Notes on a night of terror in Palestine

|

| Caco Schmitt 27/02/2020 |

It is two a.m. during the night from Sunday to Monday in Ramallah, provisional capital of Palestine. I am awakened by the sounds of fighting and quarrelling. Strange. For 12 nights I slept in this elegant neighbourhood hotel and never heard noises at night. There are few guests, and no one has ever arrived drunk, speaking loudly. I sit on the bed, facing the door and with my back to the window.

Tradotto da John Catalinotto

Editato da Fausto Giudice

The noises grow louder, with sounds of objects broken, screams. I think: It’s them! A loud bang confirms it. The door is broken down and four Israeli army soldiers enter the room screaming and with machine guns and rifles pointed at me. I raise my hands, close my eyes and remain still for endless seconds. They scream words in a language unintelligible to me, with the tip of their rifle touching my chest. I think: They will kill me! But I don’t hear any shooting.

I open my eyes and start talking out loud: Brazil (with an American accent), Brazil! Brazil! The shouting stops, but the guns are still pointed. I realize what’s going down. In front of me are two soldiers in masks, armed to the teeth. At the foot of the bed, another soldier; behind, the fourth masked soldier with his rifle pokes my back. With the door open I can see in the fourth floor corridor a dozen soldiers, dogs, sledgehammers breaking doors, men being torn from their rooms.

Brazil, Brazil, Brazil… Here comes a fifth soldier, I notice that his mask is different, he has a scary skull sticker, he holds a dog, he also wears a gas mask stickered with a human skull. He comes out, the guns keep pointing, sledgehammers breaking everything, until a sixth soldier appears, a short one, and asks me in a butchered Portuguese: “What are you doing here?” I answer: “I’m a Brazilian journalist, we’re filming Palestine.” He faces me, orders me to put on some clothes — I was just in my underwear — which I do quickly and sit back on the bed.

II

The tip of the machine gun pokes my back hard several times, I don’t turn around. The short guy without a mask signals me to get up, which I do without breathing so as not to look like I’m reacting. Two of them start pushing me with the tip of their rifles. The four apartments in my wing of the hotel, two on each side of the corridor, are being turned inside out by soldiers, walls and upholstery broken, shouts, masks and dogs. I get to the elevator, they poke me in the back and send me down the stairs, which I walk down accompanied by two masked soldiers.

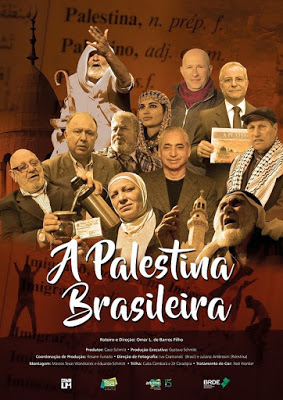

While I walk down the stairs, I think of everything I saw in the 12 days we were in occupied Palestine to shoot scenes for the documentary “A Palestina Brasilaira (The Brazilian Palestine),” by director and scriptwriter Omar Luiz de Barros Filho, produced by CenaUm Produções. To enter Israel, on October 26, 2016, was extremely difficult, starting with our landing at Ben Gurion airport, which is between Tel Aviv (20km) and Ramallah (50km).

Interrogations at the customs counter, suspicion, a tense atmosphere. A member of our team tried to take a selfie and an Israeli soldier came over to interrogate them. From the airport to Ramallah, the first sign of the military occupation: two checkpoints, but we passed freely; the search in these places is only done for those coming from Palestine. In the vicinity of Ramallah, the first big shock: walls built by Israel and a mega checkpoint controlling entries and exits. The Palestinian who needs to go to Tel Aviv, and wants to use this road, must wait hours in lines at the checkpoints and many are forced to return. To drive by car on this and other roads controlled by the Israeli army is only for those with yellow plates on their vehicles.

Our team, even though we used a rented car with yellow license plate, was blocked when we tried to leave Ramallah to get to Ben Gurion airport when returning to Brazil. The soldier claimed there was a lot of luggage and we should go through another checkpoint.

III

It was harder to get out of Israel than it was to get in. We took another road, a long, unnecessary detour to one of the access checkpoints to Jerusalem. A new checkpoint, questions and then we headed towards the airport. At the entrance to Ben Gurion Airport was another big checkpoint, with a search, explanations, again presenting passports, tickets, etc. Whew! We arrived at the boarding lobby. We are free!

A deception. Near the check-in counters, the worst of all, were soldiers and agents of Mossad, the secret service created in 1949, one year after the establishment of the state of Israel. Heavier, more aggressive interrogations, explanations, labels separating our bags for special checking. Of course, we had already been identified at our entry into Israel and in the filming of each conflict we witnessed, and especially at the time of the hotel invasion, two days before our return.

But the departure from Israel did not end at this unprecedented checkpoint inside an airport, ten meters from the check-in counter. After the tickets were issued, we were taken to a basement, where special machines checked our hand luggage. Soldiers and an old Mossad agent sat and watched. This gentleman was intrigued by our electric lighting reflector, which when it was not being operated turned into a round circle the size of a family pizza. New explanations, it could be plastic explosive. We decided to leave our work tool with them …

We moved on to the boarding area. A new delay. Because he was carrying a camera in his hand, one of the photo directors of the team was forced into a separate line, searched, forced to stay in a kind of X-ray, a mysterious and dangerous cabin. After leaving the cabin, he wanted to continue his journey, but was forced to remain in “quarantine” for 20 minutes so as not to expose the airport staff to radiation. We almost missed the flight, but the plane waited on the runway, an airport employee took us running to the gate at the boarding bridge. But the camera was held up on suspicion of containing explosives and has not been returned to date. A valuable loss. Until never again, as long as the illegal occupation of Palestine and apartheid continue.

IV

At each stair step to the hotel reception on the ground floor, escorted by two armed and masked soldiers, without knowing where they were taking me, I thought about each movement we made on Palestinian territory, to do our work visiting families of Palestinians who emigrated to Brazil and Brazilians who came here in search of their roots. We traveled the territory from north to south. We went to Nablus, in the north; Jericho, on the border with Jordan and close to the Dead Sea; in the center, Jerusalem and Bethlehem; and, to the south, Al Khalil, also known as Hebron. For a few days we faced intensely what the Palestinian people experience all the time.

Most of the Palestinians stay in their villages, small towns, close to each other; from time to time they go to Ramallah, or to the larger cities. It is always complicated to travel through a territory occupied by the military. Checkpoints, unpredictable reactions of arrogant and nervous Israeli soldiers, delays, assaults, shootings, gas bombs and unjustified arrests are the norm. Even on Fridays, when thousands are going to Jerusalem, to pray at the sacred Al Aqsa mosque, controlled by soldiers at the gates to the old city, at the access to the mosque, each and every movement is under the watch of helicopters.

On the second day of filming, we left early for Kafr Ni’ma, land of protagonists of the documentary. Next door is the Palestinian village of Bil’in. Less than one kilometer from Bil’in, there is an enormous Jewish settlement, the Kiriat-Sefer, with dozens of tall buildings, protected by a gigantic wall. A body foreign to the landscape of low mountains, olive trees and houses at most two stories high. In the half of the territory that belongs to the Palestinians by decision of the famous and not respected UN Partition Plan for Palestine in 1947, Israel invaded and built several “settlements” like this one that are actually illegal cities in Palestinian lands. After recording walls and checkpoints for the film, this was the first time Israeli forces launched gas bombs against the demonstrators and the film crew.

V

Friday in Palestine is the day to protest the military occupation. We accompanied a protest, with the presence of activists from several countries, in front of the gate of the great wall. The army launched tear gas bombs with a deadly effect. Everyone ran. Then, the soldiers remained in a shooting position until the demonstrators returned to the starting point of the march, some 400 meters from the wall.

I remember the confrontation that took place when we left Ramallah for Jerusalem, at the Kalandia checkpoint, an old refugee camp that became a working-class neighborhood. We filmed the lines of Arabs passing by on foot to enter the gate of the checkpoint, and then return to the bus ahead. And we filmed the entrance and exit of cars. As we approached the gates, two soldiers pointed rifles at us. Later, we started filming the pedestrians and a megaphone voice screamed from the top of a control tower: “What’s happening there?” The fourth time, the sentence was accompanied by threats that we did not understand, but which − we played it safe − forced our withdrawal.

Filming in occupied Palestinian territory is dangerous. If you raise the camera and point the soldiers can shoot and claim that your camera could be a firearm. Everything has to be done very carefully. And this within the Palestinian territory recognized by the UN, and that on the maps (not all) appears as West Bank or Israel.

VI

One time we took Highway 60, with two lanes and well paved, towards Jerusalem and Bethlehem. For a distance of 10 km only Arab cars with white plates circulated. On this road, we passed a very different kind of checkpoint. With an observation tower, an Israeli flag and soldiers, it does not regularly stop the cars, but when they decide it is necessary, they quickly set up a barrier to prevent vehicles from circulating.

Drones and satellites are used to watch everything that moves. Throughout Palestinian territory there are these kinds of installations ready to block any movement. In any corner you can see dirigible balloons with cameras that watch everything, helicopters on patrol, observation towers. All this is relatively far from the Gaza Strip.

In the comings and goings of the cities and villages we visited, including the capital Ramallah, we always passed through checkpoints, with armed soldiers on watch (scared, they feel afraid). In the vicinity of villages and towns known to resist the occupation, the Israeli army’s observation and control towers control all movement on the highways. When we went to film the mountains in some of these areas, we were observed by soldiers. At each step a soldier. Sometimes they block the secondary access to the villages with concrete blocks, to prevent vehicles from passing through and concentrate the observation on the main access to the village. We felt this pressure during the two weeks we were in Palestine; it is constant and growing. The Palestinian people have felt this same pressure for over 80 years.

VII

When I reached the hotel lobby, brought there from my room by soldiers, and saw a group of Palestinian hotel staff, all sitting on chairs and armchairs that formed a horseshoe, I was relieved. It meant I would first go through a screening, not taken immediately to some uncertain place. Among the people arrested in the hall were the director of the film, Omar Luiz de Barros Filho, and the director of photography Ivo Czamanski. They were seated, quiet, looking worried like everyone else in the room. Guarding the group were some 15 Israeli soldiers, while many others ran up and down stairs, some carrying sledgehammers, others with electric saws and all with weapons.

Our passports were taken and each of us was photographed, filmed and interrogated. As I had already talked to the short guy in the room, they only had two or three questions for me. I could see that there were soldiers from the army, plainclothes policemen and Mossad agents, including the one in charge of the operation, a gray-haired man with a rat face. Inside the hotel, I believe, 40 men took part in this operation, whose objective no one could figure out. Were they trying to intimidate us, to pick up the filmed material? − after all, we had several contacts with the military and they followed every step of our team near checkpoints, walls, in the protests. In that case they were stymied, because the day before a Palestinian-Brazilian friend brought to Brazil all our main digital files, with everything we had recorded before with our two cameras.

VIII

I started to mentally relive our two trips to Jerusalem. On Friday, we filmed the movement around the Al Aqsa Mosque during the holy day in the holy city for Muslims, Christians and Jews. At Al Aqsa, there were more than 300,000 Muslims, plus wide-eyed Israeli soldiers, helicopters, guarded gates, all there after passing through and being identified and searched at the checkpoints surrounding the city. On Sunday, November 6, 2016, a few hours before the invasion at the hotel, on our second visit to Jerusalem, we had had another serious incident with the Israeli army. After filming the city, we intended to return to the Al Aqsa mosque, where Muslim religious figures expected us. On the road indicated by the producer, a Palestinian-Brazilian, we were all barred and sent along another access route. We went until we bumped into a checkpoint inside one of the old city corridors. Because our producer and interpreter was of Palestinian origin, the police sent him back, saying that he was not going through there. Although we identified ourselves as journalists, we were detained for over an hour. We tried to give up entering and told them we just wanted to return to where we had been, but the police still stopped us. In other words, they refused to let us go until they found out what we were doing there. Director Omar Luiz de Barros Filho was then taken to a police barracks, where he was subjected to further questioning.

That’s how he was forced to sign a commitment written in Hebrew that prohibited interviews or using lights and any use of sound recorders. Only that way were we released from the blockade, and we entered the square where the Wailing Wall is. From there we kept going, through the streets, towards the mosque. There, the Israeli police once again forbade us to go beyond their control. We remain in debt to our spectators, as we could film nothing from inside Al Aqsa, taking only general shots taken from a tourist terminal.

IX

While I considered all the possibilities of how this military operation might end, I remained calm because all the material filmed up to that moment was safe, kept in the house of friends. And I was even calmer when I saw the fourth member of the team coming down the stairs, the director of photography Juliano Ambrosini, escorted by two armed soldiers, and joining the group of detainees in the lobby.

My concern grew when I imagined what our fate would be. One of those in charge of the operation said, in English, that everything was almost over, the operation would end soon. But the back-and-forth of soldiers continued, much of it determined by bombs that exploded outside the hotel. Then we learned that the Israeli troops’ movement caught the attention of the inhabitants of Ramallah, and many Palestinians came to the vicinity of the hotel to protest. The army dropped bombs to intimidate and drive the masses away.

Shortly before, on the streets of the city, the Palestinian resistance threw homemade bombs at the Israeli armored vehicles that still surrounded the hotel where we were staying. After all, an army from another country was carrying out an illegal military operation, a night invasion, almost in the center of the Palestinian capital. Minutes later, the same officer entered the lobby again and said the great sentence of the night: “No panic, no panic.” How could we not feel panicky? If the conflict got worse with the Palestinians in the street: shots would be fired. If someone in the room moved and the gesture was interpreted as a response: shots would be fired. Just the thought of stray bullets and uncontrolled actions of soldiers, a common occurrence in Palestine, surrounded the room with panic. Until later, finally, the big boss said they were retreating… A feeling of relief invaded the room, soon aborted with the entrance to the Mossad’s rat-faced gray man. “Video, video.” New butterflies in the belly. They wanted our footage, I thought, but luckily, it was the footage from the hotel security cameras. They grabbed the computers and started leaving. For a few minutes, everyone sat there, nervous. Until the first one stood up and started protesting. I went up to the room and started collecting the pieces of clothing scattered across the bed and the floor. The safe was open, but nothing was taken. In our director’s room up to the ceiling line an axe had smashed the wall. I looked at the cell phone, over five hours since it started, day almost dawning…

Four hours after the night of terror, we headed for Al Khalil (Hebron), a city inhabited uninterruptedly for over five thousand years. Our last location to film in Palestine. On the way, the realization that there were more Israeli army armored vehicles in the streets and on the roads. On the way, we crossed several roads and saw many vehicles stopped in observation position. There was a feeling that something serious was about to happen in the territory and, because of this, increased vigilance. When we arrived in Al Khalil, we had to make the return under observation of two military vehicles, attentive to any maneuver.

Hebron is a special case. According to the Palestinian Administration’s public relations on the spot, there are two thousand Israeli soldiers watching the region. They have created areas where only Jews enter or where only Palestinians circulate. All because of the Ibrahimi mosque, which houses the tomb of the patriarchs of the three religions of Muslims, Jews and Christians. In order to film, we had to pass, at great cost and thanks to pressure from the Historical City administrator, through an obscure checkpoint buried in the corridors of the public market, which gives access to the main door of the mosque. Anyone who wishes to pray at the mosque is forced to pass through it. All around, soldiers police the area.

After the mosque, we went to Fawar refugee camp, one of the oldest in Palestine, where we recorded scenes and testimonies while two helicopters flew over the area. In this last location of the filming, we saw the summary of the whole situation in Palestine: people who were forced to leave their homes, who have lived for decades surrounded, isolated and guarded within their own land. I thought, after the night of anguish in our hotel, that it is the Palestinians who still resist in refugee camps and live in surrounded cities that live, to this day, a long night of terror!