The unspeakable cruelty of El Salvador’s abortion laws

Lisa

Kowalchuk, The conversation, April 11, 2018

Kowalchuk, The conversation, April 11, 2018

Around

the world today we are seeing two opposite tendencies in abortion law reform.

the world today we are seeing two opposite tendencies in abortion law reform.

|

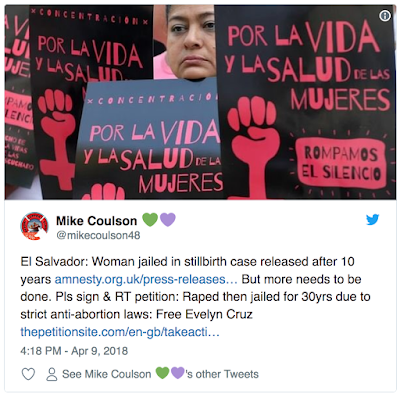

| Women protest outside a courtroom in San Salvador in 2017, demanding the government free women prisoners who are serving 30-year prison sentences for having an abortion. (AP Photo/Salvador Melendez) |

In the

Americas, the governments of Bolivia,

Chile

and Mexico City recently lifted total bans on abortion. Other jurisdictions such as Ohio,

several states in Mexico and Poland

have passed or attempted tighter restrictions.

Even Doug

Ford, the leader of Ontario’s Progressive Conservative party, has voiced

openness to making abortion more difficult to access.

Ford, the leader of Ontario’s Progressive Conservative party, has voiced

openness to making abortion more difficult to access.

In El

Salvador, the clock is

ticking towards a May 1, 2018, deadline for reform that would

decriminalize abortion in two situations: When the life of the pregnant woman

is in danger and when an underage girl (but not an adult woman) becomes

pregnant through rape.

Salvador, the clock is

ticking towards a May 1, 2018, deadline for reform that would

decriminalize abortion in two situations: When the life of the pregnant woman

is in danger and when an underage girl (but not an adult woman) becomes

pregnant through rape.

The

attention of the world’s media was recently drawn to this country’s extreme

abortion regime by the commutations

of the 30-year prison sentences of two Salvadoran women. Their crime

was to have had a miscarriage. Both innocent women had served over a decade of

their sentences.

attention of the world’s media was recently drawn to this country’s extreme

abortion regime by the commutations

of the 30-year prison sentences of two Salvadoran women. Their crime

was to have had a miscarriage. Both innocent women had served over a decade of

their sentences.

To

understand what is at stake, we need to look at what makes El Salvador probably

the worst country on earth to have an unwanted or life-threatening pregnancy,

or a complicated miscarriage, especially if you are poor.

understand what is at stake, we need to look at what makes El Salvador probably

the worst country on earth to have an unwanted or life-threatening pregnancy,

or a complicated miscarriage, especially if you are poor.

I am a sociologist who has researched

health-care policy in El Salvador, including the expansion of

health-care services to the poor by the left-of-centre Farabundo Martí National

Liberation Front (FMLN) government.

health-care policy in El Salvador, including the expansion of

health-care services to the poor by the left-of-centre Farabundo Martí National

Liberation Front (FMLN) government.

As an

admirer of this government’s goals and achievements in health care, I am struck

by a contradiction: It has made genuine efforts to reduce maternal mortality

but during most of its nine years in office, it has failed to challenge a law

that may actually increase it.

admirer of this government’s goals and achievements in health care, I am struck

by a contradiction: It has made genuine efforts to reduce maternal mortality

but during most of its nine years in office, it has failed to challenge a law

that may actually increase it.

The

problem is not just the abortion ban itself, which El Salvador shares in common

with five other

Latin American and Caribbean nations.

problem is not just the abortion ban itself, which El Salvador shares in common

with five other

Latin American and Caribbean nations.

What has

made El Salvador unique on the international stage is the fanatical

over-application of the law by police, prosecutors and judges. And the

complicity of many doctors fearful of standing on the wrong side of the law.

made El Salvador unique on the international stage is the fanatical

over-application of the law by police, prosecutors and judges. And the

complicity of many doctors fearful of standing on the wrong side of the law.

An

extreme law zealously over-applied

extreme law zealously over-applied

Abortion

was made illegal in El Salvador in all circumstances in 1997.

was made illegal in El Salvador in all circumstances in 1997.

This was

reinforced two years later by a Constitutional amendment declaring that life

begins at conception.

reinforced two years later by a Constitutional amendment declaring that life

begins at conception.

Among the

small number of countries that maintain a complete ban, only in El Salvador has

law enforcement led to women being sent to prison for 30 to 40 years. To date more than 150

women and girls have been prosecuted. More than 28 women are

currently serving out cruelly long sentences.

small number of countries that maintain a complete ban, only in El Salvador has

law enforcement led to women being sent to prison for 30 to 40 years. To date more than 150

women and girls have been prosecuted. More than 28 women are

currently serving out cruelly long sentences.

|

| In this December 2017 photo, Salvadoran Teodora Vasquez, found guilty of what the court said was an illegal abortion via a miscarriage, arrives in a courtroom to appeal her 30-year prison sentence. (AP Photo/Salvador Melendez) |

The

country’s penal code mandates a 12-year sentence for women convicted of having

an abortion. But if a miscarried or stillborn fetus is deemed viable by the

courts, women are

prosecuted for aggravated homicide.

In one

case, a 40-year

prison term was handed to a woman who miscarried at 18 weeks.

case, a 40-year

prison term was handed to a woman who miscarried at 18 weeks.

Many women

jailed for miscarriages did not even know they were pregnant.

jailed for miscarriages did not even know they were pregnant.

Women

have been criminalized

for obstetric emergencies because judges accept contradictory or non-existent

evidence that they intended to either end the pregnancy or kill an

early-term fetus.

have been criminalized

for obstetric emergencies because judges accept contradictory or non-existent

evidence that they intended to either end the pregnancy or kill an

early-term fetus.

It is

precisely the flimsiness of these cases that has enabled sentences to

eventually be overturned through strenuous efforts of organizations like the Citizens’ Coalition for the

Decriminalization of Abortion.

precisely the flimsiness of these cases that has enabled sentences to

eventually be overturned through strenuous efforts of organizations like the Citizens’ Coalition for the

Decriminalization of Abortion.

Harms to

health

health

In

addition to this clear violation of women’s civil rights, the extremist

application of the law imposes harms to health and life.

addition to this clear violation of women’s civil rights, the extremist

application of the law imposes harms to health and life.

For

example, Salvadoran doctors have refused to intervene medically when a

pregnancy endangers a woman’s life, as in the case of ectopic pregnancy. This

is when a fertilized egg becomes lodged in the fallopian tube, leading to

rupture and lethal internal bleeding if untreated. In such cases doctors have

stood by until the tube ruptures.

example, Salvadoran doctors have refused to intervene medically when a

pregnancy endangers a woman’s life, as in the case of ectopic pregnancy. This

is when a fertilized egg becomes lodged in the fallopian tube, leading to

rupture and lethal internal bleeding if untreated. In such cases doctors have

stood by until the tube ruptures.

There are

particular harms for very young girls and teens. Girls as

young as nine years old have been denied therapeutic abortion.

particular harms for very young girls and teens. Girls as

young as nine years old have been denied therapeutic abortion.

For these

children, the trauma of sexual violence is compounded by the physical risks

that childbirth poses to an immature body and the terror of going through with

a dangerous pregnancy.

children, the trauma of sexual violence is compounded by the physical risks

that childbirth poses to an immature body and the terror of going through with

a dangerous pregnancy.

Three out of

every eight maternal deaths in El Salvador are pregnant teens who take their

own lives.

every eight maternal deaths in El Salvador are pregnant teens who take their

own lives.

It is

also known that 13 per cent

of maternal deaths in less developed countries are caused by unsafe

abortions, which in turn become more frequent when abortion is illegal or

unavailable.

also known that 13 per cent

of maternal deaths in less developed countries are caused by unsafe

abortions, which in turn become more frequent when abortion is illegal or

unavailable.

Hundreds

of clandestine abortions certainly continue to occur each year in El Salvador

despite the ban. Health Ministry officials themselves acknowledge

that the law and its application undermine their efforts to reduce the maternal

mortality rate.

of clandestine abortions certainly continue to occur each year in El Salvador

despite the ban. Health Ministry officials themselves acknowledge

that the law and its application undermine their efforts to reduce the maternal

mortality rate.

Government-employed

doctors and poor women

doctors and poor women

What

makes this situation all the more poignant is that it only affects the poor and

poorly educated.

makes this situation all the more poignant is that it only affects the poor and

poorly educated.

These

women and girls can’t afford care in private hospitals and clinics where

doctors maintain patient confidentiality. Nor can they afford good legal

counsel.

women and girls can’t afford care in private hospitals and clinics where

doctors maintain patient confidentiality. Nor can they afford good legal

counsel.

Hand in

hand with this class bias is most

prosecutions of women for suspected abortion originate from doctors in

state-funded, public hospitals. Since the public system doesn’t

charge for services, it is the only option for low-income Salvadorans.

hand with this class bias is most

prosecutions of women for suspected abortion originate from doctors in

state-funded, public hospitals. Since the public system doesn’t

charge for services, it is the only option for low-income Salvadorans.

It is

also where there are more early-career

doctors who don’t want to jeopardize their futures; these doctors

fear that not reporting could be seen as assisting in an abortion, which for

health professionals carries a penalty of six to 12 years.

also where there are more early-career

doctors who don’t want to jeopardize their futures; these doctors

fear that not reporting could be seen as assisting in an abortion, which for

health professionals carries a penalty of six to 12 years.

Prospects

for change

for change

Taken

together, the deprivations of liberty and the physical and psychological

suffering that have resulted from El Salvador’s abortion regime have been

labelled torture by Amnesty International.

together, the deprivations of liberty and the physical and psychological

suffering that have resulted from El Salvador’s abortion regime have been

labelled torture by Amnesty International.

The

outcome of the abortion struggle in the political arena is highly uncertain.

outcome of the abortion struggle in the political arena is highly uncertain.

On the

one hand, almost 60 per cent

of Salvadorans now favour loosening the law when a woman’s life is

in danger, and fully 79 per cent when the fetus is not medically viable.

one hand, almost 60 per cent

of Salvadorans now favour loosening the law when a woman’s life is

in danger, and fully 79 per cent when the fetus is not medically viable.

As well,

a tentative coalition emerged among legislators in late 2017 in favour of a bill by a

maverick Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) party member

proposing abortion be allowed in very limited circumstances.

a tentative coalition emerged among legislators in late 2017 in favour of a bill by a

maverick Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) party member

proposing abortion be allowed in very limited circumstances.

On the

other hand, most of these lawmakers will be replaced on May 1, 2018 and ARENA

overall remains staunchly opposed to any liberalization of the law. The party

will have a large plurality of seats in the Legislative Assembly, dwarfing all

the others.

other hand, most of these lawmakers will be replaced on May 1, 2018 and ARENA

overall remains staunchly opposed to any liberalization of the law. The party

will have a large plurality of seats in the Legislative Assembly, dwarfing all

the others.

ARENA,

moreover, has used abortion to villainize

the FMLN, which has responded at times by sacrificing

women’s interests for success at the polls.

moreover, has used abortion to villainize

the FMLN, which has responded at times by sacrificing

women’s interests for success at the polls.

But

whatever legislators decide in the coming days, a broad

social movement for fundamental justice on this issue has created momentum for

change that will not likely subside.

whatever legislators decide in the coming days, a broad

social movement for fundamental justice on this issue has created momentum for

change that will not likely subside.