Our Article about Ebesh Hatun of Iran, a Ruling Woman in Islam on MintPress

Great Women In Islamic History: Ebesh Hatun Of Iran

Follow @promosaik_ @promosaik_

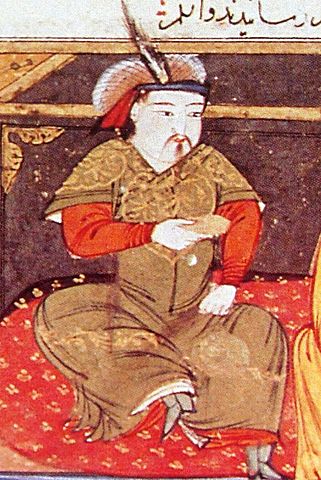

painting of Hulagu Khan by Persian historian Rashid al-Din. Hulagu Khan

rides on horseback with

his mounted army, accompanied by a hunting dog

and footmen. Like many leaders of the era,

Ebesh Hatun held power by

swearing allegiance to a Mongol ruler. (Wikimedia /

Bibliothèque

nationale de France).

Other selections from this series: Introduction: A Forgotten Study Of Female Political Power In Muslim History, Türkan Hatun of Iran, and Padishah Hatun of Iran.

Ebesh Hatun Of The Fars Princedom Of Salgur

Ebesh Hatun (also known as Abish Hatun) was a Turkish woman renowned

as the recognized sovereign of the State of Salgur, in the Fars province

in the second half of the 13th century (1283-1287).

A brief history of Salgur

In this chapter of her book, historian Bahriye Üçok briefly

introduces the founding history of this state to make us understand

under which condition a woman was able to come to power.

illustration of Ebesh Hatun in a hat and flowing, button-up shirt with

long flowing dark hair. (Illustration from Dr. Bahriye Üçok’s “Female

Sovereigns in Islamic States.”)

The name of the princedom originates from Salgur, who was the leader

of one of the Turcoman communities and then became chamberlain to Tuqrul

of the Iraq Seljuks. One of Salgur’s grandsons, Sungur bin Mevdut, rose

against the Seljuks in 1147-8 following the murder of an emir related

to him, and proclaimed independence in the province of Fars.

So Salgur became independent and Shiraz its capital. However, this

independence was not to last for long. The Salgurs started to pay taxes

at first to the Seljuks of Iraq, and later, in the time of Atabey I Sa’d

to the Harezmshah.

The sixth ruler, Ebubekir, feeling himself at risk by the Mongols,

announced his allegiance to Hakan Ögedey and Ilhan Hulagu in 1256 by

paying taxes to them. Under Ebubekir, the Salgurs prospered and expanded

until his death. His son Sa’d II followed him.

After his death, the people of Shiraz put his young son Muhammed on the throne. Türkan Hatun,

his mother, acted as regent. This is one of various examples we find in

Üçok’s book: indeed, many female rulers got the chance to rule because

the male successors were too young or not competent enough. To protect

herself from the Mongols, Türkân Hatun sent letters declaring her

allegiance to Hulagu, together with gifts befitting a prince, and

received from him, written to her son’s name, a decree of formal

recognition.

Türkân Hatun, with the help of her viziers Nizamüddîn Ebubekir and

Shemsüddîn, administered the country in the name of her son Muhammed

until he died in 1261-2. She offered the throne to Muhammed Shah, the

son of Muhammed’s uncle, Salgur Shah, a man of courage but lacking

statesmanlike qualities and a drunkard. Muhammed Shah had gained the

favour of Hulagu because of the great courage he had shown when fighting

near Baghdad. Türkân Hatun hoped that his courage would bring stability

to the country, but this was not the case.

So Türkan Hatun conspired against him and in the end put him to

death. Again we see how women use intrigues and chess games to maintain

their power, by contemporaneously finding diplomatic adjustments with

their male supporters.

The Shol Emirs reached an agreement with Türkân Hatun to bring Seljuk

Shah to the throne. Selçuk Shah thereupon increased his influence still

further by marrying Türkân Hatun, a similar story we have already seen

in Egypt with the slave Aybek marrying the ruler Shajarat ad-Durr.

Enter Ebesh Hatun

For, since the Mongol prince Mengü Timur was betrothed to one of

Türkân Hatun’s daughters, Ebesh Hatun, Türkân Hatun was related to the

Mongols through her daughter. Nevertheless, this relationship was not

sufficient to save her from destruction at the orders of her drunken

husband during the course of a night of festivities. Seljuk Shah had

Türkân killed, either in order to completely destroy the influence she

still retained from the time of her regency, or to avenge his brother.

14th-century illustration of Hulagu Khan by Persian historian Rashid

al-Din. Hulagu sits on a red carpet in royal clothes and a feathered

cap. (Wikimedia)

It is very important to mention that Ebesh’s rule was supported by

the Mongols. Thus in 1263-3, by the decree of Hulagu, Ebesh Hatun was

brought to the throne of Fars without encountering any more opposition

than a male heir would have done; her name was read in the Friday prayer

and money was also minted inscribed with her name and ranks. So she was

an official ruler according to Islamic Law.

She married Hulagu’s son Mengü Timur as second wife. Because of the

discontent in Fars caused by the high taxes, Ebesh after her marriage

moved to Ordu, considered as her husband’s home. Here she spent some

years before returning to Shiraz where she was warmly welcomed by her

people.

Her supporters assassinated her rival, the regent of Fars Seyyid

Imadüddin Ebn Ya’la on 21st shevval 683. But his son took a violent

revenge. Only Ebesh Hatun, by virtue of her position as Hulagu Khan’s

daughter-in-law, which was vouched for by her mother-in-law Oljay Hatun,

was able to escape trial and punishment.

Ebesh was the last of her line, while also being the daughter-in-law

of Hulagu Khan. With her death, the state of Fars would be annexed

directly to the Ilhan Empire. It was therefore necessary to ensure that

no new dynasty should appear at this juncture to form a fresh obstacle

to the Empire.

Ebesh died in 1286-87 after having ruled for 22-23 years. They buried

Ebesh Hatun at Cherendap, which was the summer camping ground for

Tabriz, with gold, silver and wine, according to Mongol custom; but they

did not leave her there for long and she was later taken to her own

city of Shiraz where she was buried in the Adûdiyye Medrese her mother

Türkân Hatun had had built.

It is clear that the people of Fars were extremely contented during

the reign of Ebesh Hatun. However, a train of political events, added to

the refusal of the Mongol Khans to leave small states like this in

peace, condemned Fars to be annexed by the Ilhans and to the misfortune

of being administered as a province by the Mongol Baskaks.

So the successful reign of this female ruler Ebesh Hatun was destined

to fall into oblivion, and the same happened to the idea of

independence of Salgur.