Revealed: How dirty production of NHS drugs helps create superbugs

October 18, 2016

The emergency room at a hospital in Hyderabad, India, where antibiotic resistance is a public health crisis. Photo by Jagan. S

The NHS is buying drugs from pharmaceutical companies in India whose dirty production methods are fuelling the rise of superbugs, and there are no checks or regulations in place to stop this happening.

The growth in superbugs – infections which are resistant to antibiotics – is one of the biggest public health crises facing the world today, and pollution in drug companies’ supply chains is one of its causes. Yet the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has established that firms with a history of bad practice and pollution are supplying the NHS, and environmental standards do not feature in NHS procurement protocols.

New tests on water samples taken outside pharmaceutical factories in India which sell to the NHS found they contained bacteria which were resistant to the antibiotics made inside the plants.

This suggests industrial waste containing active antibiotic ingredients is being leaked into the surrounding environment. Studies have shown how this causes nearby bacteria to develop immunity to the drugs – creating “superbugs” – and that those resistant bacteria then spread around the world.

Responding to the Bureau’s findings, the Department of Health (DoH) said it would consider bringing in new rules for antibiotic factories which export drugs to Britain.

The Bureau’s investigation also established that at least three companies licensed to supply the NHS have not signed up to a new roadmap put in place following a recent United Nations antibiotic resistance summit, in which 13 global pharmaceutical firms pledged to review manufacturing and supply chains to make sure the release of antibiotics into the environment was being properly controlled.

Economist Lord Jim O’Neill, who conducted a major review into global antibiotic resistance, also known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR), told the Bureau the results of the tests were “deeply troubling”. His government-commissioned study found superbugs would kill more people than cancer by 2050 if no action is taken, and cited pollution in pharmaceutical supply chains as a major problem.

The Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Authority (MHRA) – which licenses companies to make drugs for the UK market and carries out audits of factories – told us it currently has no regulations around waste, and neither does the European Medicines Agency.

Both agencies require manufacturers to meet Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), a set of rules companies must meet to show their drugs are safe to be sold in the European Union (EU) or the UK. But GMP standards do not cover environmental emissions.

The influential purchasing power of national health services and authorities means they have the ability to bring about significant change in the way drugs are sourced and produced, said Natasha Hurley from the pressure group Changing Markets, which commissioned the water sample testing.

“Purchasers of antibiotics such as the NHS must immediately blacklist pharmaceutical companies with manufacturing practices that contribute to the spread of AMR, and to implement procurement policies that include environmental criteria,” she said.

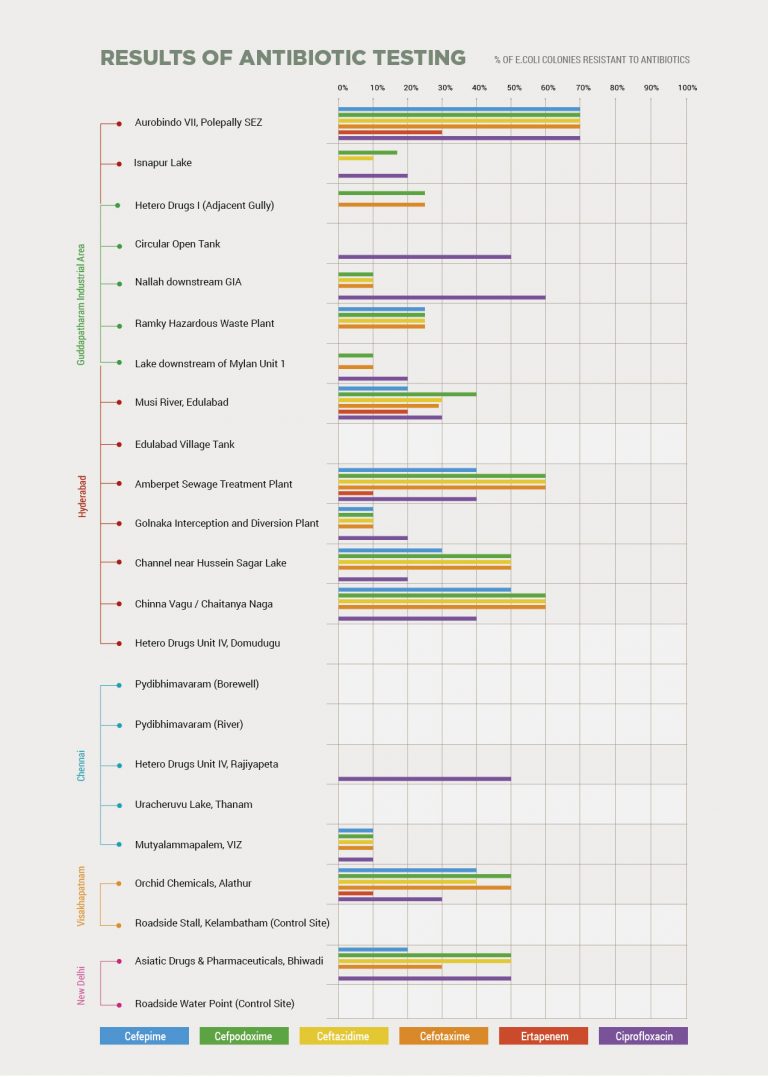

Changing Markets tested water samples collected at 36 locations across India – including sites adjacent to drug manufacturing plants as well as rivers and wastewater treatment plants – and found 16 contained antibiotic resistant E.coli bacteria.

The highest level of drug resistant bacteria was found in water samples originating from a factory in India run by multinational drug company Aurobindo Pharma.

Freedom of Information requests reveal Aurobindo, through its UK subsidiary Milpharm Ltd, has supplied antibiotics to NHS trusts across England during the past three years – including the UK’s biggest, Barts Health NHS Trust in East London. Aurobindo also has a £450,000-a-year contract supplying every NHS health region in Scotland with antibiotics including flucloxacillin, metronidazole and meropenem.

The company exports to more than 150 countries around the globe and 87% of its profits – which last year totalled about £200 million – are made from international operations, according to its most recent annual report.

Analysis of water originating inside the perimeter of the company’s plant near the Indian city of Hyderabad found that 70% of E.coli bacteria present were resistant to fluoroquinolones – a class of antibiotics classified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as being critically important to human medicine.

Fluoroquinolones are manufactured at the plant and despatched all over the world – though the Bureau does not know if drugs made at this particular factory are exported to Britain. However the factory was inspected and certified as meeting the EU’s GMP standards in 2013 – meaning it is authorised to supply the UK.

This graph shows the percentage of resistant bacteria found in or near these sites in India in tests supervised by Dr Mark Holmes at the University of Cambridge. The samples taken from outside Aurobindo’s pharmaceutical factory in Hyderabad are on the far left. They show the highest levels of resistance for all the classes of antibiotics tested in all of the sites visited. This included cefepime, cefpodoxime, ceftazidime and cefotaxime – which are all cephalosporin antibiotics, a class used to treat a wide range of infections. It also included ciprofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic and ertapenem, a carbapenem antibiotic. Fluoroquinolones are made at the plant and penicillin-type antibiotics are despatched from them. The tests cannot confirm the resistant E.coli are present as a result of antibiotic manufacturing. Mylan says it operates a zero discharge policy, so antibiotic-related material found in the lake near its Unit 1 cannot have come from there. The Bureau also contacted Hetero and Orchid Pharma, who are licensed to supply the US and UK markets, about the results, who did not respond or declined to comment.

Various studies have found “high levels of hazardous waste” and “large volumes of effluent waste” being dumped into the environment surrounding factories in India and China, where most of the world’s antibiotics are produced. Active ingredients used in antibiotics get into the local soil and water systems, leading to bacteria in the environment becoming resistant to the drugs.

Once established in the environment, the bacteria can exchange genetic material with nearby germs. They can then spread around the world through air and water, and by travellers visiting countries where the bacteria are prevalent.

Aurobindo was caught breaking pollution laws in 2012. The Andhra Pradesh Pollution Control Board ordered closure of two Aurobindo facilities (along with ten other pharmaceutical plants in Hyderabad) “in the interest of protecting public health and the environment”.

The company did not respond to the Bureau’s request for comment.

Changing Markets’ findings follow stark warnings in O’Neill’s review that a failure to tackle pollution from antibiotic production would exacerbate the spread of global superbugs.

The release of untreated waste products from substandard antibiotic factories “acts as a driver for the development of drug resistance, creating environmental ‘reservoirs’ of antibiotic-resistant bacteria,” said the report.

One major 2007 study found “shocking” levels of active antibiotic ingredients being discharged into a river in India, and concentration of the commonly-used antibiotic ciprofloxacin in the water exceeded levels toxic to some bacteria by 1000-fold.

Responding to the new findings, O’Neill told the Bureau: “Reports of this type of untreated antibiotic waste being released into the environment are deeply troubling, and it is the responsibility of all manufacturers – and their suppliers – to ensure that negligent or irresponsible practices do not add fuel to the fire of rising drug resistance”.

O’Neill backed a recent initiative by 13 global pharmaceutical companies to produce an industry “roadmap” to combat antibiotic resistance, pledging to reduce environmental impact of antibiotic production.

The pledge, signed ahead of a high-level UN meeting on AMR last month, included promises to review manufacturing and supply chains to make sure they adhered to good practices and were not releasing antibiotics into the environment. Aurobindo and Milpharm were not among the list of signatories to the document.

Aurobindo also sells antibiotics from the Hyderabad plant in the USA and supplies drugs for the American pharmaceutical company McKesson.

The DoH told the Bureau that emissions from antibiotic factories were a growing concern and one where strong international action was needed.

A spokesperson said: “Although manufacturing practices of companies that supply the NHS are closely monitored by the MHRA, there are no current rules around antibiotic supply. This is something we will consider carefully as our world-leading work on antimicrobial resistance continues.”

O’Neill’s review stressed that it was local populations whose health was most harmed by pharmaceutical pollution. India has become the epicentre of the global antibiotic resistance crisis, due to rampant overuse and misuse of the drugs in human medicine and livestock farming, as well as bad practice by factories.

A study published in the Lancet medical journal last year estimated the deaths of 58,000 newborn Indian babies a year were attributable to blood poisoning from infections resistance to antibiotics.

Dr J.V. Reddy, the chief doctor at Gandhi Hospital in Hyderabad, a state-run hospital with 1,200 beds, told the Bureau that half of all samples sent for testing, including blood and urine samples taken from patients seeking treatment, contained drug-resistant bacteria.

This included Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria and E.coli, Klebsiella and Pseudomonas bacteria – most of which contained enzymes which can break down penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics.

Some E.coli and Klebsiella found were also resistant to carbapenems, last resort antibiotics given when bacteria have become resistant to other types. “Every three days a patient at the hospital dies of sepsis, with antibiotic resistance contributing to these deaths,” Dr Reddy said.

Overuse of antibiotics, the drugs being given for the wrong illnesses, and multiple types being given in one go exacerbates the problem, as well as patients using them irregularly.

By the time they arrive at Gandhi hospital, most people have already been prescribed several antibiotics, he said.

Resistance spreads from India back into the rest of the world. An enzyme called NDM-1, which makes bacteria resistant to carbapenems, was first detected in 2008 in a patient who had been treated in a New Delhi hospital. It has now spread to countries across the world, including the UK.

‘I was blinded in one eye by an infection resistant to antibiotics’

Anji Reddy, a former farmer, was one of 13 people to lose vision in one of their eyes after an outbreak of a resistant infection. The 70-year-old, from a village near Hyderabad, went to the city’s Sarojini Devi Eye Hospital on June 30 for a cataract operation on his right eye.

A few days after the surgery, doctors removed his bandages and found his eye red, swollen and seeping with pus. Tests revealed it was infected with Klebsiella and E.coli bacteria that was resistant to antibiotics.

It is believed the solution used to irrigate his eyes during the surgery was contaminated. Three months later, Mr Reddy is still in constant pain and can no longer work to provide for his family.

‘I cannot do anything,’ he told the Bureau. ‘Earlier I used to tend to farm animals, clean the litter. I used do some digging. But now I cannot even see the path to walk”.

Thousands like Mr Reddy fall ill with drug resistant infections every year in India.