The last eyewitnesses: a new film on the Nakba

|

| Stephen Shenfield – February 19, 2019 |

Today marks the release of a new film on the Nakba, entitled “1948:Creation & Catastrophe.”

Stephen Shenfield interviews co-directors and executive producers professor Ahlam Muhtaseb, head of the Center for Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies at California State University at San Bernardino, and Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker Andy Trimlett.

Stephen Shenfield: Ahlam, please tell us how the Nakba has affected you and your family.

Ahlam Muhtaseb: Although I am of Palestinian origin, I am not a refugee. I grew up on the West Bank, in the city of al-Khalil (Hebron), under Israeli military occupation – one of the harshest colonial regimes in the world and part of the ongoing Nakba. I remember a childhood of long curfews, closures, and night raids to arrest my father and two brothers. My father was a political prisoner. He was arrested many times and suffered electric shocks and other brutal forms of torture. I also grew up witnessing the wonderful resistance to the colonization of Palestine, especially during the first Intifada.

What led you to embark on this project?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: It started with my field research in the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon and Syria. I was studying the refugees’ narratives of exile as they evolved from one generation to the next and how those narratives shaped their memories and identity. I wanted to create a short video of life in the refugee camps that could be used as a classroom resource. In 2006, after getting a few grants and buying equipment, I started filming in Syria and then in Lebanon, but my work was interrupted by Israel’s invasion of Lebanon. In 2007 I met Andy. I had intended to return to the region and continue my project in 2008, but Andy persuaded me to switch to a somewhat different film project – a historical narrative of 1948.

Andy, why did you feel the need for a new film on the Nakba?

Andy Trimlett: I spent years studying the Middle East, ending up with a master’s degree in Middle East Studies from the University of Washington. And yet I never truly understood the Israeli-Palestinian conflict until I began digging deeper into the events of 1948. Only then did it all suddenly click and I grasped the forces that still drive the violence today.

Do you mean to say that in all your years studying the Middle East at university you were never taught about the Nakba? You learned of it only later, when you began “digging deeper” on your own?

Andy Trimlett: No, I definitely learned about the Nakba. I was not denied any part of the story. I knew the facts, the figures, the people and places. But, to be frank, I didn’t get it. I couldn’t wrap my head around why this conflict continues to this day. I viewed 1948 as one of many wars and flare-ups in a long chain of violence between Israelis and Palestinians. Then after graduating I started researching the events of 1948 in greater depth. And that is when it all clicked.

Once I understood 1948, everything that is happening today made sense – the settlers, the home demolitions, the checkpoints, the wall, the violence. This is basically a conflict over land and who lives on that land. Throughout the entire history of the conflict, one side has been pushing the other side off the land through a variety of means. In recent years this process has taken place by creating unlivable conditions for Palestinians and by confiscating Palestinian land through the construction of a wall that runs deep into the West Bank. In 1948 it was done by means of active expulsions.

So the key to making sense of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is to look at today through the lens of 1948. If I had gone through an entire graduate program in Middle East Studies and still couldn’t make sense of the conflict, then what chance – I asked myself – did an average American watching MSNBC, CNN, or Fox News have of understanding it? I decided that the critical first step on the path to peace was to bring the history of 1948 to the American public. Someone had to make a documentary about 1948.

But yours is not the first film about the Nakba. A documentary on the subject entitled “Al Nakba” and directed by Benny Brunner and Alexandra Jansse was released in 1997. I watched it on Vimeo. Their film and yours serve a broadly similar purpose. Why did you think that a new film was needed?

Andy Trimlett: “Al Nakba” was definitely a great documentary. I believe it was the first to take on this subject. I remember watching it in class just a few years after it came out. It was the first time I was ever really exposed to this story. I had so many questions afterward.

1948 certainly takes on the same subject. We even interviewed a few of the same people. But there is so much more available now than there was in 1997. Brunner and Jansse made their documentary shortly after the publication of Benny Morris’ groundbreaking work “Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem.” So much has come out since that time – several more books and articles by Morris as well as publications by Walid Khalidi, Yoav Gelber, Nur Masalha, Salman Abu Sitta, Rosemarie Esber, Ilan Pappe, Avi Shlaim, Rashid Khalidi, Charles Smith and Yoram Kaniuk, among others.

Ahlam Muhtaseb: I agree that it was a great film. However, our narrative of the events is more detailed and systematic. We also made greater use of archival documents, including some that were not declassified until after the Brunner film was released. And we interviewed all the well-known historians who have written about the Nakba, while they interviewed only Benny Morris (though he was different then).

Andy Trimlett: We retrieved copies of original orders from Israeli archives calling on military units to, for example, “Liquidate Arab settlements within this area;” “Expel the Arab refugees from those villages and prevent them from returning again by destroying the villages;” and “Occupy the villages, cleanse their inhabitants (women and children must be deported).” Seeing the original Hebrew and then the English translation of these orders is quite powerful in convincing a skeptical audience of the authenticity of the story.

Were there Israeli archival documents to which you were unable to gain access?

Andy Trimlett: We had access to a pretty extensive collection of both documents and photographs at Israeli archives. We were able to gather a massive collection of 2,000 archival images and film clips from 1948. All of the military orders featured in the documentary came from Israeli archives. That said, I do know that there are documents and photographs that are still inaccessible to the public.

I should add that the archives of documents from 1948 in Arab countries are all still sealed. For a complete understanding of what happened in 1948 it is necessary that all archives be opened.

Ahlam Muhtaseb: After declassifying many documents from 1948, the Israeli authorities went back and reclassified many of those documents after the ‘new historians’ used them in their scholarly work. In 2010 Netanyahu extended the embargo on classified documents from 50 to 70 years. Now it has been extended to 90 years!

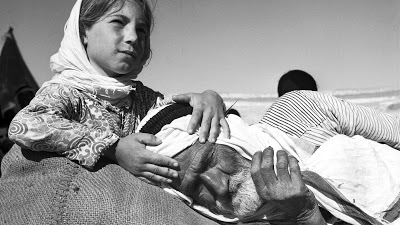

Arab women join men in battle inside of Jaffa gate, Jerusalem, March 31, 1948. Still from “1948: Creation & Catastrophe.” (Photo: courtesy of the filmmakers)

Dr. Hatem Bazian (L), Ahlam Muhtaseb (C), Andy Trimlett (R). (Photo: courtesy of the author)

Your film devotes a great deal of attention to the famous massacre that took place in the village of Deir Yassin. Were you able to discover anything new about this event?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: Yes, we did uncover some new details. By sheer coincidence, while in San Diego, I happened to meet a survivor of the massacre by the name of Azziz Akel. He introduced us to his brother Othman, also a survivor. We compiled a list of all the Palestinian survivors and their descendants in the United States. I interviewed several of them and transcribed the phone interviews. I had to acquire a book that had been published only in Arabic and translate it in order to check the facts.

Besides the testimony of survivors, did you learn anything new on the topic from the archives?

Andy Trimlett: There have been many attempts over the years by a variety of people to gain access to documents and photographs from Deir Yassin. All have failed. In 2006 Neta Shoshani, director of the film “Born in Deir Yassin,” went to the Israeli High Court of Justice to petition for the release of the Deir Yassin materials. The 50-year embargo on classified documents had officially ended, but the court extended the embargo to 2012.

We had an experienced Israeli researcher, also a documentary filmmaker, Rona Sela, on our team. In 2016, long after the embargo extension had expired, we asked Rona to try to get those documents. She was unable to find them in the archives and eventually filed an official request. In response, the state archivist informed us that the IDF Archive refuses to release those materials. They did, however, forward our request to the desk of the Minister of Justice, Ayelet Shaked. We have not heard back.

Nevertheless, you did amass a vast amount of archival material. And you conducted over 90 interviews in seven countries and three different languages. You could not possibly have used all this information in making the film. You had to be selective. Do (or will) other researchers have access to the unused material?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: Yes, we view this as an oral history project. The film is only one part of it. We have already started the process of cleaning up the interviews – removing extraneous noises, interruptions, and so on – and inserting subtitles with a view to posting them on our website (www.1948movie.com). This is costly because we have to hire a professional bilingual editor. But we have prepared the first 12 interviews and they will go up on the website very soon.

We have also uploaded our 19-page bibliography. We plan to share our notes file and to create interactive maps of the destroyed villages. As you can see, this is a massive project and we hope to go forward slowly but surely.

Palestinian boy on a school bus, still from “1948: Creation & Catastrophe.” (Photo: courtesy of the filmmakers)

Your website contains a number of reviews of the film. One of these reviews, reproduced from Middle East Eye, is by Dr. Hatim Kanaaneh, who has contributed several articles to Mondoweiss. He regrets that you do not cover more of the things that happened in the Nakba. In particular, he wishes that you had paid more attention to other less well-known massacres apart from that at Deir Yassin. I don’t think it would be fair to say that he criticizes you, because he realizes that there is a limit to the amount that a viewer can absorb in a single film. But he hopes there will be other documentaries that make good these omissions – for instance, about the Nakba in his native Galilee.

I made a quick search and did find a few films about particular aspects of the Nakba. One is Ramez Kazmouz’ “Lost Cities of Palestine: Haifa, Nazareth, and Jaffa,” an Al Jazeera World documentary available on Youtube. Hala Gabriel, who I also interviewed for Mondoweiss, will soon be releasing her film Road to Tantura – a village that was the site of another major massacre in 1948. But of course there are not enough such films.

Ahlam Muhtaseb: Even a thousand films on the Nakba would not suffice. The Palestinian national archives have been destroyed twice – first in 1948 and then again during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982 – and destruction of the Palestinian cultural and documentary legacy continues today. So there is an urgent need to produce more films, conduct more interviews, and collect more information.

Andy Trimlett: There are so many stories that we couldn’t fit into this documentary. For example, there is an incredible story from Farid Zraiq, who we interviewed in Eilaboun. He told us that he was lined up to be shot in the massacre at Eilaboun, but Israeli soldiers pulled him out of the line. They told him to drive a vehicle at the head of their convoy in case the road was mined. Eventually they let him go. But he soon found himself again lined up to be shot together with other young men in a little-known massacre at the village of Farradiyya. Somehow, however, he escaped death a second time.

Our documentary features moving personal stories from places and episodes throughout the war. But its main purpose is to try to convey a big-picture understanding of what happened in 1948. There are so many other ways to share this history – following the stories of individual towns or families, tracking the fate of the hundreds of Palestinian villages whose inhabitants fled, showing how 1948 has reverberated throughout the decades… I could go on.

The main challenge that anyone attempting to tell this story will face in the future is that we have lost so many of the people who lived these events. The interviews we conducted were the last ever given by many of the men and women in our documentary. The last eyewitnesses are passing away.

Film poster.

How many screenings has the film had so far? In which countries?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: The premiere of the first cut of the film was held on April 23, 2017 at the Arizona International Film Festival. Between November 2017 and January 2019 there were 45 screenings, in Dubai, Kuwait, Egypt, Israel, Italy, Britain, Australia, and Canada as well as the United States. A full list of screenings is at 1948movie.com/screenings.

Our film has been selected for screening in South Africa at next month’s conference Teaching Palestine: Pedagogical Praxis and the Indivisibility of Justice. Our film has also been officially selected for screening at the Festival Palestine en Vue 2019 in France in April.

Who held the screening in Israel? How did it go?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: The film was screened in December 2017 by the organization Zochrot as part of their annual 48mm Film Festival From Nakba to Return at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque and the Left Bank Cine Club. Zochrot (“remembering” in Hebrew) is an NGO that has worked since 2002 to persuade the Israeli-Jewish public to acknowledge and accept accountability for the ongoing injustices of the Nakba. They reported a very positive reception of the film, but this is a progressive group that is actually a partner of the BDS movement.

If someone wants to organize a new screening of the film how should they go about it?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: They can submit a request through our website, which will put them in touch with our friendly distributor, Michael Patrick Lilly, Chief Creative Officer at Factory Film Studio. We have a media kit and a screening discussion guide that they could use to plan their screening. They contain many tips and suggestions.

People who want to hold a screening in their community should go to 1948movie.com/host. Our distributor will respond with all the details.

Academics who want to order a copy for their school can visit 1948movie.com/educationalor look for it on kanopy, an on-demand streaming video platform for schools and public libraries.

Seeing that your film has been available for some time already, I am a bit puzzled by the fact that it is being released only now. What does this mean?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: Release means that it will now be available to the public for individuals to purchase. Up until now it has been available only for public screenings and educational licensing. Actually it was made available to the public three weeks ago on iTunes, but our distributor has treated iTunes sales as pre-release. From today the film will be available on many more platforms, including Amazon, Google Play, and the in-library service Hoopla. Later this month the film will premiere on Rogers Cable, Canada’s second largest cable video-on-demand (VOD) provider. Then in May it is due to be released on US cable VOD providers, including Dish TV, Comcast, InDemand, Verizon, and AT&T.

I learned from your website that the city of West Hollywood has “postponed” a screening and panel discussion of your film that had been scheduled for December 12, 2018 as part of a speaker series on human rights. Was it really just postponed or was it canceled altogether?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: The decision not to screen the film on December 12 was made under pressure from Zionist groups who, as usual, accused me of anti-Semitism. But following counter-protests by social justice activists, fellow academics, and other members of the local community the screening is now rescheduled for March 12. We have even received a letter of apology. We are extremely grateful for the incredible outpouring of support that we received. Professor Sandy Tolan’s article on Truthdig was especially powerful.

Have you experienced other similar cases? How can such pressure be neutralized? Do you intend to persist in trying to arrange screenings at venues open to the public?

Ahlam Muhtaseb: Yes, we have been attacked before, mainly because I am blacklisted by the notorious McCarthyism-style website Canary Mission. People have been copying and pasting their accusations without even seeing the film. There have been other attempts to prevent screenings, including at my own campus, by StandWithUs, another Zionist group that now attacks us at almost every screening. What is sad is that they attack the film without seeing it. We are persisting and we have succeeded in fighting racism and hatred.

Andy Trimlett: I would urge anyone who has heard that our documentary is anti-Semitic to take the time to see it. Yes, terrible events did take place in 1948, but in no way did we see our mission as being to demonize one side or the other. We set out to present the events of 1948 because it is so vital to understanding the conflict as a whole. We were keenly aware of the sensitivity of this subject, so accuracy was crucial to us. That is why we put so much of our lives into the project. We researched every story that was told in the film. We were very careful to show only images that matched the places and events we were describing, so if you are hearing a story about Jaffa you are seeing images of Jaffa. Above all, we worked extremely hard to treat everyone in this story with humanity and enable them to have their voices heard.