Special Report: The wonks who sold Washington on South Sudan

11 July 2012

In the mid-1980s, a small band of policy wonks began convening for lunch in the back corner of a dimly lit Italian bistro in the U.S. capital.

After ordering beers, they would get down to business: how to win independence for southern Sudan, a war-torn place most American politicians had never heard of.

They called themselves the Council and gave each other clannish nicknames: the Emperor, the Deputy Emperor, the Spear Carrier. The unlikely fellowship included an Ethiopian refugee to America, an English-lit professor and a former Carter administration official who once sported a ponytail.

The Council is little known in Washington or in Africa itself. But its quiet cajoling over nearly three decades helped South Sudan win its independence one year ago this week.

Across successive U.S. administrations, they smoothed the path of southern Sudanese rebels in Washington, influenced legislation in Congress, and used their positions to shape foreign policy in favor of Sudan’s southern rebels, often with scant regard for U.S. government protocol.

“We never controlled anything, but we always did try to influence things in the way we thought most benefited the people of South Sudan,” said Roger Winter, now an honorary adviser to the South Sudan government and one of the group’s original members, who dubbed himself the Spear Carrier.

The story of the Council has not been told before. For a Reuters series chronicling the first year in the life of South Sudan, the group’s main members spoke for the first time about how they came together and what they tried to achieve. They pinpointed key moments when peace could have slipped away. Some expressed disappointment at the compromises America made to broker the creation of South Sudan. One idea shines through: Independence was far from inevitable.

“I actually think it was a miracle we got something,” said Winter.

Nationhood has many midwives. South Sudan is primarily the creation of its own people. It was southern Sudanese leaders who fought for autonomy, and more than two million southern Sudanese who paid for that freedom with their lives.

President George W. Bush, who set out to end Africa’s longest-running civil war, also played a big role, as did modern-day abolitionists, religious groups, human rights organizations and members of the U.S. Congress.

But the most persistent outside force in the creation of the world’s newest state was the tightly knit group, never numbering more than seven people, which in the era before email began gathering regularly at Otello, a restaurant near Washington’s DuPont Circle.

A CHARISMATIC REBEL

In 1978, Brian D’Silva, a young student in agricultural economics, began pursuing a doctorate at Iowa State University. There, he studied alongside an intensely charismatic southern Sudanese man named John Garang, who had begun dreaming of a democratic Sudan.

After graduation, D’Silva went with Garang to Sudan to teach at the University of Khartoum. An uneasy peace held between Sudan’s predominantly Arab Islamic north and largely Christian south. The divide stemmed from colonial times, when Britain encouraged Christian missionaries to evangelize the south. The British considered splitting the country in two, but ultimately handed a unified Sudan to a small Arab elite in Khartoum, who tried to impose Islamic law throughout the country.

A 1972 agreement had given southerners semi-autonomy. That fragile deal began unraveling in 1979 after Chevron discovered oil in the south; the north did not want to lose control over the newly found riches.

D’Silva returned to the United States in 1980 to work for the U.S. Agency for International Development. Three years later, his old schoolmate Garang, a conscript in the Sudanese army, led a mutiny of southern Sudanese soldiers. His group would become the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement (SPLM), which led the fight for southern autonomy.

Roger Winter visited Sudan in 1981 for a non-governmental outfit called the U.S. Committee for Refugees. Upon his return, the former Carter administration official sought out Sudanese who were based in Washington. Key among them was respected legal scholar Francis Deng, a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

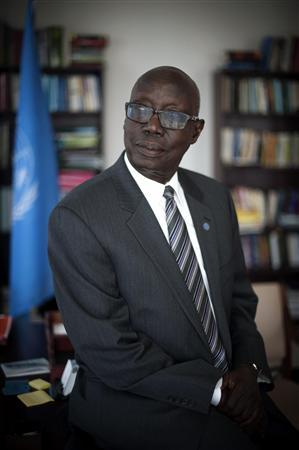

“A man with a ponytail came to see me,” recalled Deng, who is now the U.N. Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide.

Deng hails from Abyei, a fertile area straddling north and south Sudan. He thought Winter must be some “wealthy hippie-type” who wanted to give money to the rebels. When Winter explained that the best he could do was disseminate information, Deng suggested that the American public needed first-hand accounts of people affected by the war. He called a cousin in the rebel movement to ensure that on future visits, Winter would have access to all the so-called liberated areas – the parts of Sudan held by the rebels – where he could gather direct testimony on the impact of the war.

By the mid-1980s, these three future Council members – D’Silva, Deng and Winter – were working in the United States as proxies for John Garang. Over six feet tall and more than 200 pounds, the rebel leader had a laugh – and a personality – that filled a room.

“You meet Dr. John, you get converted,” said Winter, who first met Garang in 1986.

The three men quickly discovered the size of the task ahead of them. In 1987, D’Silva tried to bring a delegation from the SPLM to meet officials in Washington. But standard procedure at Foggy Bottom was to maintain relations with the recognized Sudanese government in Khartoum and ignore the rebel movement. D’Silva received a phone call from an official instructing him that no meetings should be arranged on any government-owned or -leased property.

ENTER “THE EMPEROR”

According to Deng, many in Washington associated the rebels with the Soviet-backed government in neighboring Ethiopia, leaving the SPLM on the wrong side of the Cold War. “It took a lot of hard work to remove the prejudice against John Garang,” Deng said.

As D’Silva, Winter and Deng tried to get the southern rebels through doors in Washington, a wayward college graduate in search of a cause was traveling in the Horn of Africa. By the early 1990s, John Prendergast had decided his calling was to help win better U.S. policies for Africa.

At the time, the circle of people in Washington who cared about the Horn of Africa was small. Prendergast soon ran into Winter, and the pair began briefing journalists, urging them to cover the conflict and putting them in contact with the rebels.

Human rights campaigning was very different from today. The idea of Western groups advocating in a coordinated way on behalf of foreign causes – as they had during the British-led anti-slavery campaigns in Belgian Congo more than a century before – had only recently been rekindled by the likes of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

For the few Americans who had heard of Sudan at all, “the south was a black hole,” said Winter, the refugee-rights organizer.

It was about this time that the Council’s future Emperor made his entrance. Ted Dagne was a 14-year-old Ethiopian in 1974 when a Soviet-backed military junta seized power. Dagne’s older sister, a student leader, was among the first to be executed by the new government.

“After that, there was a (target) on our family,” said Dagne, drawing a cross in the air.

By the time Dagne was 16, both he and his older brother had been imprisoned and tortured. Dagne was subsequently released, but his brother was executed and Dagne’s own prospects for survival looked slim. One morning he donned his sister’s T-shirt and his brother’s jeans and shoes, keepsakes for an unknown future, and told his parents he was going out for groceries. It was the last time he saw them.

With the help of a Somali man who pretended to be his father, Dagne crossed the border into Somalia. Eventually he reached Djibouti, and subsequently joined a generation of people fleeing communist lands who were granted asylum in the United States.

Dagne got through college by working two jobs – answering phones from 11 p.m. to 6 a.m. and an afternoon shift at a Lincoln Memorial souvenir kiosk. By 1989 he had earned a masters degree, acquired U.S. citizenship and was working on African affairs at the Congressional Research Service, the non-partisan policy-analysis arm of the U.S. legislature.

AN EYE-OPENING VISIT

That year, Winter took two members of Congress to meet Garang on one of his visits to rebel-held areas of Sudan. The trip had a big impact. One of the visitors, Viriginia Republican Frank Wolf, said he still remembers a question put to him by a Dinka woman named Rebecca.

“She said to me, ‘Why is it that you people in the West are very interested in the whales but no one seems to be interested in us?'” he recalled. “It was an eye-opener, and I became very sympathetic toward the southerners.”

After that, D’Silva, Deng, and Winter finally managed to get a delegation led by Garang on an official visit to Washington.

Wanting to ensure the group from his homeland made a good impression, Manute Bol, the 7-foot, 7-inch sensation for the Golden State Warriors basketball team, offered to hire a limousine to take Garang’s delegation to Capitol Hill. Winter told them this was a bad idea.

“I explained to them, you can’t go to the Capitol building in this and then go in and talk about starving people!” Winter recalled. The visitors switched to an old bus that blew out gobs of black smoke as it sputtered to Congress.

It was on that visit to Washington that Dagne met Garang for the first time. More than any other member of the Council, Dagne formed an intense friendship with the rebel leader. There were periods in the years ahead in which they spoke by phone every day, Dagne says.

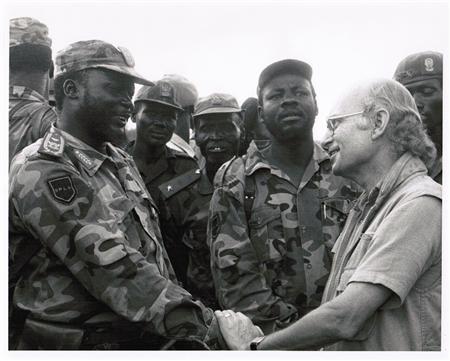

John Garang (L) shakes hands with Roger Winter, now an honorary adviser to the South Sudan government and one of the Council’s original members, in this undated image taken in Sudan and provided to Reuters by Roger Winter. Nationhood has many midwives. South Sudan is primarily the creation of its own people. It was southern Sudanese leaders who fought for autonomy, and more than two million southern Sudanese who paid for that freedom with their lives. U.S. President George W. Bush, who set out to end Africa’s Longest-running civil war, also played a big role, as did modern-day abolitionists, religious groups, human rights organizations and members of the U.S. Congress. But the most persistent outside force in the creation of the world’s newest state was the Council, a tightly knit group never numbering more than seven people, which in the era before email, began gathering regularly at Otello, a restaurant near Washington’s DuPont Circle.

By the early 1990s, the group’s work was starting to pay off. Dagne was seconded from the Congressional Research Service to the House of Representatives Subcommittee on Africa, where he began to build allies for the southern Sudanese cause.

Congressional staffers are supposed to be neutral, but it was an open secret that Dagne’s allegiance lay with the southerners. “Ted was very suspicious of the Sudan government, and so I became very suspicious,” said former Democratic Senator Harry Johnston, who headed the subcommittee.

“I pushed the envelope quite a lot,” Dagne acknowledges.

In 1993, for instance, Dagne drafted a congressional resolution stating that southern Sudanese had the right to self-determination. He passed his draft to Johnston, who reviewed it and then presented it to his colleagues in Congress. The resolution was not binding, but it passed unanimously. It was the first time any part of the U.S. government had recognized the right of the southerners to determine their own relationship to the Sudanese government.

By the mid-nineties, five men – Dagne, Deng, D’Silva, Prendergast and Winter – were meeting regularly at Otello’s. Prendergast had been nicknamed the Council Member in Waiting because he liked to challenge the Emperor. Deng was referred to as the Diplomat, marking him as the least strident of the group. D’Silva, the most serious among them, went without a nickname.

The group was united by a respect for Garang. The men acknowledge that his SPLM fighters committed horrific crimes during the war, and say they often had highly critical conversations with Garang. But they say they never doubted that they backed the right side.

“You have these well-trained guys in Khartoum who are murderers and never keep an agreement,” said Winter. “How do you treat them equally?”

MODERN-DAY ABOLITIONISTS

Crises in Somalia and Rwanda were absorbing most of America’s attention in Africa. But the southern Sudanese cause soon got a boost from an unlikely quarter.

In 1995, Christian Solidarity International initiated a controversial program in Sudan called slave redemption. The Zurich-based human-rights organization began paying slave traders for the freedom of southerners captured in raids by government-backed militias from the north. Christian Solidarity took journalists and pastors from the black evangelical community along on their missions, and stories of modern-day slavery filtered into church congregations and the U.S. media.

The group drew fire for fueling a market for slavery, but it had a big impact in the United States. American schoolchildren began raising money to free slaves, and members of Congress started getting letters from their constituents. “Americans are divided on just about every issue imaginable, but we are an abolitionist nation,” said Charles Jacobs, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Group, which led the U.S.-based outcry.

Dagne’s network of southern Sudan allies in Congress solidified. He organized trips into SPLM-held areas for bipartisan delegations, including Tennessee Republican Sen. Bill Frist and the late New Jersey Democratic Rep. Donald Payne.

Seeing the human impact of the war firsthand, the lawmakers grew as skeptical of Khartoum as the Council was. For Frist, a surgeon, a key moment was seeing personnel at a field hospital in southern Sudan having to flee a government bombing raid to nearby caves during the middle of an operation.

“Why, I asked myself?” Frist recalled. “No answer except the government in Khartoum’s goal to create terror.”

For meaningful change, however, the executive branch needed to get on board. This was tough as long as the State Department focused on maintaining a working relationship with Khartoum.

In 1993, though, the United States linked a car bomb at the World Trade Center in New York to Osama bin Laden, a Saudi Islamic fundamentalist living in Sudan. Khartoum was added to the State Department list of state sponsors of terrorism.

A chance encounter at a Princeton University conference on Somalia provided the Council its next break.

Among the speakers was Susan Rice, a young Rhodes Scholar who was gaining influence in the State Department as the senior director of African affairs. Rice and Dagne took the train back to Washington together, talking U.S. policy on Africa for the four-hour journey. Rice soon became an informal member of the Council, dropping in occasionally for lunches at Otello. Rice, currently the U.S. ambassador to the U.N., declined to comment for this article.

Prendergast, who also met Rice at the conference, applied to work for her. In his job interview, he says, he told her that Khartoum was “too deformed to be reformed,” a view that had long been espoused by the southern rebels. Rice hired him.

A LITERARY POLEMICIST

Rice successfully urged the Clinton administration to place comprehensive sanctions on Sudan, prohibiting any U.S. individual or corporation from doing business there. This shift brought the official U.S. position closer to the Council’s.

By the late 1990s, Washington was not just providing humanitarian assistance to the southern Sudanese. It was also giving leadership missions and training, as well as $20 million of surplus military equipment to Uganda, Ethiopia and Eritrea, who all supported the southern rebels. Prendergast said the idea was to help states in the region to change the regime. “It was up to them, not us,” he said in an interview.

But the regime was hard to shift. Thanks to a pipeline built by the Chinese linking the southern oil fields to the Red Sea, Sudan began exporting oil in 1999. Now Khartoum had a new source of revenue to fund its fighting.

The Council’s Deputy Emperor, Eric Reeves, joined in 2001. Reeves was a professor of English literature at Smith, a small college in Western Massachusetts. He had no background in Sudan. But after reading about the humanitarian conditions in the south and attending a lecture Winter gave at the college, Reeves became the Council’s most prolific writer. He published hundreds of opinion pieces and blogged detailed reports brimming with moral outrage against Khartoum.

When George W. Bush took office in 2001, Rice and Prendergast left the State Department and joined think tanks. That left only USAID policy adviser D’Silva and congressional researcher Dagne on the inside track. Suddenly, though, the Council’s cause became a White House cause.

On the second day of his presidency, Bush directed senior staff to focus on bringing an end to the war in Sudan. Bush declined to comment on what drove him to home in on Sudan. But a pillar of his support base, evangelical Christians, was imploring him to take up the cause. They had long been concerned about the persecution of Christians in southern Sudan.

One influential evangelical, the Rev. Franklin Graham, recalls pushing the future president to focus on Sudan during a breakfast meeting they had in Florida two days before the presidential election.

At the urging of religious groups, Bush also appointed former senator and Episcopalian minister John Danforth to be his envoy, tasking him with helping to unlock ongoing negotiations between north and south.

Evangelical groups suddenly found journalists turning up on the doorstep. “People wanted to hear what we wanted to say,” said Deborah Fikes, spokeswoman for the Midland Ministerial Alliance, based in Bush’s hometown of Midland, Texas.

Fikes started working with the Sudan embassy and went to Khartoum to meet those in the government she believed were moderates. That didn’t impress the Council, who accused her of naiveté. “She didn’t know what the hell she was doing,” said Reeves.

Fikes dismisses the criticism. “I didn’t have a career or an agenda. When you look at Christ, he was misunderstood,” she said.

“DAMNED IF WE DO?”

After his time in the Carter administration, Winter had vowed never to work in government again, preferring the less bureaucratic non-government sector. But USAID Administrator Andrew Natsios convinced him that Bush was going to make peace in Sudan a priority. Winter agreed to return to government. With his new role as an adviser to Danforth, the Council was back at the center of Sudan policy.

As with Dagne, it was an open secret that Winter was biased. Danforth says he asked for Winter’s help because of his detailed knowledge. Winter himself felt tension with many of the diplomats he was now working alongside. “The State Department was used to working with Khartoum,” Winter said.

Progress came that summer, when Khartoum’s chargé d’affaires in Washington, Ahmed Khidir, flew to Danforth’s home in St Louis, Missouri. Khidir had just one question, Danforth recalls: “Are we damned if we do and damned if we don’t?” In other words, if Khartoum agreed to peace, would it still be a pariah to the U.S. government?

The answer mattered. Ever since the rulers in Khartoum had taken power in a 1989 coup, their ability to maintain control depended greatly on patronage networks. Because the United States had effectively black-listed Sudan, Khartoum had to rely on loans from non-Western nations and revenue from the south’s oil fields to fund these networks.

To sign a pact in which they risked losing the oil-rich south, northern leaders needed an alternative source of income. Normalizing relations with Washington would be a sure pathway back to the international financial system.

After consulting with Bush, Danforth told Khidir that Washington looked forward to normalizing ties. “That was an important message,” Danforth said in an interview. Khidir couldn’t be reached for comment.

The biggest breakthrough, however, came not as the result of diplomacy or advocacy, but of Al Qaeda’s attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001.

When Bush told the world that Washington would “pursue nations that provide aid or safe haven to terrorism,” the U.S. relationship with Khartoum changed overnight. Sudan had expelled Al Qaeda leader bin Laden in 1996, but it worried it might be a U.S. target. Washington suddenly found itself with enormous leverage over Khartoum, which the Bush administration used to push for a peace agreement.

Almost all the key issues that would end up in a landmark 2005 peace deal between Khartoum and the SPLM were agreed in the first five months of 2002. Most surprisingly, Khartoum agreed to let the southerners hold a referendum on whether to remain part of Sudan.

By 2003, though, progress stalled. Reports of U.S. overstretch in Iraq and Afghanistan diminished Khartoum’s fears of becoming a future military target. And the U.S. government approach to Khartoum started to fracture.

The CIA had issued glowing reports about Sudan’s cooperation in the “War on Terror” and supported Bush’s promise of normalized relations. On the other hand, events in Sudan took on a life of their own.

As it became clear that southerners were getting a new deal, people in Darfur, in west Sudan, wanted one, too. The civil war had been framed as a north-south or Muslim-Christian conflict. The truth was that southerners were far from the only group suffering under Khartoum. Other marginalized groups included the religiously diverse populace of the Nuba Mountains and mixed northern-southern populations in the Blue Nile and Abyei.

As the Darfuri rebellion escalated, Khartoum moved to crush it. The Council immediately saw the parallels between Khartoum’s response and previous atrocities in the south. But shifting the U.S. focus to Darfur could jeopardize the peace agreement for the south.

Dagne consulted Garang, who encouraged him to introduce the Darfuri cause to the U.S. lawmakers backing the southerners. The Council stepped in; over the coming years they would be among the most crucial actors in cementing the previously unknown Darfur region in the imagination of the American public.

Prendergast, at the time working at an independent research group, became a key player in the founding of the Save Darfur movement. He spent weeks at a time talking about Darfur on college campuses and working with actor George Clooney, who became an advocate for the cause. Reeves and Rice, then a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, wrote op-ed pieces. At USAID, Winter and D’Silva organized visits for State Department officials so they could see the violence firsthand. And after interviewing Darfuri refugees, Dagne worked with Rep. Payne on a resolution calling the atrocities genocide.

Dagne was by now an expert at getting his congressional allies to insert pro-southern provisions into sure-to-pass bills on unrelated topics. Using this approach he had succeeded in exempting rebel-held areas of southern Sudan from U.S. sanctions.

His Darfur genocide resolution, though, needed no such maneuver. Growing public outrage ensured it passed the House and Senate unanimously.

PEACE – AND A BLOW

In January 2005, as fighting in Darfur continued, Khartoum finally concluded a Comprehensive Peace Agreement with the south. Garang invited Dagne and Winter to dinner at his home in Nairobi, Kenya, to celebrate.

Seven months later, the south Sudanese leader died in a helicopter crash. Garang’s death was a huge blow to the south Sudanese project, but the Council rallied around his successor.

Salva Kiir, who had spent his career on the battlefield, is as understated as Garang was garrulous. Before Kiir’s first meeting with Bush, the Council gathered in his Washington hotel suite for an informal briefing, just as they had been doing since Garang’s first visit to Capitol Hill.

After the peace pact was signed, Winter retired from government. D’Silva remained at USAID and Dagne at the Congressional Research Service, while Prendergast founded his own advocacy organization. Rice, after Obama won office, joined the new administration as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.

But the momentum ebbed as fractures opened up in the new administration.

Retired Air Force General Scott Gration, the president’s new envoy to Sudan, wanted closer engagement with Khartoum. Gration didn’t respond to requests for comment.

But in interviews in 2009, he argued that without resetting the relationship, Khartoum had no incentive to let the southerners vote on independence. He thought that making sure the independence referendum happened on time should be the overriding objective. Rice maintained vocal skepticism, believing that Khartoum’s treatment of troubled areas outside the south, like Darfur, warranted continuing condemnation.

A lengthy and acrimonious policy review ran through late 2009. In the end, it recommended that Darfur, north-south peace, and counter-terrorism cooperation should all be given equal priority. But disagreement around the details meant there was no consensus on how to pursue all three objectives. The first 18 months of Obama’s term slipped away in a bureaucratic stalemate.

Finally, in the summer of 2010, Obama called his Sudan team into the Oval Office. The president said he would not allow a return to bloodshed between north and south, according to Denis McDonough, chief of staff at the National Security Council at the time.

SHOWDOWN WITH BIDEN

Momentum returned. Vice President Joe Biden, due in South Africa for the World Cup, was tasked with urging leaders across Africa that the independence referendum must go ahead. Some African countries feared that southern independence would establish a precedent for secessionist movements in their own states.

Meanwhile, Sudanese preparations for the referendum had stalled. Khartoum and Juba couldn’t agree on the makeup of a steering group handling the logistics of the vote, and Khartoum was dragging its feet in releasing funds promised for the poll. The south had been urging Washington to push Khartoum to fulfill its promises.

At a meeting in Nairobi, Biden told Kiir the South Sudanese themselves had to make sure the vote happened.

“‘I don’t care about what Khartoum is or is not doing,'” he said, according to Cameron Hudson, who attended as a member of the National Security Council. “‘We can’t want this more than you.'” Kiir’s office declined to comment on the meeting.

Throughout the fall of 2010, the National Security Council’s McDonough chaired meetings of a dozen Sudan policymakers every evening, often to midnight. They debated what incentives to offer Khartoum in exchange for letting the south go.

One important call was over what the north needed to do to trigger these incentives: Was holding the referendum enough? Or should the rewards be tied to the completion of other outstanding issues, such as border demarcation and oil flow?

Ultimately, the group concluded that they could not force the parties to agree on anything beyond holding the referendum. The U.S. decided to push for the vote to go ahead as scheduled. It began on January 9, 2011. The final tally showed that 98.8 percent of voters chose independence for southern Sudan.

Speaking before the U.N. Security Council six months later, on the day South Sudan joined the world community, Rice promised that the United States would remain a “steadfast friend.” Washington pledged $370.8 million in aid for the new country in the six months following independence alone.

OFF TO JUBA

The unresolved diplomatic issues have come back to haunt the region.

In January, Kiir shut down the southern oil industry, accusing Khartoum of having stolen 1.7 million barrels of South Sudan’s oil from a cross-border pipeline. Khartoum said it only confiscated what it was owed in pipeline fees. Other unfinished business – the border, and the fate of regions such as Abyei and the Nuba Mountains – has sparked new violence.

Still, the current U.S. envoy to Sudan, Princeton Lyman, argues that even in hindsight, it was right for the U.S. to push for the referendum to be held on time.

Members of the Council have mixed views on the legacy of the peace agreement.

Prendergast, Deng and Reeves – none of whom were in government when the agreement was created – are pessimistic, believing that other troubled areas in Sudan should have been more seriously attended to.

D’Silva wonders whether the agreement would have been better implemented had Garang survived.

Winter and Dagne – who were closest to the creation of the final pact – are more sanguine, saying the independence of the south alone justifies the agreement. Previously, the north-south clash was a domestic dispute which the world could ignore. Now it is a conflict between two states, and the south has its own army to defend itself.

“All the other issues are minor once you have your sovereignty,” Dagne said.

One evening in January, Dagne headed to Dulles International Airport outside Washington to catch a flight to Juba. He had left his Congress job and was off to take up a role as special adviser to South Sudan’s President Kiir. Leaving behind his family and a secure U.S. government position, he was returning to the continent he left 31 years earlier.

On his iPhone, Dagne carries a recording of a message Garang left him less than 24 hours before he died. “Hi, Nephew, this is Uncle,” it begins.

Dagne scrolled through farewell messages from Council members.

“South Sudan could not be more fortunate,” wrote Reeves. “I salute you… you are…the Emperor.”

(Editing by Eddie Evans and Simon Robinson)