On Brink of a Stable Peace, Colombia Faces Familiar US-Backed Right-Wing Elements Seeking to Subvert It

MintPressNews, March 23rd, 2018

Colombia’s

peace agreement with the FARC has been threatened by continued violence against

social leaders and now, with elections approaching, a potential far-right

resurgence fueled by fear could trigger a return to militarism.

peace agreement with the FARC has been threatened by continued violence against

social leaders and now, with elections approaching, a potential far-right

resurgence fueled by fear could trigger a return to militarism.

|

| Colombia’s former President Alvaro Uribe listens to a question during an interview in Bogota, Colombia. Colombian authorities have detained President Uribe’s younger brother Santiagowas charged with the creation of right-wing paramilitary groups during the 1990’s. (AP/Fernando Vergara, File) |

BOGOTA,

COLOMBIA — With Colombia’s March 11 legislative elections ending in a near tie

between right- and left-wing coalitions, the future of an already precarious

peace process most likely hinges on the May 27 presidential vote.

COLOMBIA — With Colombia’s March 11 legislative elections ending in a near tie

between right- and left-wing coalitions, the future of an already precarious

peace process most likely hinges on the May 27 presidential vote.

When

far-right uribista Ivan Duque of Centro Democratico (Democratic Center) squares

off against left-leaning former Bogota mayor Gustavo Petro, it will determine

the trajectory of the close U.S. ally, and whether or not the most recent

attempt at peace might continue.

far-right uribista Ivan Duque of Centro Democratico (Democratic Center) squares

off against left-leaning former Bogota mayor Gustavo Petro, it will determine

the trajectory of the close U.S. ally, and whether or not the most recent

attempt at peace might continue.

With the

candidates nearly tied

in polls, Colombia’s future remains uncertain.

candidates nearly tied

in polls, Colombia’s future remains uncertain.

What is

certain however, is that for a century, Colombia’s oligarchy has stopped at

nothing to dismantle worker and peasant organizing. Although Colombians want

peace, is it possible in such a situation?

certain however, is that for a century, Colombia’s oligarchy has stopped at

nothing to dismantle worker and peasant organizing. Although Colombians want

peace, is it possible in such a situation?

Famously

fictionalized but eternally real in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ seminal One Hundred

Years of Solitude, the Colombian military, with the support of the United

States, massacred

thousands of United Fruit Company banana workers in 1928 for

striking.

fictionalized but eternally real in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ seminal One Hundred

Years of Solitude, the Colombian military, with the support of the United

States, massacred

thousands of United Fruit Company banana workers in 1928 for

striking.

Today,

the political dynamic is largely the same. Names and methods may have changed,

but not by much. United Fruit Company is now Chiquita, but the latter, along

with Coca-Cola and Dole, was found guilty

of funding campesino-murdering paramilitaries as recently as 2004.

Nobody served jail time.

the political dynamic is largely the same. Names and methods may have changed,

but not by much. United Fruit Company is now Chiquita, but the latter, along

with Coca-Cola and Dole, was found guilty

of funding campesino-murdering paramilitaries as recently as 2004.

Nobody served jail time.

The deep

roots of violence and class war in Colombia

roots of violence and class war in Colombia

|

| A street car is overturned and burned during an uprising following the assassination of Jorge Eliecer Gaitan in Bogota, Columbia. The 1948 assassination of Gaitan sparked the political bloodletting known as “La Violencia,” or “The Violence.” (AP/E. L. Almen) |

Colombia’s

2016 peace agreement, for which outgoing center-right President Juan Manuel

Santos won a Nobel Prize, has been widely praised internationally. As a result

of the deal, Latin America’s oldest leftist guerrilla organization, the former

Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), is now a legal electoral party,

the Revolutionary Alternative Forces of the Commons (also FARC).

But has

this peace truly managed to transform the roots of the country’s violence?

Since the FARC’s demobilization, hundreds of social leaders, including trade

unionists, campesino leaders, and coca farmers have been brutally

murdered. Demobilized FARC members have also been targeted, with around 56

people affiliated with the former guerrilla organization turned political party

having been killed since so-called “peace.”

this peace truly managed to transform the roots of the country’s violence?

Since the FARC’s demobilization, hundreds of social leaders, including trade

unionists, campesino leaders, and coca farmers have been brutally

murdered. Demobilized FARC members have also been targeted, with around 56

people affiliated with the former guerrilla organization turned political party

having been killed since so-called “peace.”

Paramilitary

violence in Colombia has deep roots. To learn more, MintPress spoke with

Professor Oliver Villar, author of Cocaine, Death Squads, and the War on

Terror: U.S. Imperialism and Class Struggle in Colombia, published by

Monthly Review Press.

violence in Colombia has deep roots. To learn more, MintPress spoke with

Professor Oliver Villar, author of Cocaine, Death Squads, and the War on

Terror: U.S. Imperialism and Class Struggle in Colombia, published by

Monthly Review Press.

Asked

about the origins of paramilitary violence in Colombia, Villar explained:

about the origins of paramilitary violence in Colombia, Villar explained:

Paramilitary

violence against leftists is part of Colombia’s long and deep history of class

warfare. We can go back to the Wars of Independence against Spain, but the

modern structures of paramilitary terror are traceable to La Violencia

(1948-58), when Conservatives set up death squads to assassinate their

political opponents the Liberals, as well as Communists who took up arms

against the State.”

It was this

context that led to numerous groups consisting of peasants, workers, students

and intellectuals — inspired to varying degrees by Marxism, the successful

Cuban revolution, and liberation theology — taking up arms against state and

paramilitary forces. Villar tells us:

context that led to numerous groups consisting of peasants, workers, students

and intellectuals — inspired to varying degrees by Marxism, the successful

Cuban revolution, and liberation theology — taking up arms against state and

paramilitary forces. Villar tells us:

This

violent history produced one of the most reactionary ruling classes in Latin

America but also one of the most effective and enduring forms of resistance

since the mid-20th century. As a result of this class war, was the creation of

a number of Marxist insurgencies throughout the 1960s; the most formidable were

the FARC-EP and ELN [National Liberation Army]. For over half a century, this

insurgency has existed in a virtual parallel universe, surviving the Cold War

and surviving the so-called ‘War on Terror.’”

Colombia’s

state was not acting without foreign support. As a resource-rich,

geopolitically strategic country, the United States has long seen the

“security” of Colombia as key to its own interests. Villar argues that the U.S.

has long been the “main sponsor” of state violence:

state was not acting without foreign support. As a resource-rich,

geopolitically strategic country, the United States has long seen the

“security” of Colombia as key to its own interests. Villar argues that the U.S.

has long been the “main sponsor” of state violence:

Since the

Kennedy administration identified the insurgency as being a greater threat than

the Vietcong, the U.S. has funded, trained and supported the Colombian State in

its war against leftists. In 2000, President Clinton introduced ‘Plan

Colombia,’ which was promoted as a ‘war on drugs’ but was in fact a

counterinsurgency program to eliminate the largest militant left-wing force –

the FARC.”

Plan Colombia

— implemented by the Clinton administration, but largely executed under the

Bush administration through the cooperation of far-right former Colombian

president, Alvaro Uribe Velez, who founded the Centro Democratico party — saw

over $10 billion flow into the South American nation.

— implemented by the Clinton administration, but largely executed under the

Bush administration through the cooperation of far-right former Colombian

president, Alvaro Uribe Velez, who founded the Centro Democratico party — saw

over $10 billion flow into the South American nation.

It is

often claimed by observers that

Colombia never experienced the periods of military dictatorship that swept

Latin America in the 1970s and 80s, but Villar strongly disagrees:

often claimed by observers that

Colombia never experienced the periods of military dictatorship that swept

Latin America in the 1970s and 80s, but Villar strongly disagrees:

Ex-president

Alvaro Uribe Velez is up there with America’s hard hitters: Videla, Pinochet,

Fujimori and so on.”

Alvaro Uribe Velez is up there with America’s hard hitters: Videla, Pinochet,

Fujimori and so on.”

This

hasn’t stopped Uribe from remaining one of the most influential and well-connected

Colombian politicians internationally. To this day, he regularly travels to the

U.S. for speaking

engagements at elite universities, and is praised by his friends in

the North for his supposed “success” in the “war on drugs.”

hasn’t stopped Uribe from remaining one of the most influential and well-connected

Colombian politicians internationally. To this day, he regularly travels to the

U.S. for speaking

engagements at elite universities, and is praised by his friends in

the North for his supposed “success” in the “war on drugs.”

Bolstered

by U.S.-derived money, Uribe’s terms in office oversaw a dramatic rise in

assassinations carried out by state forces. The United Nations even

acknowledges that, during his two terms, thousands were murdered by

military and police, with the crimes often covered up by disguising bodies as

FARC combatants, or blaming the killings on drug traffickers or guerrillas.

by U.S.-derived money, Uribe’s terms in office oversaw a dramatic rise in

assassinations carried out by state forces. The United Nations even

acknowledges that, during his two terms, thousands were murdered by

military and police, with the crimes often covered up by disguising bodies as

FARC combatants, or blaming the killings on drug traffickers or guerrillas.

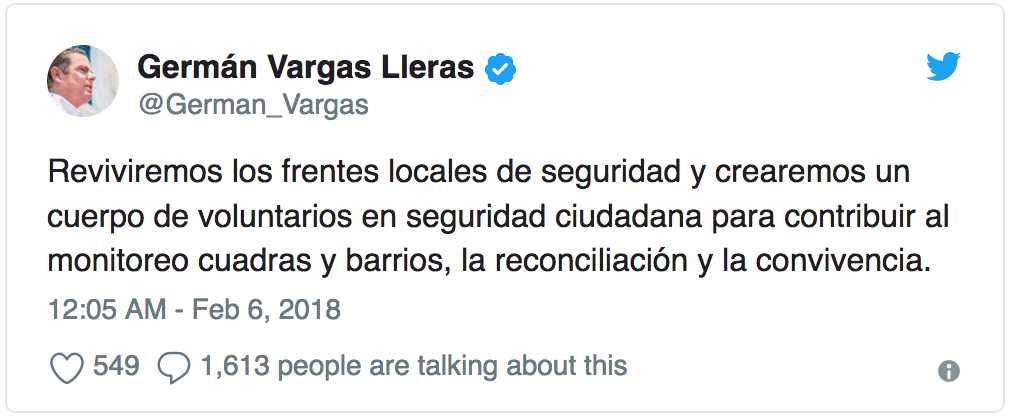

WikiLeaks

documents have demonstrated a clear connection of Uribe’s “citizen

informant” and “convivir” security programs with illegal paramilitary groups.

Right-wing politician German Vargas Lleras recently claimed in a

Tweet that these programs should be revived.

documents have demonstrated a clear connection of Uribe’s “citizen

informant” and “convivir” security programs with illegal paramilitary groups.

Right-wing politician German Vargas Lleras recently claimed in a

Tweet that these programs should be revived.

Translation

| We will revive the local security fronts and create a body of volunteers

in citizen security to contribute to the monitoring of blocks and

neighborhoods, reconciliation and coexistence.

| We will revive the local security fronts and create a body of volunteers

in citizen security to contribute to the monitoring of blocks and

neighborhoods, reconciliation and coexistence.

Uribe and

his family have faced and continue to face numerous investigations into paramilitary

ties, with accusations brought forward by left-leaning politicians

Gustavo Petro and Ivan Cepeda. In February, a court in Medellin ordered an

investigation into Uribe for his alleged role in paramilitary massacres as long

ago as the 1990s. Shortly after, Colombia’s Supreme Court called a further

investigation on suspicion that Uribe had falsified evidence and manipulated

witnesses in the cases against him.

his family have faced and continue to face numerous investigations into paramilitary

ties, with accusations brought forward by left-leaning politicians

Gustavo Petro and Ivan Cepeda. In February, a court in Medellin ordered an

investigation into Uribe for his alleged role in paramilitary massacres as long

ago as the 1990s. Shortly after, Colombia’s Supreme Court called a further

investigation on suspicion that Uribe had falsified evidence and manipulated

witnesses in the cases against him.

A

precarious “peace”

precarious “peace”

|

| A man places flowers on the grave of slain rebel leader Jorge Briceno, known as Mono Jojoy, during an homage of former members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, FARC, at a cemetery in southern Bogota, Colombia, Sept. 22, 2017. Briceno was killed by the Colombian Army on Sep. 22, 2010. (AP/Ricardo Mazalan) |

While the

FARC has held up its end of the peace deal, having successfully handed over

its weapons to the United Nations last year and registered as a

legal political party, ongoing violence shows that the social conditions that

cultivated armed struggle are still very much in place.

FARC has held up its end of the peace deal, having successfully handed over

its weapons to the United Nations last year and registered as a

legal political party, ongoing violence shows that the social conditions that

cultivated armed struggle are still very much in place.

Although

the state claims paramilitaries have demobilized, the “armed groups” continuing

to operate consist of largely the same actors as always, hailing from criminal

drug and illegal mining sectors. Gimena Sanchez — the Andes director at

Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), who tracks U.S. policy in Colombia —

told MintPress News:

the state claims paramilitaries have demobilized, the “armed groups” continuing

to operate consist of largely the same actors as always, hailing from criminal

drug and illegal mining sectors. Gimena Sanchez — the Andes director at

Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), who tracks U.S. policy in Colombia —

told MintPress News:

The

Colombian government tries to say it’s organized crime, then they called them

illegal armed groups … that tries to depoliticize their role. The reason that

Colombia doesn’t want them to be called paramilitaries is because that implies

collusion with the state.”

Sanchez,

who has spent time in the Choco region of Colombia, described how she had

observed how one of Colombia’s most notorious paramilitary groups of the Uribe

years, the United

Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC — now-demobilized), evolved

from its “pre-incarnations,” through its eventual demobilization and

disintegration into various other “criminal groups.”

who has spent time in the Choco region of Colombia, described how she had

observed how one of Colombia’s most notorious paramilitary groups of the Uribe

years, the United

Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC — now-demobilized), evolved

from its “pre-incarnations,” through its eventual demobilization and

disintegration into various other “criminal groups.”

“I can

say in that region (Choco), the names have changed, but they are the same

people,” Sanchez said.

say in that region (Choco), the names have changed, but they are the same

people,” Sanchez said.

Peace

with guerrillas had been tried before in Colombia, and ended in tragedy. When

the FARC’s previous electoral project, Marcha Patriótica, enjoyed significant

electoral success in 1986 with a land-reform platform, it provoked the ire of

Colombia’s landed interests and criminal networks. In the 1980s and 1990s,

paramilitaries massacred

thousands of Marcha Patriótica members, destroying the party and

reigniting war. The party wasn’t able to reconstitute as an entity distinct

from the FARC until 2013, a ghost of what it could have been, haunting all

subsequent efforts at peace.

with guerrillas had been tried before in Colombia, and ended in tragedy. When

the FARC’s previous electoral project, Marcha Patriótica, enjoyed significant

electoral success in 1986 with a land-reform platform, it provoked the ire of

Colombia’s landed interests and criminal networks. In the 1980s and 1990s,

paramilitaries massacred

thousands of Marcha Patriótica members, destroying the party and

reigniting war. The party wasn’t able to reconstitute as an entity distinct

from the FARC until 2013, a ghost of what it could have been, haunting all

subsequent efforts at peace.

Trading

guns for roses

guns for roses

|

| Ivan Marquez holds a red rose, the symbol of the new political party Alternative Communal Revolutionary Forces, during a press conference in Bogota, Colombia, Sept. 1, 2017. (AP/Fernando Vergara) |

The

electoral road has not been easy for the FARC this time around. As an electoral

party with a new “rose” logo, they failed to win any more than the 10

legislative seats they were already guaranteed in the peace agreement. Ongoing

health problems, as well as near constant threats of violence, forced FARC

leader, Rodrigo “Timochenko” Londoño, to withdraw his

presidential campaign.

electoral road has not been easy for the FARC this time around. As an electoral

party with a new “rose” logo, they failed to win any more than the 10

legislative seats they were already guaranteed in the peace agreement. Ongoing

health problems, as well as near constant threats of violence, forced FARC

leader, Rodrigo “Timochenko” Londoño, to withdraw his

presidential campaign.

But while

mainstream media claim that the FARC’s difficulties as a legal party are a

“rejection” of the former guerrillas by the Colombian people, the FARC’s

leaders say that the lack of guarantees promised them in the peace deal has

made their electoral efforts to reach the Colombian people difficult to

impossible.

mainstream media claim that the FARC’s difficulties as a legal party are a

“rejection” of the former guerrillas by the Colombian people, the FARC’s

leaders say that the lack of guarantees promised them in the peace deal has

made their electoral efforts to reach the Colombian people difficult to

impossible.

Londoño

wrote in a March blog post:

wrote in a March blog post:

The party

of the commons won in spite of the obstacles and impediments, in spite of the

propaganda war, and very much in spite of the deaths among us, because we have

persisted in the political space won during decades of heroic struggle.”

International

and national opinion recognizes the threats, aggressions, and violent actions

organized against our candidates by representatives of the Centro Democratico.

No heart but mine resisted the suspension of our campaign more, with the

consequences it would have. But without the support of the State, without

electoral machines, without clientelism, without money, without corruption,

with the ‘media of mass destruction’ against us, facing dirty campaigns, but

armed with love, honesty, and conviction, of course we are victors.”

The FARC

— attempting to combat a negative perception among some in the cities

cultivated by years of media coverage portraying them as terrorists — have been

met with protests at their campaign rallies, which they say are provoked by

right-wing uribista groups.

— attempting to combat a negative perception among some in the cities

cultivated by years of media coverage portraying them as terrorists — have been

met with protests at their campaign rallies, which they say are provoked by

right-wing uribista groups.

Following

the legislative elections on March 11, the FARC released a

statement denouncing the fact that they were prohibited from opening

a bank account to access the campaign money to which they were legally

entitled.

the legislative elections on March 11, the FARC released a

statement denouncing the fact that they were prohibited from opening

a bank account to access the campaign money to which they were legally

entitled.

Reports of

vote fraud also emerged, something that has been claimed by many

political actors and observers.

vote fraud also emerged, something that has been claimed by many

political actors and observers.

Still,

the FARC is optimistic, and has said that “in spite of great difficulties

faced,” they will use their 10 senate seats to forge alliances with progressive

forces, secure the peace agreement, and work toward reforming an outdated and

broken electoral system. Newly elected FARC senator Pablo Catatumbo tweeted:

the FARC is optimistic, and has said that “in spite of great difficulties

faced,” they will use their 10 senate seats to forge alliances with progressive

forces, secure the peace agreement, and work toward reforming an outdated and

broken electoral system. Newly elected FARC senator Pablo Catatumbo tweeted:

Translation

| Our parliamentary action will focus on the pending reforms for the

implementation of the Peace Agreement and on legislative projects that improve

the living conditions of the majorities.

| Our parliamentary action will focus on the pending reforms for the

implementation of the Peace Agreement and on legislative projects that improve

the living conditions of the majorities.

Most

significantly however, the FARC has

assured that their project will not limit itself to the electoral

realm:

significantly however, the FARC has

assured that their project will not limit itself to the electoral

realm:

With the

understanding that we don’t exclusively define ourselves as an electoral party,

we express our desire and firm intention to be with the social and popular

struggles in all parts of our country; we will be present in just causes of

protest, and the mobilization of the people of the common, and support the

dynamic constituents that generate social and popular movements.”

In spite

of their optimism, the withdrawal of Londoño from the campaign and their

difficulties in finding their footing electorally without the proper guarantees

from the State represent another major threat to the precarious peace. Many

observers argue that the ball is in the Santos government’s court to ensure

that their peace project doesn’t dissolve through a loss of trust.

of their optimism, the withdrawal of Londoño from the campaign and their

difficulties in finding their footing electorally without the proper guarantees

from the State represent another major threat to the precarious peace. Many

observers argue that the ball is in the Santos government’s court to ensure

that their peace project doesn’t dissolve through a loss of trust.

WOLA’s

Sanchez told MintPress:

Sanchez told MintPress:

If it

(the government) doesn’t implement the provisions related to land, truth,

justice and political plurality, as well as the programs designated for the

coca farmers, it won’t be too long before new armed groups confront the state.”

Uribe’s

return?

return?

|

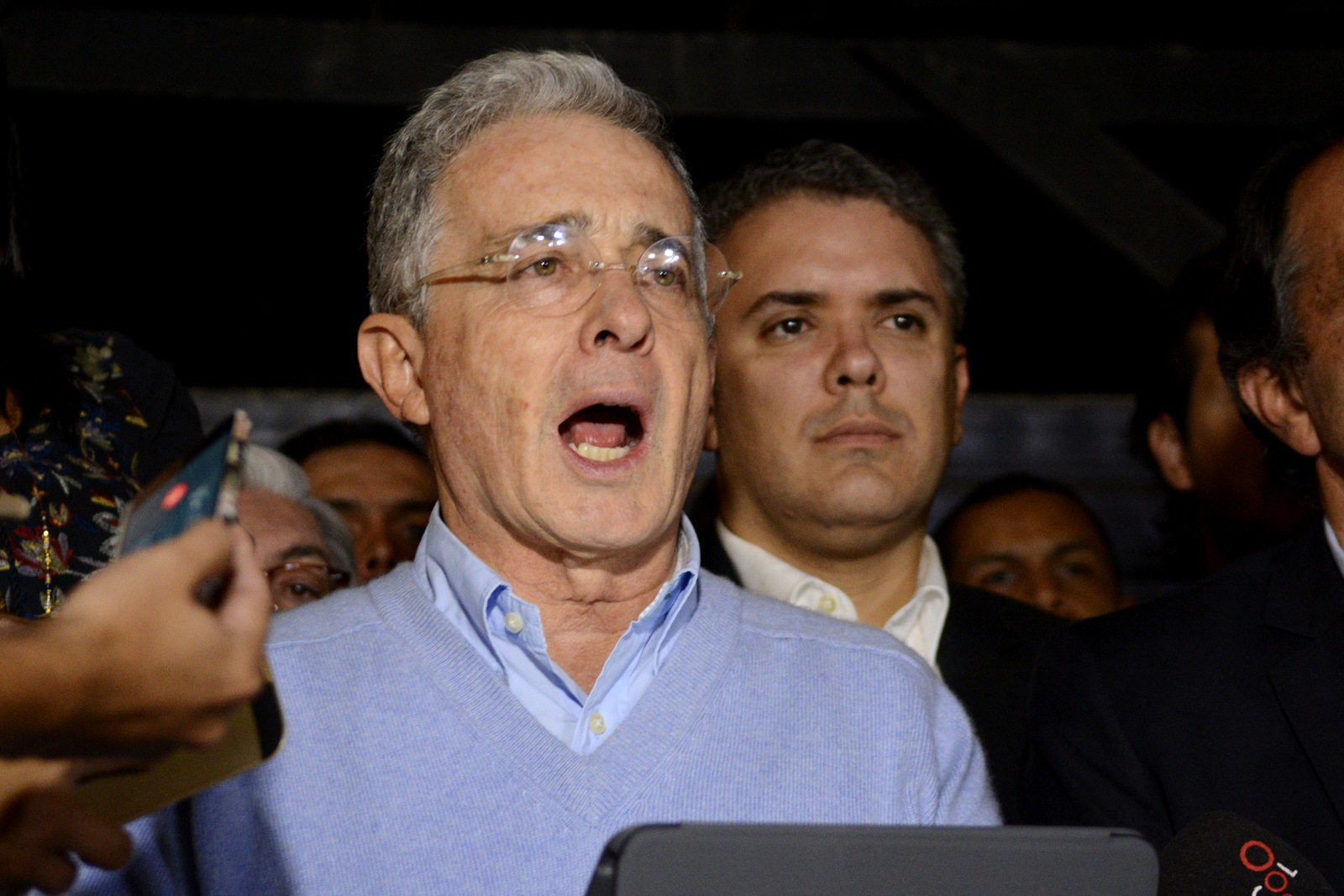

| Former President Alvaro Uribe, flanked by presidential candidate Ivan Duque, reads a statement at his house in Rionegro, Colombia, Oct. 2, 2016. (AP/Luis Benavides) |

When Juan

Manuel Santos, a former defense minister under Uribe, took the presidency, it

split Colombia’s oligarchy in two between those who wanted to try for peace

with the FARC, and those who, in Villar’s words, want to “finish what they

started.”

Manuel Santos, a former defense minister under Uribe, took the presidency, it

split Colombia’s oligarchy in two between those who wanted to try for peace

with the FARC, and those who, in Villar’s words, want to “finish what they

started.”

The uribista

camp has remained a strong political force, opposing a

peace deal from the beginning, while Santos and his allies who

ranged across the political spectrum negotiated the eventual disarmament of the

FARC in exchange for immunity and legal political participation.

camp has remained a strong political force, opposing a

peace deal from the beginning, while Santos and his allies who

ranged across the political spectrum negotiated the eventual disarmament of the

FARC in exchange for immunity and legal political participation.

Under the

Obama administration, the U.S. Congress promoted the peace agreement under

bipartisan consensus, and renamed the Plan Colombia program “Paz Colombia.”

Obama administration, the U.S. Congress promoted the peace agreement under

bipartisan consensus, and renamed the Plan Colombia program “Paz Colombia.”

Villar

argues:

argues:

The

government of Juan Manuel Santos represents the modern bourgeoisie, the agro-mineral

and financial classes, urban and cosmopolitan, closely intertwined with the

interest of U.S. finance capital, which was strongly supported by Obama. Uribe

and the “extreme right” represent the narcobourgeoisie who fought the war with

paramilitary death squads.”

The

extreme-right “narcobourgeoisie” forces behind Uribe could see a return in May

27 elections, should the Centro Democratico’s candidate, Ivan Duque, assume the

presidency.

extreme-right “narcobourgeoisie” forces behind Uribe could see a return in May

27 elections, should the Centro Democratico’s candidate, Ivan Duque, assume the

presidency.

Camilo

Gonzalez, the director of the Institute for Studies of Development and Peace

(Indepaz), said in a statement

recently:

Gonzalez, the director of the Institute for Studies of Development and Peace

(Indepaz), said in a statement

recently:

With the

tie in the composition of the Congress of the Republic, the fate of the peace

accord implementation depends on the results of the presidential elections.”

Presidential

candidate Ivan Duque, who is neck and neck with Gustavo Petro, has opposed the

peace process every step of the way, and refuses to acknowledge the

FARC as a legitimate political party, saying he “doesn’t like giving prizes to

criminals.”

candidate Ivan Duque, who is neck and neck with Gustavo Petro, has opposed the

peace process every step of the way, and refuses to acknowledge the

FARC as a legitimate political party, saying he “doesn’t like giving prizes to

criminals.”

In an interview

with Colombian paper El Pais, Duque said:

with Colombian paper El Pais, Duque said:

There are

legal issues involving the impunity in this country for FARC criminals; our

agenda includes dealing with criminal drug gangs, with the rise in illicit

crops, and with the ELN guerrilla. For that, the state will need a great

capacity for offensive and deterrence action.”

A return

to uribismo could also be reflective of a shift in the United States’ attitude

under the Trump administration toward one that desires a yet more militarized

Colombia to regionally counter Venezuela.

to uribismo could also be reflective of a shift in the United States’ attitude

under the Trump administration toward one that desires a yet more militarized

Colombia to regionally counter Venezuela.

According

to WOLA’s Sanchez, although the U.S. Senate is still largely supportive of

peace and the Santos approach, the Trump administration has focused on two

things: the drug war, and Colombia’s socialist neighbor Venezuela. Trump may be

taking more cues from Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL), who is close with Uribe.

to WOLA’s Sanchez, although the U.S. Senate is still largely supportive of

peace and the Santos approach, the Trump administration has focused on two

things: the drug war, and Colombia’s socialist neighbor Venezuela. Trump may be

taking more cues from Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL), who is close with Uribe.

Rubio has

recently been highly critical of Trump’s pick for Colombian ambassador, Joseph

Macmanus — pushing for someone more hardline, who could enforce “America First”

in Colombia — and criticized him during a Senate confirmation

hearing on March 7. It remains unclear whether or not, at Rubio’s

urging, Macmanus will join the ranks of the fired in Trump’s administration.

Sanchez concluded:

recently been highly critical of Trump’s pick for Colombian ambassador, Joseph

Macmanus — pushing for someone more hardline, who could enforce “America First”

in Colombia — and criticized him during a Senate confirmation

hearing on March 7. It remains unclear whether or not, at Rubio’s

urging, Macmanus will join the ranks of the fired in Trump’s administration.

Sanchez concluded:

Marco

Rubio said in the hearing we have to protect Colombia from the threat of

Venezuela. I think we’ll be hearing a lot more of this, that Colombia is a

barrier for Venezuela. If history repeats itself, with another Uribe, you could

see more tensions.”

Colombia

regional positioning makes it geopolitically an important piece in the “America

First” agenda. Villar argues:

regional positioning makes it geopolitically an important piece in the “America

First” agenda. Villar argues:

Donald

Trump has declared that the United States is facing growing competition from

Russia and China, two great-power rivals which he says ‘seek to challenge U.S.

influence, values and wealth.’ The Colombian question is vital to U.S.

domination and, as Trump knows, ‘America is in the game,’ one that he thinks

‘America is going to win.’ But so is America’s main competitor in the region,

China.”

With a

campaign built on fear-mongering, that “castrochavismo,”

an amalgam of Cuban and Venezuelan revolutionary leaders Fidel Castro and Hugo

Chavez, will “destroy” Colombia, and a population apathetic toward the

country’s politics (over 62 percent of Colombians abstained in

2016’s referendum on peace), Duque stands a chance at winning,

putting the Santos peace deal at risk.

campaign built on fear-mongering, that “castrochavismo,”

an amalgam of Cuban and Venezuelan revolutionary leaders Fidel Castro and Hugo

Chavez, will “destroy” Colombia, and a population apathetic toward the

country’s politics (over 62 percent of Colombians abstained in

2016’s referendum on peace), Duque stands a chance at winning,

putting the Santos peace deal at risk.

Perhaps

only one thing is certain in Colombian politics at the moment: for Colombia’s

poorest, peace is likely to remain only a fantasy of the wealthy while an

entrenched oligarchy continues dismantling progressive aspirations, physically

and ideologically, one century after those same reactionary forces massacred

thousands so that those in the North could eat their cheap bananas.

only one thing is certain in Colombian politics at the moment: for Colombia’s

poorest, peace is likely to remain only a fantasy of the wealthy while an

entrenched oligarchy continues dismantling progressive aspirations, physically

and ideologically, one century after those same reactionary forces massacred

thousands so that those in the North could eat their cheap bananas.