From Belfast to Guantánamo: the Alleged Torture of Northern Ireland’s “Hooded Men”

Summer Eldemire, The intercept,

March 22 2018

Auld, it began at a house party.

|

|

Five of

the “Hooded Men,” who were kept in hoods interned in Northern Ireland in 1971. Francie McGuigan, center, with, from left, Patrick McNally, Liam Shannon, Davy Rodgers, and Brian Turley, pictured in Belfast after the European Court of Human Rights delivered its judgment on their treatment on Tuesday, March 20, 2018. |

On August

9, 1971, while he and his friends drank pints of beer and danced to the Rolling

Stones in their nationalist neighborhood of West Belfast, the government of

Northern Ireland and the British Army launched “Operation Demetrius.” Auld

strolled back to his parents’ house around 3:30 a.m. and thought it was odd

that the lights were still on. He found the door already open, and a man with a

rifle waiting for him on the other side. Soldiers jumped out from the bushes

and shoved him inside.

memory of that evening remains sharp because of what followed: He and 13 other

Irish Catholics were subjected to treatment that on Tuesday the European Court

of Human Rights declared

“inhumane and degrading,” but rejected to revise as legally torture. The

government took the men to a secret detention facility and used them as guinea

pigs to perfect what would later be called the “Five Techniques.” The court had

originally ruled in 1978 that the treatment was not severe or cruel enough to

be classified as torture.

the Irish government appealed to have the case revised after an investigation

uncovered that high cabinet British government officials had authorized the

detainment and hid evidence from the court showing the treatment’s long-lasting

effects. An all-star legal team, including Amal Clooney, represented the men.

the British government banned the use of the Five Techniques in 1972, the

country’s military would go on to use them until at least 2003, when they

resulted in the death

of Baha Mousa, an Iraqi civilian detainee. The U.S. also adopted and fine-tuned

the same methods for use after the September 11, 2001 attacks. The Bush

administration cited the European court’s 1978 verdict in defense of its

so-called enhanced interrogation techniques during the war on terror.

Similarly, the Israeli government used the verdict to defend itself against

accusations of torturing Palestinian detainees. The fate of the 14 Irishmen –

who became known as the “Hooded Men” because their heads were hooded through

their interrogations – had international ramifications.

the men – Sean McKenna, Michael Montgomery, Patrick Shivers, and Gerry McKerr –

are not alive to see the latest ruling in the case. But it was a disappointing

day for the 10 surviving members of the group – Jim Auld, Kevin Hannaway,

Francis McGuigan, Patrick J. McClean, Michael J. Donnelly, Davy Rodgers, Liam

Shannon, Patrick McNally, Brian Turley, and Joseph Clarke – who had hoped that

the court would declare they were tortured.

executive director of Amnesty International Ireland, Colm O’Gorman, described

the ruling as “regrettable.” The judges focused on a narrow legal technicality,

he said, rather than addressing the substance of the torture claims. Because

the case was a request to revise an earlier judgment and not a fresh case, the

court debated whether the new evidence would have impacted the original 1978

decision, not what it would mean in today’s society. “We are quite confident

what was done to these men would be deemed as torture by the court in today’s

terms if this case were heard afresh,“ said O’Gorman.

Teggart, Amnesty’s Northern Ireland campaign manager, said the court had

“missed a vital opportunity to put right a historic wrong.“ She added: “The

‘Hooded Men’ have been denied justice for too long.“

one final option for the men in the European Court of Human Rights. They could

request that the case be submitted to the court’s Grand Chamber. Case

coordinator Jim McIlmurray, who brought the men together in 2011 for the first

time in 40 years, said they were ready to go on to the next step and would be

pursuing all avenues. The group is also pursuing a case through the court of

appeals in Belfast for an independent inquiry into the events of 1971.

|

| Jim Auld pictured at his home in Belfast on March 15, 2018. Photo: Rebecca Blandón |

As a

teenager, Auld had split his time between chasing girls and demonstrating in

the marches of the civil rights movement, as the minority Catholic group in

Northern Ireland fought back against discrimination. It was one of those

protests that, in October 1968, ended in riots – and sparked the 30-year

conflict known as the “Troubles.”

Ireland is at the tip of Ireland, occupying about one-sixth of its landmass.

When its southern neighbor broke away from England in 1922, Northern Ireland

stayed under British governance. Afterward, the region became fiercely divided

between Protestant unionists who supported staying under British rule and

minority Catholic nationalists, like Auld and his family, who felt they

belonged to the Irish Republic.

remembers the Troubles percolating in the months beforehand. Every night, the

television had shown police suppressing rioters. But it all felt distant until

the moment he says he saw armed Protestant paramilitary gangs, which

sometimes included police and military, charging into his neighborhood and

burning down houses. During riots in 1969, many houses — mostly Catholic — were

burned, and thousands of Catholics were forced out of their homes.

for an interview with The Intercept and recounted his memories in detail. The

European Court of Human Rights has acknowledged Auld’s testimony and the

government of Northern Ireland has not denied his version of events. The

Northern Ireland office of the U.K. government did not respond to Auld’s

allegations, but a spokesperson stated, “We continue to condemn unreservedly

the use of torture or inhumane treatment.”

authorities arrested Auld on August 9, 1971, he says he immediately started

taking his jacket off, so his parents could bear witness that he had no bruises

before the soldiers arrested him. The authorities were looking for anyone

suspected of association with the Irish Republican Army, better known as the

IRA, a paramilitary group proscribed as a terrorist organization in

the U.S. and the U.K. In response to escalating violence, the government

passed a law enabling authorities to indefinitely detain suspected terrorists

without trial.

a British military captain assured him, “While you’re with me Mr. Auld, I

guarantee nothing will happen.” The soldiers loaded him into the back of a

truck and took him to a local detention center. When they offloaded him, he

says the captain told him, “You’re no longer under my custody,” and a guard hit

Auld over the back of the head with a rifle butt.

government detained about 350 men, mostly Catholics, between August 9 and 10,

but selected Auld as one of only 14 for “deep interrogation” in a secret

facility in Ballykelly, a lonesome village in the far north of the country.

Before being taken away, Auld glimpsed his friends Kevin Hannaway, Francis

McGuigan, and Joe Clarke. He says one of the soldiers gave him a cigarette and

told him, “Here, you poor bastard. You’re going to need that.” That’s when he

realized that things were serious. The guards placed a hood over his head.

“A human

being looked at me and approved me to be tortured.”

of weeks before his arrest, Auld had picked up a Newsweek magazine at the

dentist’s office. A picture of an American helicopter in Vietnam stretched

across two pages and “circled in the middle was a figure that had just been

thrown out … to be killed,” said Auld. This is what he thought of when he heard

the sound of a helicopter and the guards loaded him onto it. The next thing

he’d felt was a boot on his back. He didn’t have time to see his life flash

before his eyes; he landed about 6 feet below, the helicopter had been

hovering just off the ground.

arrived at the Ballykelly facility, a doctor had examined Auld and ruled him

fit for interrogation. To this day, Auld is still in disbelief. “A human being

looked at me and approved me to be tortured.” Part of Tuesday’s appeal hinged

on documentation that a doctor had misled the court by saying that the effects

of the ill treatment were short-lived, all the while knowing their long-lasting

impact. The court did not find this evidence convincing. They ruled that even

if the doctor had provided misleading evidence, it could not be said that that

would have influenced a finding of torture. They concluded that there was

simply not enough scientific evidence at that time.

Techniques are wall standing (the stress position), hooding, subjection to

noise, deprivation of sleep, and deprivation of food and drink. The guards had

placed Auld standing with his hands against the wall with his fingers spread.

When he moved, they beat him. When he fell, they lifted him and put him back

against the wall. After a while, he didn’t mind the beatings, as they “were

allowing your blood to circulate and giving you a relief from that heavy

numbness,” he said. This went on for at least seven days and nights.

guards had removed the hood only once during his detainment. A bright light was

shined into his eyes, and a voice repeatedly asked, “Who do you know in the

IRA?” Auld had said he didn’t know anyone. “It was like something out of a

movie,” he recalled. He told them names of two famous republican paramilitary

leaders who had appeared regularly on the television. “Trust me, if I had known

anyone, I would have told them,” he said.

clear why Auld had been selected out of the 350 men initially rounded up.

It is possible that geography played a factor. At first, there were only 12 men

taken in for interrogation, four from each of the three provinces, according

to the 1974 book called “The Guineapigs.” Questioned about whether he had

any obvious links to the IRA, Auld responds that even if he had, no human

should have been treated the way he was. The government never charged him with

a crime.

passed in and out of consciousness. He had hallucinated. He had no access to a

toilet. They fed him only once, but his mouth was too dry to eat, having not

drunk water for three days. In the background, there had been a constant

noise that he thought would drive him mad.

didn’t think the government would possibly allow him out alive. During one of

the 10 or 15 times he remembers collapsing during his interrogations, he

identified a heating pipe running along the bottom of the wall. He had tried to

throw his head against it to kill himself. When he would regain consciousness,

he bawled upon realizing that his worst nightmare had come true: He

was still alive.

guards released Auld from Ballykelly, they had detained him in prison for nine

months before admitting him to a mental hospital for “blackouts,” a likely

symptom of post-traumatic stress. “I’d start thinking about what happened and

my brain would just shut off,” said Auld. After a few weeks, he realized he

could check himself out. He says he signed the papers, walked out the door, and

took the bus home to his astonished family.

a difficult time adjusting back to life afterward. He couldn’t settle in a job.

He went back to a mental hospital. Auld had received a payment of about £16,000

($22,600) after a settlement in the courts in Belfast. He bought a blue sports

car. He found satisfaction working in conflict resolution with youth who had

experienced violence because he felt he had “an empathy.”

idea that the government of Ireland, in 1976, had taken a case to the European

Commision of Human Rights. He says no one had consulted him. Ireland initially

won the case. But two years later, the government of Northern Ireland appealed

it in a higher court, which reversed the ruling.

|

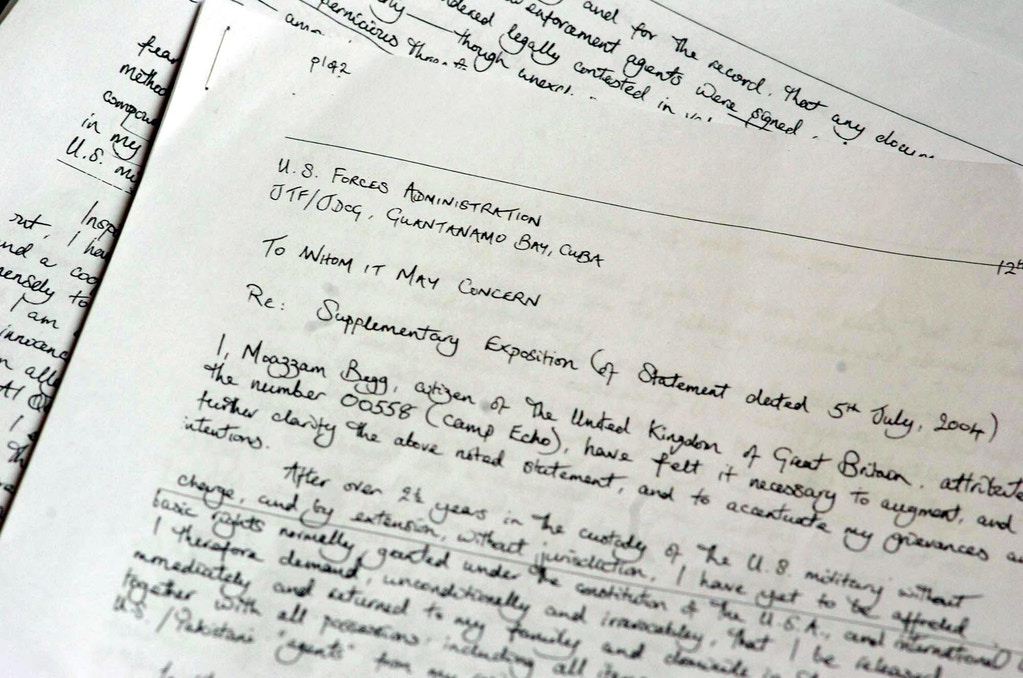

| A photocopy of a letter from British Guantánamo Bay detainee Moazzam Begg, shown during a press conference in central London in 2004. Photo: Johnny Green/AP |

realized that others had experienced the Five Techniques some 25 years later,

when he heard a talk by Moazzam Begg, a former Guantánamo detainee and outreach

director of Cage, a London-based

organization that campaigns against abuses of counterterrorism powers. Auld

says that he and Begg discussed their respective experiences. Auld had not been

able to speak to anyone before about his ordeal because, as he puts it, “It’s

not great dinner conversation.”

angry when he realized that even though the British government had banned the

techniques in 1972, Begg endured similar treatment while he was at Guantánamo.

This was proof to Auld that the brutal British methods had been exported and

expanded upon.

until 2014 that new evidence would come to light. Documents uncovered by

Irish broadcaster RTE revealed that the British government lied to

the European Court of Human Rights about the severity of the techniques and the

long-term physical and psychological consequences for the victims. The

documents also revealed that the Secretary of Defense, Peter Carrington, had

authorized the interrogation tactics, and that Prime Minister James Callaghan

knew about it.

showing the involvement of ministers in high positions formed a key part of

Ireland’s request to reopen the case. But on Tuesday, the court ruled that the

documents demonstrated nothing new. The court said the original 1978 hearing

had been well aware that the harsh methods had been signed off at a high

level.

ruling was delivered amid a newly reignited debate in the U.S. around the use

of torture, after the Trump administration announced Gina Haspel would be the

new head of the CIA. Haspel previously oversaw

a secret prison in Thailand, where the agency’s officers had used torture

methods such as waterboarding, according to a declassified

report published in 2014. The extent of Haspel’s involvement in the

abusive techniques is not yet known. She will have to have to answer questions

about her role during her Senate confirmation.

that if the court had revised the ruling, it could have set a precedent,

establishing that any use of the Five Techniques after 1978 amounted to

torture. He felt that the judges overseeing the case did not want to deal with

the immense implications that a revision may have caused. He was remarkably

cheery after hearing the news and ready to pursue the case as long as it took

to get justice.

lives in a quiet part of Belfast. He works part-time with a conflict resolution

organization, dissuading paramilitaries like the IRA from using violence in

their informal justice systems. Days before the court’s decision, Auld

says he traveled to the city of Derry to dissuade someone from delivering a

“kneecapping,” the trademark paramilitary punishment of shooting someone in the

knee. On the weekends, he takes his peregrine falcon to the woods to hunt and

find some kind of peace.