Settle for Nothing

Pete

Guest, Medium, June 5, 2018

After

millions marched in 2003 to protest the US-led invasion of Iraq, the ensuing

conflict dealt a forceful blow to the empowerment of the anti-war movement. It

was also the start of a worrying trend for governments to ignore the will of

their people.

One day

after Donald Trump took his oath of office, millions took to the streets of

more than 400 US towns and cities to protest. The ‘Women’s March,’ which began

as a demonstration to rage against Trump’s overt misogyny and anti-abortion

stance, evolved rapidly into a protest against the very fact of his presidency.

Trump’s first two weeks were always going to be a divisive theatre, but few

expected the new administration to follow through on its campaign pledges to

build a wall and shut its borders to the citizens of seven Muslim countries.

Once,

such howls of protest from the street would have led to reversals of policy,

but today there is no sense that the outcry has resonated at all in the White

House. With perhaps the most divisive president in modern American history now

in office, protest movements new and old are gearing up for four years of

running battles with the administration. But what can they really achieve if

Trump and his government aren’t listening?

Protest is

supposed to be a pressure valve for democratic society, and a way for the

people on the street to shape their politics outside of the electoral cycle. At

some point, in the democracies of the West, that mechanism has broken down.

Donald

Trump is more than just an anti-institutional candidate; his rise was a

many-headed hydra of unrestrained prejudice, blue-collar desperation, and an

American identity in crisis, all aided by the systematic undermining of the

basic rules of engagement in Western politics. But the anger against the

institutions of state that Trump tapped into as he rattled towards the White

House transcends political tribes, and it is rising — in part as a consequence of those same

institutions’ failure to listen to the drumbeat from the streets.

Jeffrey

Murer, lecturer on collective violence at St Andrews University and an expert

in protest, said that the turning point could have come more than a decade ago,

in 2003, when massive protests across Europe against the US-led invasion of

Iraq were ignored by politicians, who pressed ahead anyway.

“You see

literally millions of people marching across Europe and North America against

what was then the impending invasion of Iraq. And there was nothing doing. In

particular, in Britain, it was a profound moment, where it was the Labour Party

not listening to people on the street,” Murer says.

But in

the febrile years since the financial crisis, that feeling of distance has

metastasised into impotence, driving protest movements to try to enter the

political mainstream. In the US, Occupy Wall Street took on the banks that many

believed had caused the downturn, but had escaped without censure. In the UK, students

turned out en masse to argue against the imposition of tuition fees. In Greece,

Athens’ Syntagma Square was turned into a near-permanent battleground over

brutal cuts to social services during the country’s debt crisis, and what they

saw as the government’s desire to appease investors and international

institutions.

“I think

there was the idea that people in the street were asking for public health, for

utilities, for transportation, for heat, for electricity, and the priority

still was private banks,” Murer says.

That was

mirrored across Europe, and in the US, where the anger on the streets failed to

translate into meaningful reform. Faced with this failure, several protest

groups morphed into mainstream political — or anti-political — movements that are contesting elections or forcing

their way into the democratic process. In Italy, the Five Star

Movement,

led by the comedian Beppe Grillo, has moved from the street to the ballot box;

in Spain, the anti-austerity group, Podemos, snowballed from a group of radical

academics to become a genuine political force.

In the

US, the message and language of the Occupy movement echoed in the campaign that

turned the independent, radical senator Bernie Sanders into a credible challenger

for the Democratic Party’s nomination for president.

There was

considerable overlap between the UK’s anti-tuition fee marchers and those who

surged into the Labour Party to back the anti-establishment Jeremy Corbyn for

leader. But when Corbyn ‘relaunched’ himself for 2017, his language — at least on Twitter — started to mirror not Sanders, but

Trump, repeating over and over again that “the system” was “rigged”.

“Sometimes

protest movements that step into the formal electoral system do indeed find it

is rigged against them.”

In Hong

Kong, in September 2014, proposed changes to the electoral system brought

protesters, many of them students, onto the streets. They camped out in the

business district, channeling the US’ Occupy Wall Street to form Occupy

Central. As the standoff — and ultimately, clashes — with the police escalated, the umbrellas that many

carried became a symbol of the movement.

Those

protests were eventually dispersed, but they simmered all through 2015 and into

2016, occasionally boiling over into more confrontations. As the second

anniversary of the protests approached, though, many of those who had been at

the vanguard of the movement had to admit defeat. Beijing’s grip continued to

tighten, the Party-appointed chief executive, CY Leung, offered no concessions.

In the

words of one protester, who later became a candidate for a new political party

contesting Hong Kong’s September Legislative Council elections: “Occupy failed.

It achieved nothing.”

Even the

protesters that won seats found they were restricted in their ability to

exercise any kind of power; several have been challenged by the government and

face disqualification. Their foray into democracy seems to have done little but

widen the gap between the protests and the state.

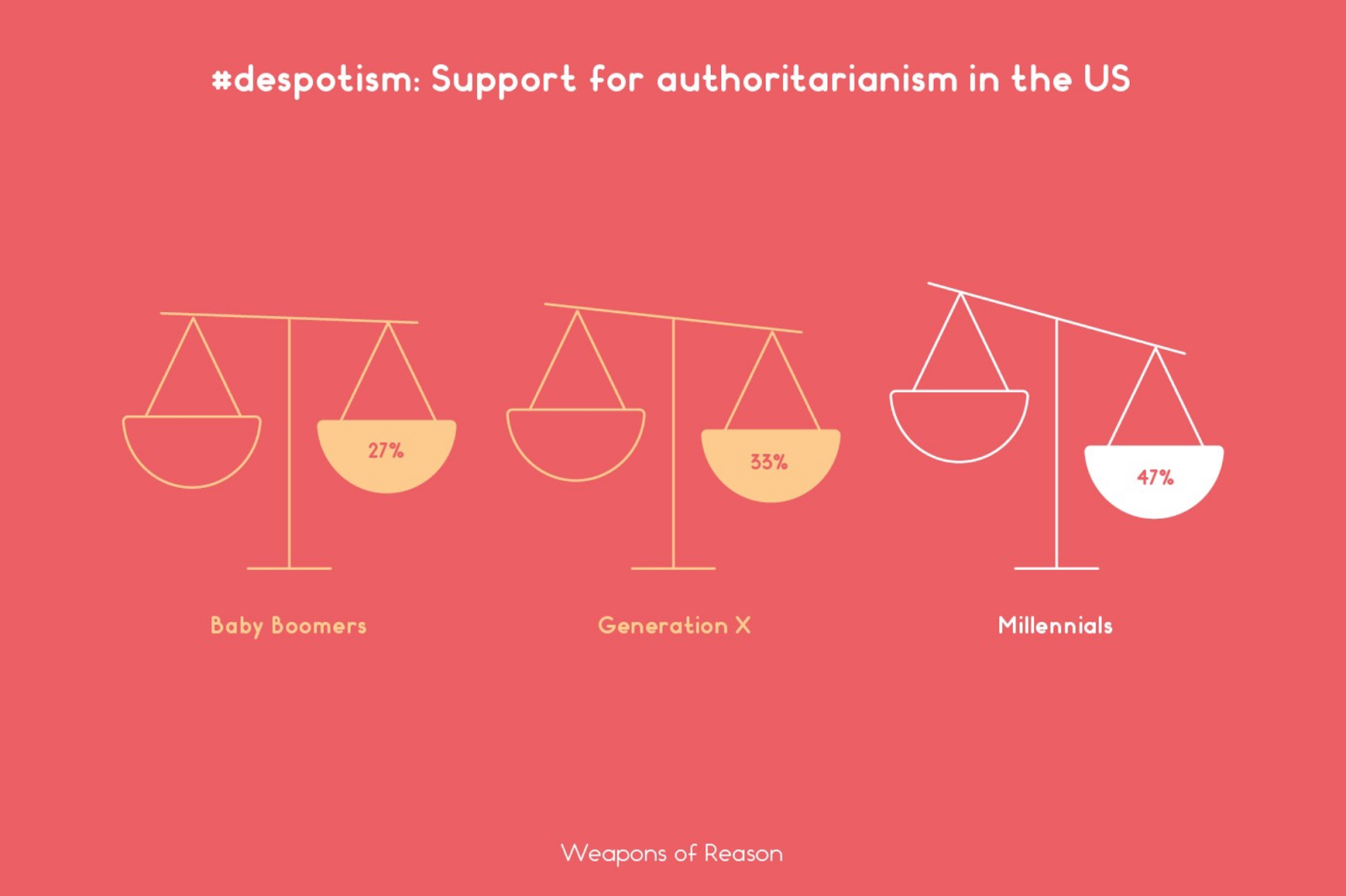

Worldwide,

people are finding that gap insurmountable, creating an odd dynamic between

formal democratic mechanisms and protest, made stranger by the fact that many

young people are apparently losing faith in democracy and in democratic

institutions. Recent research by two political scientists — Yascha Mounk from Harvard, and Roberto Stefan Foa

from the University of Melbourne — found that globally, younger

people are less convinced by the importance of democracy than their parents’

generation; they were also more accepting of authoritarian measures, such as

military control of governments.

Fewer

than 30% of Americans born since 1980 say that living in a democracy is

‘essential’; more than 20% born since 1970 say that the country’s democratic

system is ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’. Mounk and Foa observed the same patterns — a phenomenon that they call ‘democratic

deconsolidation’ — in the UK, the Netherlands,

Sweden, Australia, and New Zealand.

|

| Source: World Values Survey, USA, 2011. Percentage stating that “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections” was “Fairly Good” or “Very Good”. |

As Murer

said, it is hard to separate this loss of faith in democracy and democratic

institutions from the sense that government no longer listens, and that

protest’s power has dwindled.

“For the

most part, at least in my own research, I’ve found that a lot of young people

have very little regard for institutions in general,” says Murer. “They think

that those institutions don’t work, or are corrupt. In thinking so, they look

for alternate means of expression. Sometimes that’s through direct action,

sometimes that’s through protest or demonstrations. The idea that, to use the

term that Donald Trump keeps using, that the system is rigged, I think for a

lot of young people that feels like a great reality.

“We are

headed into uncharted territory of very new challenges for democratic

institutions, where we will really see how resilient they may be. Is there a

way for the voice of average people to stand up against the very entrenched

corporate interests that have now permeated Western politics… Or do we see

direct action groups themselves replace a kind of politics?”