More than one in 100 Nunavut infants have TB

Sarah

Giles, The Conversation, April 8, 2018

Canada’s

simmering tuberculosis (TB) outbreak in northern communities is likely much

worse than suspected.

simmering tuberculosis (TB) outbreak in northern communities is likely much

worse than suspected.

|

|

Tuberculosis

has been a problem for decades among Canada’s northern

Indigenous population.

New data obtained through access to information requests

reveals shockingly

high TB rates among Nunavut’s infants. Poor data collection

indicates the real

rates will be even higher. (Gar Lunney/Library and Archives Canada) |

A report newly obtained through an

access-to-information (ATI) request reveals that the incidence rate

of TB among Nunavut’s infants (under one year of age) was 1,020 cases per

100,000 people in 2017 — a shockingly high level.

access-to-information (ATI) request reveals that the incidence rate

of TB among Nunavut’s infants (under one year of age) was 1,020 cases per

100,000 people in 2017 — a shockingly high level.

In the

rest of Canada, the rate is just three infants

per 100,000.

rest of Canada, the rate is just three infants

per 100,000.

Worse,

the actual rate may be higher than the report indicates, as it drew only on

data from the first nine months of 2017. An additional 21 cases of TB (in

people of unknown ages) were identified before the year ended. Many important

data points were never collected.

the actual rate may be higher than the report indicates, as it drew only on

data from the first nine months of 2017. An additional 21 cases of TB (in

people of unknown ages) were identified before the year ended. Many important

data points were never collected.

Despite

these concerning numbers, Minister of Health Ginette Petipas Taylor, Minister

of Indigenous Services Jane Philpott and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK)

president Natan Obed recently announced the ambitious goal of eliminating TB

from Canada’s North by 2030.

these concerning numbers, Minister of Health Ginette Petipas Taylor, Minister

of Indigenous Services Jane Philpott and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK)

president Natan Obed recently announced the ambitious goal of eliminating TB

from Canada’s North by 2030.

While it

is commendable to see political will and $27.5 million

over five years supporting TB elimination, similar

announcements for TB reduction were made by federal ministers of health in 1997

and 2006. These targets were not met.

is commendable to see political will and $27.5 million

over five years supporting TB elimination, similar

announcements for TB reduction were made by federal ministers of health in 1997

and 2006. These targets were not met.

The main

hope arising from the latest plan is that ITK, a

non-profit organization advancing the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada,

is leading the process for the first time.

hope arising from the latest plan is that ITK, a

non-profit organization advancing the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada,

is leading the process for the first time.

Hard to

diagnose in babies

diagnose in babies

I work as

a family and emergency room doctor in the Northwest Territories. I also have a

diploma in tropical medicine and hygiene and I do work with Doctors without Borders.

a family and emergency room doctor in the Northwest Territories. I also have a

diploma in tropical medicine and hygiene and I do work with Doctors without Borders.

I have

seen the devastation that TB reaps. I am concerned by the high incidence rate

of TB in Nunavut’s babies. The poor data we have indicate that TB is a bigger

problem than the current numbers reveal.

seen the devastation that TB reaps. I am concerned by the high incidence rate

of TB in Nunavut’s babies. The poor data we have indicate that TB is a bigger

problem than the current numbers reveal.

Eliminating

TB in the North in just 12 years may be harder than many imagine.

TB in the North in just 12 years may be harder than many imagine.

|

|

Inuit

Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) President Natan Obed addresses media in Ottawa

on

Oct.5, 2017, while Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott (left) and Health Minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor (centre) look on. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick |

While

most people think of TB as a bacterial disease of the lungs found in

resource-poor countries, it can also present virtually anywhere in the body,

especially in infants.

most people think of TB as a bacterial disease of the lungs found in

resource-poor countries, it can also present virtually anywhere in the body,

especially in infants.

TB is

particularly hard to

diagnose in babies because the symptoms — of poor

weight gain, lack of playfulness and fever — are not very specific.

particularly hard to

diagnose in babies because the symptoms — of poor

weight gain, lack of playfulness and fever — are not very specific.

In

general, only affluent countries with excellent health care can definitely

diagnose babies through technical and expensive tests and, even then, many

cases are missed.

general, only affluent countries with excellent health care can definitely

diagnose babies through technical and expensive tests and, even then, many

cases are missed.

It is

difficult to know the true extent of tuberculosis in babies throughout the

world, but it is patently unacceptable for one in 100 babies in Nunavut to have

active TB.

difficult to know the true extent of tuberculosis in babies throughout the

world, but it is patently unacceptable for one in 100 babies in Nunavut to have

active TB.

A legacy

of fear and stigma

of fear and stigma

Tuberculosis

has been present in the area now known as Nunavut for more than 100

years but it has not always been so prevalent. As recently as 1997,

the incidence was 31 cases per

100,000.

has been present in the area now known as Nunavut for more than 100

years but it has not always been so prevalent. As recently as 1997,

the incidence was 31 cases per

100,000.

TB has

once again become an everyday reality for the people of Nunavut — due to the

Public Health Agency of Canada’s premature

closure of TB control programs like the Canadian Tuberculosis

Committee and its Aboriginal Scientific Tuberculosis Subcommittee in 2011, the

dramatic under-funding

of Indigenous health care, poor social

determinants of health and a lack of human

resources in the health-care field.

once again become an everyday reality for the people of Nunavut — due to the

Public Health Agency of Canada’s premature

closure of TB control programs like the Canadian Tuberculosis

Committee and its Aboriginal Scientific Tuberculosis Subcommittee in 2011, the

dramatic under-funding

of Indigenous health care, poor social

determinants of health and a lack of human

resources in the health-care field.

The

historical context of the treatment of Inuit with suspected TB cannot be

understated. During the

1940s through the 1960s, thousands of Inuit people thought to have TB were taken

from their villages and sent to sanitoriums in places like Hamilton, Ont.

historical context of the treatment of Inuit with suspected TB cannot be

understated. During the

1940s through the 1960s, thousands of Inuit people thought to have TB were taken

from their villages and sent to sanitoriums in places like Hamilton, Ont.

Most

never had a chance to say goodbye to their families and many never returned.

never had a chance to say goodbye to their families and many never returned.

A legacy

of fear and the

stigma of a communicable disease in small towns continues to deter

people from seeking medical help today.

of fear and the

stigma of a communicable disease in small towns continues to deter

people from seeking medical help today.

Lifelong

cognitive impairment

cognitive impairment

A person

exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria will usually not develop the

disease. Some, however, will only

partially fight off infection and will develop latent TB. Of those

with latent TB, five to 10 per cent will go on to develop symptoms of the disease,

or active TB.

exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria will usually not develop the

disease. Some, however, will only

partially fight off infection and will develop latent TB. Of those

with latent TB, five to 10 per cent will go on to develop symptoms of the disease,

or active TB.

Those with weakened

immune systems and babies are at heightened risk of developing

active TB.

immune systems and babies are at heightened risk of developing

active TB.

Active TB

is a potentially deadly infection and, if in the lungs, is contagious. People

exposed to the disease can receive preventative treatment to decrease their

risk of developing it.

is a potentially deadly infection and, if in the lungs, is contagious. People

exposed to the disease can receive preventative treatment to decrease their

risk of developing it.

Though

infants in Nunavut receive a TB vaccine at

birth, it is not entirely

protective.

infants in Nunavut receive a TB vaccine at

birth, it is not entirely

protective.

The high

incidence rate of TB among Nunavut’s infants is especially worrisome given that

Nunavut has the highest

fertility rate in the country, with women giving birth to an average

of 2.9 children, compared to the Canadian average of 1.6 children.

incidence rate of TB among Nunavut’s infants is especially worrisome given that

Nunavut has the highest

fertility rate in the country, with women giving birth to an average

of 2.9 children, compared to the Canadian average of 1.6 children.

This

means many more infants are in danger.

means many more infants are in danger.

|

|

A group

of young Inuit children play in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut in August 2013.

THE

CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick |

While

Nunavut did not report any infant deaths in 2017, the consequences of even a

successfully treated TB infection can include a host of problems, including lifelong

cognitive impairment.

Nunavut did not report any infant deaths in 2017, the consequences of even a

successfully treated TB infection can include a host of problems, including lifelong

cognitive impairment.

Since

babies exposed to TB tend to develop active disease faster than adults, infant

TB is a sign that the disease is circulating

in the community.

babies exposed to TB tend to develop active disease faster than adults, infant

TB is a sign that the disease is circulating

in the community.

The true

crux of Nunavut’s TB problem, as shown by the documents I obtained through the

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), is that poor data quality and a lack of

data showing preventative treatment measures means that nobody fully knows the

extent of the outbreak.

crux of Nunavut’s TB problem, as shown by the documents I obtained through the

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), is that poor data quality and a lack of

data showing preventative treatment measures means that nobody fully knows the

extent of the outbreak.

TB

monitoring failures

monitoring failures

I sent

ATI requests to the Ministry of Health in Nunavut, Health Canada and PHAC

asking how many people in Nunavut were offered prophylactic treatment after

being exposed to TB, how many received it and how many completed it.

ATI requests to the Ministry of Health in Nunavut, Health Canada and PHAC

asking how many people in Nunavut were offered prophylactic treatment after

being exposed to TB, how many received it and how many completed it.

Ron

Wassink, a communications specialist for the Nunavut Department of Health. said

that no statistics for prophylactic treatment are available because: “The

database is still under development and as such is not ready to create summary

statistics nor would it be appropriate to do so at this time until the database

is fully operational.”

Wassink, a communications specialist for the Nunavut Department of Health. said

that no statistics for prophylactic treatment are available because: “The

database is still under development and as such is not ready to create summary

statistics nor would it be appropriate to do so at this time until the database

is fully operational.”

|

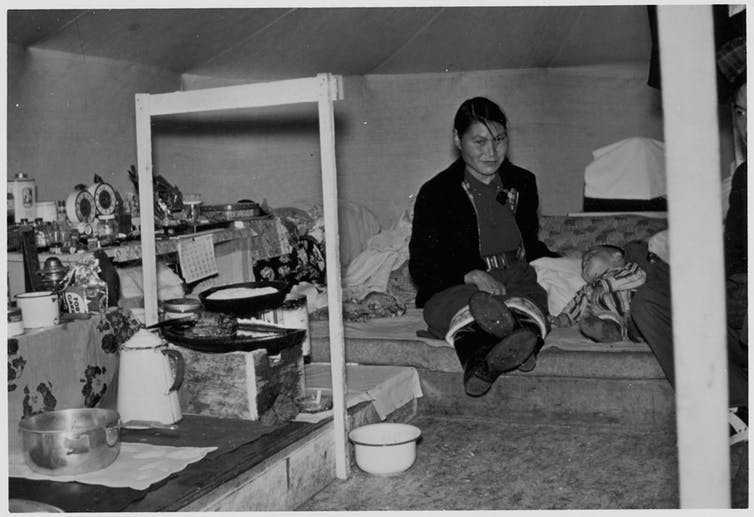

| At least one-third of Inuit were infected with TB in the 1950s. Here, an Inuit woman with active tuberculosis sits with her young son. (Health and Welfare Canada / Library and Archives Canada) |

Prophylactic

treatment can prevent people from developing latent TB, the not-yet-contagious

precursor to active TB. Knowing the number of people offered prophylactic

treatment, a treatment that is recommended by the World Health Organization but

is not mandatory, gives researchers a true grasp of the amount of disease

circulating in a community.

treatment can prevent people from developing latent TB, the not-yet-contagious

precursor to active TB. Knowing the number of people offered prophylactic

treatment, a treatment that is recommended by the World Health Organization but

is not mandatory, gives researchers a true grasp of the amount of disease

circulating in a community.

The data

that do exist about the outbreak, as shown in the PHAC report I accessed, are

frighteningly incomplete.

that do exist about the outbreak, as shown in the PHAC report I accessed, are

frighteningly incomplete.

The

report explains that each community in Nunavut should have been keeping a

separate Excel spreadsheet for active cases and contacts and importing them

into a database. However, some Nunavut communities were left out of this

process because their records were “in a format not conducive for data import.”

report explains that each community in Nunavut should have been keeping a

separate Excel spreadsheet for active cases and contacts and importing them

into a database. However, some Nunavut communities were left out of this

process because their records were “in a format not conducive for data import.”

Even now,

in 2018, there is no adequate database for TB monitoring.

in 2018, there is no adequate database for TB monitoring.

Incidence

rates out of control

rates out of control

Each

active case of TB requires contact investigation. This helps health officials

find people who are at risk of developing and spreading the disease.

active case of TB requires contact investigation. This helps health officials

find people who are at risk of developing and spreading the disease.

Contacts,

which include people living in the same house, should be offered prophylactic

treatment if they qualify for it, or they should receive follow-up monitoring

for two years to check for symptoms.

which include people living in the same house, should be offered prophylactic

treatment if they qualify for it, or they should receive follow-up monitoring

for two years to check for symptoms.

The

report shows that local health care workers failed to list the contact type in

42.4 per cent of investigations. This is assigned based on how much time the

patient spent with their family member, spouse or perhaps a friend staying in

their home.

report shows that local health care workers failed to list the contact type in

42.4 per cent of investigations. This is assigned based on how much time the

patient spent with their family member, spouse or perhaps a friend staying in

their home.

The

categorization of contact type is vital for determining whether a person should

be treated.

categorization of contact type is vital for determining whether a person should

be treated.

While the

federal government’s funding announcement and strategy are important steps in

the right direction, the PHAC report shows that the current data are of poor

quality and that the incidence rate of TB in Nunavut’s most vulnerable

population is out of control.

federal government’s funding announcement and strategy are important steps in

the right direction, the PHAC report shows that the current data are of poor

quality and that the incidence rate of TB in Nunavut’s most vulnerable

population is out of control.

With the

hiring of more staff, a more culturally sensitive program and better quality

data, it is entirely likely that the number of cases of TB detected will

actually increase before they decrease because of better detection.

hiring of more staff, a more culturally sensitive program and better quality

data, it is entirely likely that the number of cases of TB detected will

actually increase before they decrease because of better detection.

Until we

can accurately quantify the scope of the current problem, it is very difficult

to foresee an end to the current TB outbreak.

can accurately quantify the scope of the current problem, it is very difficult

to foresee an end to the current TB outbreak.