Palestinian bedtime stories: The wicked Israeli witch

|

| Tamam Mohsen 01/10/2019 |

I recall clearly from my childhood, how my mother’s face would change in the evening.

She would remove her stern and austere face and become tender and dreamy. She would tell my siblings and I thrilling stories like “Jabina” or “Half and Half” and a lot of tales where the dreaded ogress “Al Ghoula” was the lead character and how our hearts would fall when she would repeat that thrilling phrase “Go oh day and come oh day” which would whet our longing for the story.

Bedtime stories told by mothers and grandmothers have always served as a child’s first glimpse of the cultural and intellectual heritage of a people and Palestine is no exception. This was of course before this evening ritual was threatened by new modern means of entertainment like smartphone and tablets which have weakened the relationships with mothers in exchange for an increased attachment to screens and from oral storytelling that is inspired by the environment and the reality of a child to cartoons and videos that reflect another reality and more often than not another culture.

Magic, safety and affection

Nidaa Ouina, a journalist from Ramallah has preserved this daily ritual with her daughter Raya (6 years old) and tries to maintain a strict bedtime at eight-thirty but her curious questions can often delay this by as much as an hour.

Ouina says “When we were little my Grandfather and Grandmother would tell us stories, My Grandpa liked stories of intelligence and cunning like the ironmongers and Al Ghoula while my Grandmother liked stories such as Jabina or the old lady and the milkmaids”

“We grow up hearing these stories, our generation is very different from this generation mostly due to the media and since a lot of mothers find it easier to leave children in front of a tv or with a smartphone”

For that reason, Ouina decided to devote an hour before bed to sing songs or tell her daughter Raya a story. “Story-time is time for Raya and me to bond more than anything else, it’s a relaxing time when we cuddle and I tell her a story till she drifts into sleep”.

Ouina chooses the story carefully, in order to pass down social and patriotic values to her child “by tweaking the events of the story and their context” like making the evil witch Israeli for example explaining that “Raya is too young to understand the Arab-Israeli conflict and abstract ideas like patriotism or morals so I try to pass down these values through stories”.

Palestinian story telling necessarily involves patriotic and historic moments, for, after 70 years in exile and as refugees, the dream of a home remains vivid for those telling the stories, hoping their children will want to return to their homeland one day

She adds, “I don’t like stories like Cinderella or patriarchal stories that revolve around princes saving girls from their troubles and the only way to save herself is by getting married or that she needs to be beautiful and well-groomed to find love, these are poisonous ideas which is why I tell her stories from the past that praise strong, intelligent, decent people or sometimes comical, funny stories”.

Raya does not listen quietly to stories, she might object to some of the events or demand an amendment to the story like for example turning “Snow White and the seven dwarves” into “Snow White and the ten girls” or place conditions before the story is told.

“Imagining colours and scents”

Nour Al Sawirki, a feminist activist from Gaza, says that telling a bedtime story contributes to determining the trajectory of the relationship of a child to its mother and helps develop children’s imagination, it makes them imagine how the hero of the story looks like as well as colours and scents.

Al Sawirki tells Raseef22, “Bedtime stories give children a safe space to escape from the security situation in the country, an incident with the family, a frightening youtube video, the story provides them with a haven to allay their fears”.

Al Sawirki, a mother to two tries to instil constructive ideas in her children through telling stories saying, “I make sure that there is a message in the story and sometimes I use expressions with certain connotations so I can fit it into their intellectual makeup, they don’t have to fully understand at that moment but it expands their thinking and leads them to compare incidents with the story”.

To find a story with Sawirki’s criteria and objectives is no easy task and often she has to invent her own stories as she believes that folk-tales both local and international are full of stereotypes and trite ideas especially when it comes to how they portray women and their relationships with men “the loyal heroes” as Sawirki calls them.

On the other hand, many busy mothers and especially working mothers are often forced to leave their children in front of a television or with a smartphone until they are sleep instead of sitting with them and telling them a bed-time story.

Mona Hijazi (26) a Palestinian living in Turkey described her experience with her first child to Raseef22. Due to her former job as a journalist, she was forced to leave her child with a smartphone for hours and this she believes delayed his ability to speak.

She believes that technology is not entirely bad because it helped her child to pay greater attention to the images, colours and sounds in videos and to follow their movements and imitate them but affected his ability to speak “he converses in an incomprehensible language that is not Arabic”

Now that she has another child Hijazi combines the use of technology with oral storytelling as she sees that denying a child access to technology completely is detrimental, explaining that “ there are educational animations that teach children in a way that is beautiful and really captivates them and there are stories told through voice or with animations which is why now I tell them stories while changing my voice for different characters at the same time we watch videos on youtube that are very useful”.

Children wondering about a lost homeland

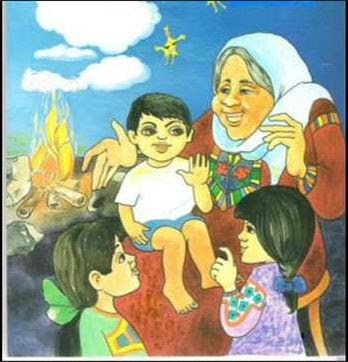

Nabil El Arini, a writer of children’s literature and Palestinian folk tales, created a story collection based on stories told by Grandmothers called “Sitti’s (Grandma’s) stories”. He said that the book for children and young adults is a “rich meal” of history, geography, customs, traditions, folklore and heritage that make up national identity.

Al Arini was inspired to create this book, which is currently being printed, by the stories that his grandmothers told his father and mother with their narratives about Palestinian history.

Al Arini told Raseef22 that the primary motivation for writing the series “Grandma’s stories” are his daughters Bissane and Janine who were born in the diaspora to refugee parents who themselves were the children of immigrants and who have relatives scattered all over the world. “Their confusion and need to belong to a certain land, a sky and a body of water made them wonder about a homeland that had been lost to them for seven decades and as a father, I had to answer my children’s many questions and instil the answers within them”

Al Arini added, “I thought that “Grandma’s stories” would help me answer the huge number of questions as the book contains many stories that mothers and grandmothers would tell their children at bedtime.”