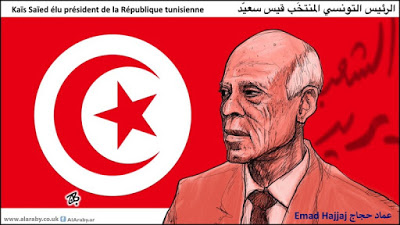

“Allow us to disagree with you”: why Kais Sayed was elected Homage to Tunisia

|

| Abdelbari Atwan 20/10/2019 |

The country continues to serve as an inspiration for the rest of the Arab world.

Tunisia keeps on springing surprises, pleasant ones included. Its latest pleasant surprise was the landslide victory of retired constitutional law professor Kais Saied in the presidential election run-off. He won twice as many votes as his predecessor the late Baji Caid Essebsi, and more than the total number cast by voters who took part in the country’s parliamentary polls.

Essebsi is reckoned to have won the presidency largely on the strength of the women’s vote – 1.2 million out of 1.7 female voters backed him. The votes of the supporters of political Islam earned the Ennahda party 52 of parliament’s 217 seats, down from 70 at the last legislative elections. But the new president was propelled to office primarily by the youth vote: 90% of 25-29 year-olds cast their ballots for him, in a country where 60% of the population is under 26 years of age.

His secret weapons were qualities that are rarely found among members of the Tunisian elite or Arab political leaders in general: modest; erudite; down-to-earth; unconcerned with media publicity or money or power; devoted to the Arabic language unlike the francophone elite; and committed to Arab causes, especially Palestine. He declared during the televised pre-election debate with his rival Nabil Karaoui that normalisation with Israel, as an entity which had dispossessed an entire people, was tantamount to high treason, at a time when other Arab rulers and their proxies are desperate to dump the Palestinian cause.

Saied’s opponents, including much of the elite, say privately that they are worried that he will not prove capable of running the country. He has no political party to support him, no previous public profile, no political machine, no experience of government, and no prior association with the ‘deep state’. How, therefore, can he push through the political, economic and social reforms he espouses, manage the executive authority, or select appropriate ministers of defence and foreign affairs, as is his prerogative as president?

Some of these critics go further, claiming that the election of Saied heralds a resurgence of the Muslim Brotherhood – on the grounds that Ennahda backed him after he beat its candidate Abdelfattah Mourou in the first round – and the country’s transformation into a ‘Tunistan’. These fears, whether sincere or not, are groundless. Ennahda obtained less than 20% of the vote and was a major loser in both the presidential and parliamentary elections. It is no longer the country’s political ‘kingmaker’ as it used to be.

Tunisians were looking for many things when they went to the polls, after feeling that their 2011 revolution was been hijacked by a corrupt ruling elite. They wanted to reaffirm an inclusive national identity; to uproot corruption from top to bottom of the political system; to consolidate the rule of law and disengage completely from the former regime, and to uphold justice in the Arab and Islamic causes and especially in Palestine. Saved was elected because he embodied and upheld those values and demands.

Tunisia may be a small country in size and population compared to its neighbours and other Arab countries. But its influence far surpasses its borders. It pioneered the mass popular protests demanding change that proceeded to sweep much of the rest of the Arab world. And as its people affirm their commitment to holding on to their hard-won freedoms and taking their society forward, it continues to serve as an inspiration to all.