Yemen is facing calamity and it is time the world woke up

August 31, 2016

Homes flattened by air strikes. Boys killed by discarded cluster bombs. Babies dying in incubators. This is Yemen in 2016. MEE sent Peter Oborne to survey the devastation

Editor’s Note: Award-winning journalist Peter Oborne and Middle East Eye’s Nawal Al-Maghafi are among the few correspondents to have ventured into war-torn Yemen during the past month. In the first of a series of exclusive reports, they survey the devastation and reveal the culpability of the West for the carnage that is unfolding on a daily basis. Much of their reporting is from Houthi-held territory, where they were accompanied, and their interviews monitored, by Houthi minders. We are, however, confident that what they were told by their interviewees is authentic.

SANAA – The humanitarian calamity in Yemen entered a terrifying new phase of horror this month as air strikes on the capital city of Sanaa started again after a five-month lull.

Planes from the Saudi-led coalition bombarded the city following the collapse of peace talks in Kuwait. The assaults are destroying civilian infrastructure, and threaten to prevent food and desperately needed aid from reaching the capital.

A young girl undergoes hospital treatment in Sadaa (Mohammed Al-Mikhlafi/MEE)

Many of the attacks seem to have been indiscriminate. At least 16 people, all of them said to have been women and children, died when a potato crisp factory was struck.

The nearest military post was more than one kilometre away and a friend of the owner told us that there was no military activity on the site.

Saudi-led coalition air strikes also killed 10 people and destroyed a school in Haydan in the northern Saada province on 13 August, while an attack on a Doctors Without Borders (MSF) medical centre in Hajja left 19 dead and 24 wounded, prompting the charity to announce it was evacuating its staff from six hospitals in northern Yemen.

The coalition said it had set up an independent team to investigate incidents in which civilians are killed.

The strikes also targeted the Red Sea port of Hodeida and elsewhere across Yemen. Much of the country is already threatened with starvation.

The renewal of the air assault, and fresh evidence of the killing of civilians, will open Britain and the United States to fresh charges that they have been complicit in alleged Saudi war crimes and atrocities.

The two countries have supported the Saudi-led coalition since the start of the war 18 months ago – but the British Foreign Office has repeatedly denied that Saudi Arabia has been guilty of breaches of humanitarian law.

Ministers asserted that Britain had carried out an “assessment” which cleared Saudi Arabia of violations of international humanitarian law.

Late last month, in a dark moment of official embarrassment, the British government was forced to admit that it had repeatedly misled parliament over the war in Yemen.

In fact, the Foreign Office has now accepted that Britain had never carried out any such assessment – even though for months, human rights organisations have been presenting it with substantial evidence that atrocities have been committed.

‘If we had the medicines they would still be alive’

Middle East Eye travelled to Yemen as part of our own assessment of breaches of humanitarian law by the Saudi-led coalition.

We discovered indisputable evidence that the coalition, backed by the UK as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, is targeting Yemeni civilians in blatant breach of the rules of war.

Peter Oborne meets residents amid the destruction in Sanaa (Mohammed Al-Mikhlafi/MEE)

We saw evidence of the pitiless destruction of Yemeni homes by Saudi air strikes. We spoke to many of the survivors of these air assaults from the Saudi-led coalition, hearing harrowing stories of how they fled from their homes.

We also saw first-hand how the Saudis are carrying out sinister “double tap” air strikes.

This euphemism describes the practice of launching a preliminary strike, then launching a fresh attack when the emergency services come to pull the wounded from the rubble. This cruel strategy makes civilians victims twice over and kills them at the precise moment when they hope for rescue.

We were also told by doctors that the blockade of Yemen, legitimised by the United Nations Security Council, and backed by Britain and the United States to prevent arms supplies reaching the warring sides, has also prevented vital drugs and medical equipment from reaching the country.

At the Republic teaching hospital in Sanaa, the Yemeni capital, Dr Ahmed Yahya al-Haifi spelt out what he saw as the consequences of the Saudi blockade: “We are unable to get medical supplies. Anaesthetics. Medicines for kidneys. There are babies dying in incubators because we can’t get supplies to treat them.”

Al-Haifi estimated that 25 people were dying every day at the Republic hospital for want of medical supplies. “They call it natural death,” he said. “But it’s not. If we had the medicines they wouldn’t be dead.

“I consider them killed as if they were killed by an air strike, because if we had the medicines they would still be alive.”

Doctors told us similar stories elsewhere. There is also powerful evidence that the Saudi-led coalition has deliberately targeted hospitals across the country. Four MSF hospitals had been hit by Saudi air strikes prior to the organisation’s withdrawal from the country, even though MSF were careful to give the Saudi authorities their GPS positions.

In Yemen there are no leaders, no peace – and 10,000 dead

There are no innocent parties in this Yemeni war, whose immediate origins can be traced back to the Arab Spring in 2011 and the subsequent removal of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was notorious for his authoritarian and corrupt rule.

Saleh, an admirer of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, had governed Yemen since its unification in 1990 and North Yemen before that since 1978, cunningly positioning himself towards the end as a Western ally in US President George W Bush’s “war on terror” in a desperate attempt to survive.

This was not enough to prevent him from being forced out in favour of his vice-president, Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi in 2012. A national dialogue conference lasting two years failed to resolve differences between different parties and factions and came to an unsatisfactory end in early 2014.

Hadi, who is still the internationally recognised president of Yemen, soon faced an insurgency from the Houthis, a northern clan whom Saleh had tried to suppress during the course of six brutal wars.

Sanaa’s Bab al-Yaman gate, with Houthi banners hung from the towers (Mohammed Al-Mikhlafi/MEE)

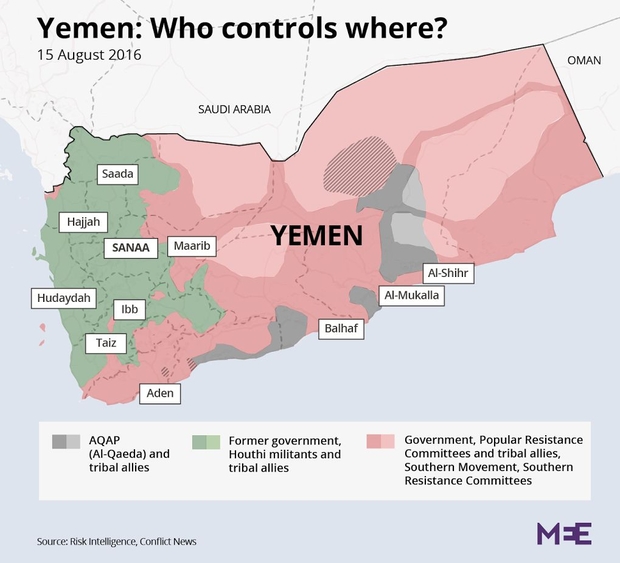

In 2014, the Houthis stormed down from their northern stronghold of Saada (the centre of their Zaidi religion, a variant of Shia Islam almost unique to Yemen) and seized Sanaa. Historically this north-western region of Yemen, and many other parts of Yemen besides, had been ruled by Zaidi imams until Yemen’s republican revolution in 1962.

Their slogan – God is Great, Death to America, Death to Israel, A curse upon the Jews, Victory to Islam – is painted or plastered ubiquitously on public buildings. Houthi soldiers, with Kalashnikovs flung over their shoulders, are a common sight on the streets.

According to some reports, both Saudi Arabia under the late King Abdullah and the UAE liaised with the Houthis, under the assumption that a Houthi advance southwards would be met by militias provided by Islah, the Yemeni political party which is close to the Muslim Brotherhood.

This failed to materialise and the Houthis marched into Sanaa unopposed in September 2014. Hadi at first welcomed the Houthis, perhaps seeing them as a way of undermining Islah.

If so, this was a terrible miscalculation: they reportedly placed him under house arrest and, in an improbable transfer of allegiance, entered into a binding alliance with their bitterest foe, deposed Ali Abdullah Saleh.

However, Hadi managed to escape (according to rumour, disguised as a woman in a burka) and fled to the southern Yemeni port of Aden. The Houthis pursued him there, and Hadi fled onwards to Saudi Arabia, from whom he begged assistance.

King Salman, who had ascended to the Saudi throne following the death of King Abdullah a few weeks earlier, responded to Hadi’s entreaties, convinced that the Houthi forces were proxies for Iran.

He assembled a coalition of Arab states which ever since March 2015 has launched punishing bombing raids. All attempts at peace talks have so far failed.

On Tuesday, Jamie McGoldrick, the UN’s humanitarian coordinator, told a press conference that at least 10,000 people were estimated to have died and three million Yemenis had been forced to flee from their homes. According to the World Food Organisation, much of the country is on the verge of starvation.

Traffic jams are sitting ducks for air strikes

At the start of the conflict the Saudis declared the northern city of Saada a military zone. This allowed them to bomb it indiscriminately. In Saudi eyes, residential homes became legitimate targets. They did drop notes warning people to flee, but the absence of fuel meant it was often impossible for them to do so.

As a result, Saada has been very dangerous to visit since the war began and until recently was a ghost city. We took advantage of a temporary and fragile ceasefire to visit the city.

For all of our journey we were accompanied by Houthi minders. Many of our interviews were monitored, sometimes intrusively: there is no other way of travelling through Houthi-held territory. We are, however, confident that our testimony is authentic, and that the people we met deserve to have their stories told.

There was a time when the 200km journey from Sanaa to Saada was no more than a four-hour drive along Yemen’s excellent metalled roads and well-constructed bridges.

Khaywan Bridge, two hours north of Sanaa. The destruction of crossings has caused long traffic jams (Mohammed Al-Mikhlafi/MEE)

This is no longer the case. There are numerous checkpoints and we had made 50 copies of our official permission to travel, issued by the Houthis, to present when we were stopped.

The early checkpoints after leaving Sanaa were manned by Yemeni army soldiers loyal to Saleh, working alongside Houthi militiamen. As we drove further north we saw less of the army as they were steadily replaced by Houthi fighters, members of so-called “revolutionary committees”.

The worst hindrance however, came from the Saudi bombing of the bridges, leading to huge traffic jams and delays.

Khaywan Bridge, a two-hour drive north of Sanaa, had been destroyed, causing a tailback of lorries stretching for almost a mile as they prepared to cross the river by an improvised ford alongside the smashed bridge.

Crossing the river did not cause too much of a problem for our four-wheel drive. We simply drove along the river bank looking for a crossing point.

But for trucks, many of which were bringing vitally needed humanitarian supplies, this was not an option.

One driver told us that he expected it to take him six or seven days to make what had previously been a simple journey down from Saudi Arabia.

These long tailbacks at river crossing points are sitting ducks for Saudi air strikes.

‘The skies are on fire’

As we headed north towards Saada, we saw more evidence of war: destroyed buildings by the side of the road and pathetic tents belonging to people fleeing the fighting at the Saudi border. These people were victims of Houthi as well as Saudi aggression.

Conditions in these camps are dire. There is little water or food and we were told that they were not served by humanitarian agencies. One widow, Halima Salah Abdullah, was huddled with her seven children in a tiny hut with walls stretching no more than four metres long and three metres across.

Camped by a roadside, the Awbali family have been driven from village to village as they try to escape the fighting (Mohammed Al-Mikhlafi/MEE)

She told us that such is the pressure on space that 15 people had slept there the previous night. She had fled south from the air strikes on Saada, one of which had killed her husband and injured three of her children.

In another tent 30-year-old Nouria Hamood Awbali told us how she and her five children got caught up in the fighting between Houthi soldiers and the Saudis in her northern village.

“There were so many aeroplanes,” she said. “My daughter Naria came to me and said: ‘The skies are on fire.'”

Then the first air strike hit and 13-year-old Naria received deep shrapnel wounds in her arm. Naria was in deep pain, and regularly suffers convulsions of terror when aircraft go overhead. They are so serious that she needs to be forcibly held down. Her right hand is withered.

The family ran from village to village but everywhere there were air strikes. Nouria Awbali was heavily pregnant when the fighting started and gave birth to her daughter Regan as they were escaping from a new wave of Saudi attacks.

She told us that her first action after the birth was to leap on top of the baby to protect her as a bomb exploded nearby.

“We were caught in the middle,” she said. “One day they would tell us that it was King Salman hitting us. The next day it was the Houthis and Saleh. They were all hitting us.”

Packs of wild dogs roam devastated ruins

When we reached Saada in the late afternoon we saw the full scale of the destruction. Almost every building in the main street has been bombed while some of the residential suburbs of Saada have been damaged beyond repair.

One example was the Rahban, a complex of ancient multi-storey mud houses very typical of northern Yemen and dating back to ancient times. Before the war, thousands of people would have lived in the Rahban.

It was now badly damaged and empty. It was hard to imagine anyone ever returning. The inhabitants are either dead or living precarious lives as internally displaced persons.

The Saudis had also targeted Saada’s spiritual centre, the mosque of Imam al-Hadi.

Though still standing, the ancient building is damaged. We were refused permission to see it because we were told it is structurally unsound as a result of the strikes.

However the square outside the mosque – some of whose houses are said to date back 1,000 years or more – is now reduced to rubble and home only to a pack of wild dogs.

The horror of the ‘double tap’ air strike

In Saada, Saudi Arabia had adopted the murderous tactic of so-called “double tap” air strikes.

Dr Mohamad Hajar, the head of logistics at the Republic Hospital in Saada, described how two ambulance men had rushed to the scene of a Saudi bombing in order to pull four wounded civilians out of the rubble. They had put them into the back of the ambulance and were setting off for the hospital when the Saudis returned with a second and far more deadly attack.

It killed both ambulance men along with the four wounded civilians. In all 26 people died in this Saudi air strike, he told us. We were told that all of them had come to the scene to help the wounded.

Amat al Kareem, the widow of one of the dead ambulance men, Abdul Malik, told us: “We spent two days looking for bodies but there was nothing left. We could find no trace. There was nothing to bury.”

She said that Malik had been injured many times by air strikes and that the hospital had urged him to retire but “he wouldn’t give it up”. She remembered how “he would tell me that if he went out and saved people’s lives, God would protect me and the children regardless of what happened to him.”

Kareem sobbed convulsively and clutched her two children as she remembered her dead husband: “There is no life without him. The house has no life. We need him. His children need him.”

We asked her what she thought of the Saudis. She replied: “They are killing women and children in their homes. Where else can we go to be safe if they are bombing them in our homes?”

The bombs that lie undiscovered, then kill

Despite the ceasefire, Saada was also feeling the murderous effects of cluster bombs left behind by earlier bombing raids. These are uniquely dangerous because they are designed to explode in mid-air, scattering dozens of smaller devices. They can then lie around for months or years after a strike, posing a threat to unwary civilians and – in particular – children.

Just a few days before our visit 12-year-old Abdul Razzaq and three companions were returning from school to the family farm when they picked up a cluster bomb.

It exploded, killing Razzaq and wounding one of the others. We went to the farm but his parents were too upset to speak to us. “What is the point?” they asked. “It will not bring him back.”

The cluster bomb which killed Razzaq was manufactured in Brazil.

But our Houthi guides took us to a rocky hillside outside the village of Rezamat where, they said, four British-made cluster bombs had landed in an attack last year.

Local man Salah Hamoud told us that a farmer’s boy, Ahmed, was hurt in the attack. The debris was still scattered around.

Hamoud said that the bombs had fallen near a disused checkpoint. “There were no military around here, just farmers.”

We could not verify the story, but an Amnesty International research team which visited Yemen in April reported finding unexploded British-made cluster munitions in the country.

Houthis ‘used refugees as human shields’: UN

We were unable, with our official minders, to cross the lines into areas outside Houthi control and hear testimony of the destruction and abuses carried out by Houthi fighters.

In any case, it is too dangerous to travel to areas, such as the besieged city of Taiz in south-western Yemen, where some of the worst alleged Houthi abuses have been committed.

There is abundant evidence of Houthi atrocities. Earlier this year a UN panel, leaked to the press, accused Houthi rebel forces of committing a “systematic pattern of attacks resulting in violations of the principles of distinction, proportionality and precaution, including carrying out targeted shelling and indiscriminately aimed rocket attacks, destroying homes, damaging hospitals and killing and injuring many civilians.”

The panel report also accused Houthi rebels of having used African migrants and refugees as human shields, and blocking access to food, water and medical supplies in Taiz. For more than a year, the city has been relying on young boys and women carrying food and life-saving supplies on the backs of donkeys via a long and treacherous journey.

In Taiz, both the Houthis and the resistance fighting against them have fought with no regard for civilians, shelling homes, hospitals, schools and heritage sites.

Human rights organisations such as HRW and Amnesty have also documented international humanitarian law violations by the Houthis, such as the recruitment of child soldiers (who were plentifully in evidence on the streets of Houthi-controlled cities), the imprisonment of journalists and activists as well as the shelling of civilian areas in Taiz, Aden and elsewhere.

But according to a UN report released in April the Saudi-led bombing campaign has been responsible for the majority of civilian casualties in Yemen.

How the West is complicit in the horror

Britain, France and the United States have supported the Saudi coalition and its attacks on Yemen targets since the start of the war.

Last week, US Secretary of State John Kerry and British Middle East minister Tobias Ellwood were in Jeddah for talks on Yemen with officials including Saudi foreign minister Adel Al Jubeir, his UAE counterpart Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan, and the UN’s special envoy for Yemen Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed.

Calling for the war to end “as quickly as possible”, Kerry laid out proposals to bring the warring parties back to the negotiating table. Those proposals included calls on the Houthis to withdraw from Sanaa and to give up their heavy weaponry.

Britain, meanwhile, has not merely continued to make arms sales to Saudi Arabia and its partners. It has supported the UN Security Council resolution backing a Saudi blockade, which has helped to inflict a humanitarian calamity on Yemen, although Britain has tried to persuade the Saudis to allow much-needed aid supplies through.

Britain has also provided the Saudis with intelligence and logistical support.

According to Adel al-Jubeir, the Saudi foreign minister, American and British advisers are at the heart of the Saudi bombing operation. He told journalists in January that “we have British officials and American officials and officers from other countries in our command and control centre. They know what the target list is, and they have a sense of what it is that we are doing and what we are not doing.”

Jubeir added that foreign officers did not play any role in choosing targets: “We pick the targets, they don’t. I don’t know technically exactly what part of the process they are in, but I do know they are aware of the target lists.”

The Saudi foreign minister pointed to the presence of these foreign observers as “evidence that we have nothing to hide.”

Earlier in August, a US Navy spokesman in Bahrain told Reuters that the US military would be withdrawing most of its personnel who were coordinating with the Saudi-led air campaign. Lieutenant Ian McConnaughey said the reduction – from a peak of about 45 staff members to fewer than five – was not related to international concerns about growing civilian casualties.

A Foreign Office spokeswoman told us that “the UK is not a member of the Saudi Arabian-led coalition. British personnel are not involved in carrying out strikes, directing or conducting operations in Yemen or selecting targets, and are not involved in the Saudi targeted decision-making process.”

Perhaps most crucially of all, Britain and the United States have provided Saudi Arabia with diplomatic cover. Last year, Britain and the United States helped to block a Dutch initiative at the UN Human Rights Council for an independent investigation into violations of international humanitarian law.

Adel al Jubeir, Saudi Foreign Minister

‘We have British officials and American officials and officers from other countries in our command and control centre’

When we put this to the Foreign Office, a spokeswoman told us that “the UK’s priority was to secure cross-regional agreement on a text that strengthens human rights in Yemen as we urge all parties to find a solution to the crisis.”

The then-British foreign secretary Philip Hammond (who last month became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the wake of the Brexit vote) has repeatedly refused to accept that the Saudis have done anything wrong.

In November 2015 he told parliament that “there is no evidence that IHL [international humanitarian law] has been breached.” The following February the foreign secretary went further still, stating that Britain had “assessed that there has not been a breach of IHL by the coalition,” an assertion which he repeated on three separate occasions.

Elwood has taken the defence of Saudi Arabia a stage further than Philip Hammond by claiming that the “media-savvy” Houthis may have fabricated evidence of Saudi air strikes.

He suggested to MPs that the Houthis “who are very media-savvy in such a situation, are using their own artillery pieces deliberately, targeting individual areas where the people are not loyal to them, to give the impression that there have been air attacks.”

Like Hammond, Elwood has claimed that Britain conducted its own assessment into breaches of IHL. However, the Foreign Office now claims that that these systematic misrepresentations were “mistakes”.

This assertion does not ring true.

The Foreign Office is famed for precision in its reporting and does not have a record of making “mistakes” of this kind. Bear in mind that false statements were not made once, but repeated on numerous occasions.

Britain has been protecting Saudi Arabia and its allies as it fights a murderous and illegal war in Yemen. Saudi is a longstanding British ally, a vital buyer of British arms and key producer of oil.

So there is every reason to assume that Britain has a strong reason to ignore or to underplay evidence that the Saudi-led coalition has been in breach of IHL, which gives very strong protections to civilians caught up in fighting, and bans the targeting of civilian institutions like schools and hospitals.

There is no doubt that the Saudis are prepared to use their muscle. In April the UN placed the Saudi-led coalition on a list of country’s violating children’s rights, following a UN report citing the killing of children in the Yemen conflict. Only days later the UN reversed the decision following allegations of Saudi pressure.

To sum up, Ellwood and other Foreign Office ministers had very strong motives to protect Saudi Arabia and give false information to Parliament.

Certainly the Houthis have carried out many atrocities. But such conduct makes Britain complicit with what looks very much like a campaign of war crimes and mass murder.

Elwood could only get away with his false statements because few care about the massive humanitarian crisis happening in Yemen.

Although thousands of Yemenis have become refugees, very few have reached the soil of Europe to attract the attention of media or politicians.

They have almost no hope of doing so. To escape by land, refugees would have to traverse hundreds of miles of desert controlled by Saudi Arabia, the country bombing them. To escape by sea they must evade the naval blockade, only to land on the unfriendly coast of Eritrea.

This means that, although their situation is almost as desperate as that of the victims of Syria’s war, the Yemenis are invisible to Europe. That is not good enough. A calamity, aided and abetted in the West, is unfolding in Yemen, and it is time the world woke up to that fact.