She married 3 brothers in family torn by War

By Rod Nordland, Ny Times, May

26, 2018

Khadija’s

fate, at 18, has been to be widowed twice and passed down through a family deep

in Taliban territory. “I cannot talk about my dreams,” she says.

fate, at 18, has been to be widowed twice and passed down through a family deep

in Taliban territory. “I cannot talk about my dreams,” she says.

|

|

Khadija,

18, has married three brothers, losing two of them to the Afghan war.

“I do not

want this husband to be killed by the Taliban,” she said.

CreditErin Trieb for

The New York Times |

KABUL,

Afghanistan — Khadija is 18 now, just a year older than the Afghan war itself,

and she has already been married three times — to three brothers.

One was a

Taliban insurgent, killed fighting the United States Marines. One was a

policeman, killed fighting the Taliban. One was an interpreter for the Marines

who is now hunted by the Taliban, who have threatened to kill him and his

infant son.

Taliban insurgent, killed fighting the United States Marines. One was a

policeman, killed fighting the Taliban. One was an interpreter for the Marines

who is now hunted by the Taliban, who have threatened to kill him and his

infant son.

The story

of Khadija and the three brothers she married is an account of war and

tradition that is tragically Afghan. It encompasses the bitter arc of the

Afghan war in its most violent place, Helmand Province in the south, the Taliban stronghold where many families have been torn apart by

loyalties divided between the government and the insurgents.

of Khadija and the three brothers she married is an account of war and

tradition that is tragically Afghan. It encompasses the bitter arc of the

Afghan war in its most violent place, Helmand Province in the south, the Taliban stronghold where many families have been torn apart by

loyalties divided between the government and the insurgents.

It is

also the story of women in a traditional society struggling against the lack

also the story of women in a traditional society struggling against the lack

of choice

their culture gives them in their own lives. Their Pashtun society considers it

the duty of brothers to marry their brothers’ widows — and leaves those widows

with little choice but to obey, or lose their children and their homes.

their culture gives them in their own lives. Their Pashtun society considers it

the duty of brothers to marry their brothers’ widows — and leaves those widows

with little choice but to obey, or lose their children and their homes.

The

details from interviews with Khadija, who like most rural Afghan women has just

one name, and the family members were confirmed by local government and police

officials in Helmand.

details from interviews with Khadija, who like most rural Afghan women has just

one name, and the family members were confirmed by local government and police

officials in Helmand.

Khadija’s

journey began in a southern farm community called Marja, which was once one of

the Marines’ greatest successes,

but is now a conspicuous failure of the Afghan government. Farmers there

mostly cultivate opium poppy, and regularly pay taxes to the Taliban.

journey began in a southern farm community called Marja, which was once one of

the Marines’ greatest successes,

but is now a conspicuous failure of the Afghan government. Farmers there

mostly cultivate opium poppy, and regularly pay taxes to the Taliban.

Even

before she was born, Khadija was engaged to her first cousin, Zia Ul Haq. Their

fathers were brothers and farmers who lived near one another in Marja.

before she was born, Khadija was engaged to her first cousin, Zia Ul Haq. Their

fathers were brothers and farmers who lived near one another in Marja.

At age 6,

Khadija formally married Mr. Haq, who was 15 years older — although the

marriage would not be consummated until she reached age 11 or puberty, whichever

came first, the family said. Child marriage is illegal, but still widely

tolerated in Afghanistan.

Khadija formally married Mr. Haq, who was 15 years older — although the

marriage would not be consummated until she reached age 11 or puberty, whichever

came first, the family said. Child marriage is illegal, but still widely

tolerated in Afghanistan.

Before

that could happen, an American airstrike struck a nearby house where Taliban

insurgents were said to be hiding, in 2010. Shrapnel from the strike killed her

husband’s 8-year-old sister, Farida.

that could happen, an American airstrike struck a nearby house where Taliban

insurgents were said to be hiding, in 2010. Shrapnel from the strike killed her

husband’s 8-year-old sister, Farida.

Marja was

a Taliban hotbed then and the Marines were intent on subduing it. In those

days, casualties from airstrikes

were among the biggest killers of civilians in the Afghan war, and public anger

was running hot.

a Taliban hotbed then and the Marines were intent on subduing it. In those

days, casualties from airstrikes

were among the biggest killers of civilians in the Afghan war, and public anger

was running hot.

After the

attack, Mr. Haq joined the Taliban. “They brainwashed him,” said Mr. Haq’s

youngest brother, Shamsullah Shamsuddin, 19. “At first they forced him to join,

but then they persuaded him.”

attack, Mr. Haq joined the Taliban. “They brainwashed him,” said Mr. Haq’s

youngest brother, Shamsullah Shamsuddin, 19. “At first they forced him to join,

but then they persuaded him.”

From time

to time, their Taliban brother visited. But then it got hard to do so as more

Marines poured into Marja. The Americans arrived saying they would not only

destroy Taliban control, but would deliver a vaunted “government in a box,” providing services like schools and

electricity that the community sorely lacked.

to time, their Taliban brother visited. But then it got hard to do so as more

Marines poured into Marja. The Americans arrived saying they would not only

destroy Taliban control, but would deliver a vaunted “government in a box,” providing services like schools and

electricity that the community sorely lacked.

A year

went by with no word from Khadija’s husband until one night a Taliban

delegation came with his body wrapped in a shroud — his shoulder blown off from

a gunshot wound, one of many — and turned it over to the family.

went by with no word from Khadija’s husband until one night a Taliban

delegation came with his body wrapped in a shroud — his shoulder blown off from

a gunshot wound, one of many — and turned it over to the family.

Khadija

was a widow at age 10.

was a widow at age 10.

Two of

Mr. Haq’s other brothers became policemen, because the pay was good and there

was little alternative employment in the middle of war.

Mr. Haq’s other brothers became policemen, because the pay was good and there

was little alternative employment in the middle of war.

|

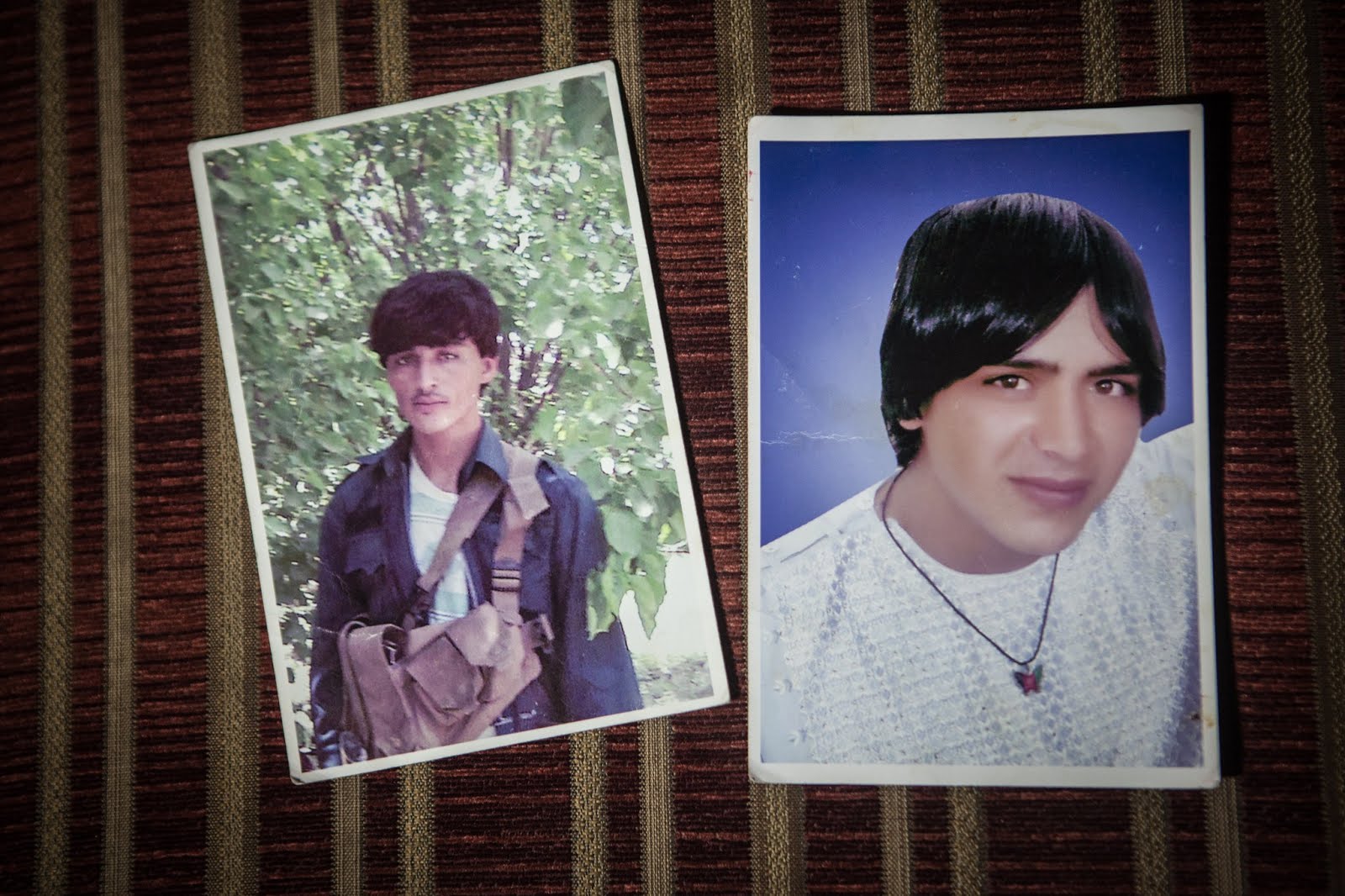

| Aminullah, left, and Hayatullah were brothers of Khadija’s first husband. Both joined the police, and both were killed. Khadija had married Aminullah after his brother’s death.CreditErin Trieb for The New York Times |

Khadija

then married one of them: Mr. Haq’s next oldest brother, Aminullah. It was her

father’s decision, and she said she knew she had no choice in the matter.

then married one of them: Mr. Haq’s next oldest brother, Aminullah. It was her

father’s decision, and she said she knew she had no choice in the matter.

Aminullah,

22, was fabled as a fighter with the Afghan police, his family members said.

“He could handle every kind of heavy weapon, and the Taliban were afraid of

him,” Mr. Shamsuddin said.

22, was fabled as a fighter with the Afghan police, his family members said.

“He could handle every kind of heavy weapon, and the Taliban were afraid of

him,” Mr. Shamsuddin said.

Khadija

raves about Aminullah, too. “He promised when he came home that I could remove

my burqa, and he was going to bring me good clothes, and we would have a good

life,” she said. “He was a good man, and a good husband.”

raves about Aminullah, too. “He promised when he came home that I could remove

my burqa, and he was going to bring me good clothes, and we would have a good

life,” she said. “He was a good man, and a good husband.”

He was

also fiercely devoted to the government’s cause, just the opposite of his

Taliban brother, Khadija said. “He would say, ‘I will never leave my country to

them, as long as there is blood in my body, I will fight them.’ Whenever he

went out, I was always watching the door until he came back.”

also fiercely devoted to the government’s cause, just the opposite of his

Taliban brother, Khadija said. “He would say, ‘I will never leave my country to

them, as long as there is blood in my body, I will fight them.’ Whenever he

went out, I was always watching the door until he came back.”

“I lost

him and I was thinking, ‘How could this happen to me?’ But it is God’s

decision, so I can say nothing.”

She was

pregnant with their daughter when Aminullah did not come back, in 2014. He was

killed on the highway by a roadside bomb. The Taliban were so delighted, Mr. Shamsuddin

said, that they slaughtered sheep in celebration, distributing the meat to

their neighborhood in Marja.

pregnant with their daughter when Aminullah did not come back, in 2014. He was

killed on the highway by a roadside bomb. The Taliban were so delighted, Mr. Shamsuddin

said, that they slaughtered sheep in celebration, distributing the meat to

their neighborhood in Marja.

“I lost

him and I was thinking, ‘How could this happen to me?” she said. “But it is

God’s decision, so I can say nothing.”

him and I was thinking, ‘How could this happen to me?” she said. “But it is

God’s decision, so I can say nothing.”

Mr.

Shamsuddin said that the family fled Marja and moved to Lashkar Gah, the

provincial capital. After they left, the Taliban burned down their old house,

he said.

Shamsuddin said that the family fled Marja and moved to Lashkar Gah, the

provincial capital. After they left, the Taliban burned down their old house,

he said.

At age

14, Khadija gave birth to her daughter, Roqia, a few months later. After

waiting the Quranic-stipulated four months and 10 days after Aminullah’s death,

Khadija married Mr. Shamsuddin, the youngest brother, in 2015.

14, Khadija gave birth to her daughter, Roqia, a few months later. After

waiting the Quranic-stipulated four months and 10 days after Aminullah’s death,

Khadija married Mr. Shamsuddin, the youngest brother, in 2015.

Years

before, probably when he was around 14, though he is hazy on the dates, Mr.

Shamsuddin had begun hanging around the Marines’ base in Marja and quickly

picked up English from the troops. Soon they hired him as an interpreter, for

the comparatively princely sum of $25 a day.

before, probably when he was around 14, though he is hazy on the dates, Mr.

Shamsuddin had begun hanging around the Marines’ base in Marja and quickly

picked up English from the troops. Soon they hired him as an interpreter, for

the comparatively princely sum of $25 a day.

That job

ended when the Marines left Afghanistan in 2013. Today, Mr. Shamsuddin earns $5

a day as a rickshaw driver in Lashkar Gah and is the sole support for both his own growing

family and his extended family, with at least half a dozen members.

ended when the Marines left Afghanistan in 2013. Today, Mr. Shamsuddin earns $5

a day as a rickshaw driver in Lashkar Gah and is the sole support for both his own growing

family and his extended family, with at least half a dozen members.

Gul Juma,

Mr. Shamsuddin’s mother, now has only three children left of her 11. Two young

sons died of disease, and her 21-year-old son, Hayatullah, also a policeman,

was killed in a so-called blue on blue, or insider, attack by a Taliban infiltrator, only a few months before

Aminullah’s death.

Mr. Shamsuddin’s mother, now has only three children left of her 11. Two young

sons died of disease, and her 21-year-old son, Hayatullah, also a policeman,

was killed in a so-called blue on blue, or insider, attack by a Taliban infiltrator, only a few months before

Aminullah’s death.

Mr.

Shamsuddin is her last surviving son.

Shamsuddin is her last surviving son.

He is

proud that he is not, as he put it, “a typical Pashtun man.” When Khadija’s

father, his uncle, proposed that Khadija marry him, Mr. Shamsuddin said the

decision was up to her.

proud that he is not, as he put it, “a typical Pashtun man.” When Khadija’s

father, his uncle, proposed that Khadija marry him, Mr. Shamsuddin said the

decision was up to her.

“We

didn’t force her to marry me, although we could have,” he said. “I had the

ambition to marry someone else, but she was my brother’s widow, so I had no

choice.”

didn’t force her to marry me, although we could have,” he said. “I had the

ambition to marry someone else, but she was my brother’s widow, so I had no

choice.”

Khadija

was listening as Mr. Shamsuddin said it, and responded, politely, that it was

not quite like that. “Uncle’s Son did not force me to marry him,” she said

using a polite term for her husband, “but under Pashtun culture, I had no other

choice.”

was listening as Mr. Shamsuddin said it, and responded, politely, that it was

not quite like that. “Uncle’s Son did not force me to marry him,” she said

using a polite term for her husband, “but under Pashtun culture, I had no other

choice.”

“Once, I

wanted to study and be an educated woman who could stand on my own two feet,

but in my culture it is not possible.”

Widows

cannot work, like most women in traditional areas, and any inheritance or

property would go to her husband’s brothers, not to his widow or children.

cannot work, like most women in traditional areas, and any inheritance or

property would go to her husband’s brothers, not to his widow or children.

She and

Mr. Shamsuddin have a son together now, Sayed Rahman, 1. The Taliban have Mr.

Shamsuddin’s phone number and often call him, he said. “They say they will kill

me and then kill Sayed Rahman,” he said.

Mr. Shamsuddin have a son together now, Sayed Rahman, 1. The Taliban have Mr.

Shamsuddin’s phone number and often call him, he said. “They say they will kill

me and then kill Sayed Rahman,” he said.

|

|

Shamsullah

and Khadija, their son, Sayed Rahman, 1, and Shamsullah’s mother,

Gul Juma, in

Kabul in April.CreditErin Trieb for The New York Times |

Khadija

and Mr. Shamsuddin spoke frankly about their disappointments, though they

showed no bitterness toward each other.

and Mr. Shamsuddin spoke frankly about their disappointments, though they

showed no bitterness toward each other.

“My wife

is very strong. Some lesser person would not have survived what she has

survived,” Mr. Shamsuddin said. “She is not expecting very much from me;

financially I don’t have much to give her, just good words and good behavior.

Even though I believe men should beat women when they don’t listen, I have

never had to beat her. I guess I give her respect even more because of my

brothers.”

is very strong. Some lesser person would not have survived what she has

survived,” Mr. Shamsuddin said. “She is not expecting very much from me;

financially I don’t have much to give her, just good words and good behavior.

Even though I believe men should beat women when they don’t listen, I have

never had to beat her. I guess I give her respect even more because of my

brothers.”

Mr.

Shamsuddin said it is a sad responsibility, marrying the wife of a dead

brother. “When you look at her, you always see your brother,” he said.

Shamsuddin said it is a sad responsibility, marrying the wife of a dead

brother. “When you look at her, you always see your brother,” he said.

It was a

sadness for Khadija, too.

sadness for Khadija, too.

“Once I

had dreams, but I cannot talk about my dreams with anyone, because I am a

woman,” she said. “Once I wanted to study and be an educated woman who could

stand on my own two feet, but in my culture it is not possible. Now my biggest

dream is that I do not want this husband to be killed by the Taliban. I ask God

to protect him.”

had dreams, but I cannot talk about my dreams with anyone, because I am a

woman,” she said. “Once I wanted to study and be an educated woman who could

stand on my own two feet, but in my culture it is not possible. Now my biggest

dream is that I do not want this husband to be killed by the Taliban. I ask God

to protect him.”

Mr.

Shamsuddin also had his dreams. He earned a lot of money working for the

Marines, before his marriage, and through intermediaries he had approached the

father of a woman named Halima to marry her. The father had approved the match.

Shamsuddin also had his dreams. He earned a lot of money working for the

Marines, before his marriage, and through intermediaries he had approached the

father of a woman named Halima to marry her. The father had approved the match.

Then,

suddenly, the Marines were gone, he was jobless, his brother was dead. He married

Khadija; Halima married another policeman.

suddenly, the Marines were gone, he was jobless, his brother was dead. He married

Khadija; Halima married another policeman.

“I told

my wife about Halima, because we both shared the same destiny in a way: We

couldn’t choose who we ended up with. Sometimes she teases me if we have an

argument, ‘Oh, you love Halima too much.’”

my wife about Halima, because we both shared the same destiny in a way: We

couldn’t choose who we ended up with. Sometimes she teases me if we have an

argument, ‘Oh, you love Halima too much.’”

It is not

exactly that Mr. Shamsuddin does not love Khadija. “She is beautiful enough for

me, and as a person I like her,” he said. “We are like friends, we have fun

together, tease each other. But love? We are happy with each other so you could

say I love her. But I was severely in love with Halima. When I think of her I

get a pain in my heart.” He beat his chest there with his fist, twice.

exactly that Mr. Shamsuddin does not love Khadija. “She is beautiful enough for

me, and as a person I like her,” he said. “We are like friends, we have fun

together, tease each other. But love? We are happy with each other so you could

say I love her. But I was severely in love with Halima. When I think of her I

get a pain in my heart.” He beat his chest there with his fist, twice.

Khadija

described much the same feeling for her late husband Aminullah. “No man has

ever kissed me but him,” she said. “Now I can only kiss my son.” When she

thinks about Aminullah, breathing becomes difficult, she said. “I cry when I’m

alone.”

described much the same feeling for her late husband Aminullah. “No man has

ever kissed me but him,” she said. “Now I can only kiss my son.” When she

thinks about Aminullah, breathing becomes difficult, she said. “I cry when I’m

alone.”

“If he

joins the police, I am sure the Taliban will kill him in two or three months.”

Earlier

this year, Halima’s policeman husband was killed by the Taliban. Mr. Shamsuddin

then wanted to take her as a second wife, and he said Halima was open to it. “I

just don’t have enough money to take care of a second wife, that’s the only problem.

And of course I would have to discuss it with my wife and my mother.”

this year, Halima’s policeman husband was killed by the Taliban. Mr. Shamsuddin

then wanted to take her as a second wife, and he said Halima was open to it. “I

just don’t have enough money to take care of a second wife, that’s the only problem.

And of course I would have to discuss it with my wife and my mother.”

So now he

plans to join the police force in Helmand, as his brothers did. The pay is four

or five times as much as what he earns with his rickshaw. Casualty rates are

much higher among Afghan

policemen than soldiers or other security forces, and those rates

are highest of all in Helmand Province. But he might earn enough to afford to

marry Halima.

plans to join the police force in Helmand, as his brothers did. The pay is four

or five times as much as what he earns with his rickshaw. Casualty rates are

much higher among Afghan

policemen than soldiers or other security forces, and those rates

are highest of all in Helmand Province. But he might earn enough to afford to

marry Halima.

As Mr.

Shamsuddin spoke of this, his wife and mother were in the other room. Had he

told them of his police plans? “I didn’t tell my mother or my wife: Men should

not be sharing such decisions with women,” Mr. Shamsuddin said. “I’ll tell them

after.”

Shamsuddin spoke of this, his wife and mother were in the other room. Had he

told them of his police plans? “I didn’t tell my mother or my wife: Men should

not be sharing such decisions with women,” Mr. Shamsuddin said. “I’ll tell them

after.”

|

| Shamsullah plans to join the police force in Helmand Province, as his brothers did. But, he said, “I didn’t tell my mother or my wife.”CreditErin Trieb for The New York Times |

Afterward

the women went off by themselves, talking to female visitors, including a Times

journalist. “I know he wants to join the police, but we will never allow him,”

Khadija said. “If he joins the police, I am sure the Taliban will kill him in

two or three months. And after that, what can we do? Who is going to protect

this small baby?”

Khadija

scoffed at the talk of Mr. Shamsuddin’s marrying Halima, which she was also

aware of.

scoffed at the talk of Mr. Shamsuddin’s marrying Halima, which she was also

aware of.

“Uncle’s

Son could never marry her,” she said. “She has 10 brothers-in-law, and they

would never allow her to marry outside their family. He is dreaming.”

Son could never marry her,” she said. “She has 10 brothers-in-law, and they

would never allow her to marry outside their family. He is dreaming.”