Is comparing France and USA irrelevant? About the mobilizations for George Floyd and Adama Traoré

|

| Audrey Célestine 09/06/2020 |

Tens of thousands of demonstrators marched against racism and police violence in the United States and France on Saturday, June 6.

Tradotto da Fausto Giudice

The parallel between the two situations still arouses scepticism in France, where commentators readily denounce the importation of inappropriate categories, unsuitable analytical grids, or even USAmerican communalism. However, sociological studies have shown in recent years how race and ethnicity are viewed, shaped and worked on by the State and the administration in France, in opposition to the “colour-blind” narrative.

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, an African-USAmerican man, dies while Derek Chauvin, a white policeman from the city of Minneapolis, presses his knee against his neck. George Floyd is handcuffed, repeatedly says he cannot breathe. None of the police officers present react. Floyd dies after a few minutes. The scene is filmed by a 17-year-old bystander. The video of this man’s death travels across the country and around the world, prompting large demonstrations demanding justice for George Floyd and an end to police violence. The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter remains a major trend on Twitter.

In France, 24-hour news channels devote large segments to these protests and the “riots” they spark. It is in this context that the Truth for Adama Committee calls for a rally to demand justice for a young man who died during a gendarmes’ intervention in the town of Beaumont-sur-Oise in the Paris region. The young man died in July 2016, the versions of the gendarmes and the family diverge, the medical expertise requested by justice and which clear the gendarmes and point to a prior illness of the young man are contradicted by independent expertise requested by the family. Following the publication of the latest expert opinion, a rally is organized in front of the Judicial Court at Porte de Clichy.

The appeal is launched by Assa Traoré, sister of the victim and charismatic figure of a movement that has been growing steadily for 4 years, via social networks but also through participation in numerous demonstrations denouncing social and economic inequalities in France. On June 2, a few hours before the rally, the police prefect, Didier Lallement, banned the rally. The family maintains it and is followed by several thousand people, often very young, who converge on the court, from the centre of Paris and its suburbs. As in the United States, the signs bearing the words “Black Lives Matter” are very numerous. As in the United States, there are calls for justice, an end to police violence and racism in the police and in society. As in the United States, most of the demonstration is peaceful.

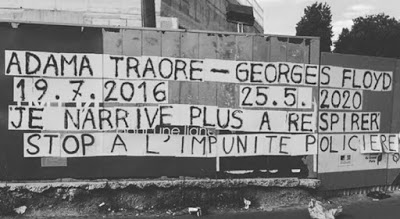

From this mobilization, which is surprising by the number of people it brings together, more than 20,000, television and social network reports and debates focus more and more on the differences between France and the United States and the abusive importation of a very “American” movement. “”Comparing is irrelevant” can be heard to draw a clear line between two situations that would be quite different even though the Traoré family insists on the convergence of the two situations: Adama Traoré and George Floyd are two black men killed by the police because of lethal techniques that caused their asphyxiation. Accusations of importing inappropriate categories, unsuitable analytical grids or even American communalism or identity politics in France are commonplace for anyone interested in racism, anti-racism and the mobilization of minorities in France.

The Black Lives Matter movement is part of a long history of racial injustice understood as a structural and long-term phenomenon.

However, we can recall – as several texts published in recent days and research done in recent years have done – a long history of racism and racialization processes in France. For several years now, social science researchers have been showing the symbolic and practical traces left by slavery and its abolition, the links and exchanges between colonial and metropolitan forms of racialization, the ancient history of the production of race in France and that of “Blacks” and “Whites” in the French context, etc. Sociological works also show how race and ethnicity are viewed, shaped and worked on by the State and the administration in France, in opposition to a “color blind” discourse supported by what Silyane Larcher calls “an abstract universalism that operates as a social norm”.

The gathering for Adama Traoré, and the reactions of support and condemnation it provokes, is nevertheless a very good way of understanding the dynamics and logic of 21st century France in terms of racism and anti-racism and what they owe to USAmerican issues and debates through the forms of appropriation to which they give rise. Above all, it allows us not to limit ourselves to a statement of “USAmerican influence” but to understand why young French activists identify the case of Adama Traoré as equivalent to the many cases of police violence against Blacks in the United States. Why do events that seem so rooted in a long history of racism and the relationship between the police and black people in the United States seem to resonate so strongly with a part of the French population?

The Black Lives Matter movement was formed in the United States in 2013 following the acquittal of George Zimmerman accused of killing young Trayvon Martin in July 2012. The development of the movement gave rise to numerous writings and works on police violence in general and against black people in particular. Social networks have become a space for denouncing this violence, a sounding board for little publicised cases to press for investigations, a space for disseminating work, writings, statistics, words of comfort to those who would be particularly affected, slogans, the first of which #blacklivesmatter or #sayhername to highlight the difficulty of bringing out the problem of police violence against black women.

The movement has also made it possible to disseminate analyses around the black body as the primary target of oppression, as Nicolas Martin-Breteau points out in his book Corps Politiques (2020, EHESS Editions). Probably the best known is that of the journalist and writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, who wrote this long letter to his son on what it means to live in a black body in the United States. The Black Lives Matter movement is part of a long history of racial injustice understood as a structural and long-term phenomenon. The denunciation of police violence against black people is also part of a long timeline that can be traced back to the history of slavery and population control during Segregation.

In its structure, largely horizontal, and its deployment, with the irruption of numerous figures who put forward an intersectional approach, Black Lives Matter is also a very contemporary movement that breaks both with the logic of the politics of respectability that have long marked black movements in the United States and with the emphasis on male and heterosexual leadership. Three women created this movement. Two of them define themselves as “queer”. These elements are important because they reveal a complexified understanding of what “black life” in the United States is all about. In fact, despite the centrality of a “line of color” distinguishing between whites and blacks in the United States, the political, intellectual, artistic productions, as well as the daily lives of ordinary black people in the United States are marked by circulations from the Caribbean yesterday, from Africa since the 1960s.

As early as the 1930s, the work of the author, anthropologist and documentary filmmaker Zora Neale Hurston gave real depth to the realities and experiences of those who were referred to as “Black”. The novels of Paule Marshall or Jamaica Kincaid infuse this broader understanding of the “black experience” by depicting the comings and goings of Caribbean populations in the United States. In the Black Lives Matter movement, it is this broader, more comprehensive understanding that activists are attempting not only to describe but to politicize as they denounce a phenomenon rooted in USAmerican history. And it is in this attempt to hold together a re-humanization of the “Blacks” and a denunciation of a system that turns them into threatening presences and normalizes violence against them that a form of resonance here in France can be found.

The intimate (a)knowledge of a particular form of dehumanization, although better documented in the case of the United States, is not radically different from what is done and played out in France.

In the case of France, official studies and reports suggest that one of the points of resonance with the United States is the reaction of law enforcement to these bodies of young black men in particular. It is the systematic control, the familiarization, the racial profiling, the insult and the suspicion for whom, in France, “lives with” a black body and, most often, a male body (the author of these lines has been controlled “only” twice in France – which is nevertheless more than all her comrades, yesterday, students at Sciences-Po, today university colleagues – but much less than all the black men in her family).

What is at stake here is the intimate (a)knowledge of a particular form of dehumanization which, although more documented in the case of the United States, is not radically different from what is being done and played out in France. This resonance is obviously not sufficient to establish “that in France it is the same as in the United States,” of course. It does, however, open the way to a comparison that constitutes both an invitation to distance and an epistemological rupture, allowing us to question what is obvious or natural, to reconsider categories mobilized here and there. In the field of racism and anti-racism, as in the study of minorities, it allows us to question French and USAmerican models that would supposedly be radically different and opposed.

For researchers working on France, the works developed in the United States has often provided a conceptual apparatus for grasping issues that are less present in the French academic context. But the comparison has another virtue: when applied to collective mobilizations, it provides a better understanding of how the national context shapes the issues on which to mobilize and how to do so. The denial of the French logic of the production of race and of “Blacks” through, in particular, police action and violence against “Blacks”, makes it necessary for many to look elsewhere to find the words of anger.

The history of slavery, post-slavery societies, the French colonial world, decolonization and departmentalization of former colonies, post-colonial migrations, anti-racist mobilizations and forms of the presence of black populations, their artistic, literary, political and intellectual production in France yesterday and today have shown the importance of the circulation of people, ideas and ways of fighting oppression between France, the Caribbean and North America.

The appropriation of “American” slogans by young people mobilized on the issue of police violence today is part of a longer history of these movements between France and the Americas, which weakens the idea that the two situations are “incomparable”. Above all, however, to be audible and valid, these criticisms of a too quick comparison must, at the same time, invite us to study, analyze and take note of the historical and social configurations that bring race, racism and anti-racism into the French context and not sink a little further into denial, which is a very French feature.