencies conceal information and spread propaganda.”

Most thought- and concern-provoking, however, were Assange’s statements regarding the potential implications of Congress declaring a media organization to be a “non-state hostile spy service.” Assange argued the importance of considering “where other media outlets lay on this spectrum. It is clear that if the ‘Pompeo doctrine’ applies to WikiLeaks, then it applies equally if not more so to other serious outlets.”

Indeed, central to the “Pompeo doctrine” is the assertion that WikiLeaks, given its alleged equivalence with a non-state intelligence service, deserves no First Amendment protections. During his speech in April, Pompeo stated that “we have to recognize that we can no longer allow Assange and his colleagues the latitude to use free speech values against us.” He later stated, during a subsequent Q&A, that “Julian Assange has no First Amendment privileges” because he is not a U.S. citizen.

As journalist Glenn Greenwald noted at the time, “the notion that WikiLeaks has no free press rights because Assange is a foreigner is both wrong and dangerous” — and could allow any foreign journalist or media organization to be prosecuted by the U.S. for publishing leaked information.

If Congress passes the Intelligence Authorization Act, it will essentially deprive WikiLeaks of the right to free expression and could allow the U.S. government to criminally charge employees of WikiLeaks, beyond Julian Assange, for their role in “espionage.” As Attorney General Jeff Sessions stated in April, however, Assange’s arrest is a “top priority” for the U.S. government, a fact that will likely remain unchanged regardless of the fate of the IAA.

Yet, the most clear and present danger to all journalists, if this bill is passed, could lie in reporting on information provided by WikiLeaks — or by any other organization the U.S. government decrees to be exempt from the First Amendment.

For instance, in 2010, then-Senator Joe Lieberman and former Bush Attorney General Mike Mukasey made the case that The New York Times should be prosecuted merely for publishing and reporting on leaked documents made available by WikiLeaks. Their legal argument was based on the grounds that no meaningful distinction could be made between the Times and WikiLeaks.

Seven years later, with the censorship of independent media like WikiLeaks already well under way, it may be only a matter of time before media outlets covering documents, state secrets — or any topic of which the U.S. government, particularly the CIA or Congress, does not approve — could find themselves on the chopping block for “espionage.”

The Intelligence Authorization Act – if passed – will not only do grave damage to the First Amendment and the freedom of the press, but will also criminalize the exchange of information.

The ultimate message of this bill is that the U.S. government is no longer willing to tolerate the publication of information that is at odds with its officially-supplied narrative — a narrative that, far too often, has been built on lies in order to justify the exploitation of resources, both domestic and global, and to expand the American empire.