When homosexuality was an “illness,” this bisexual boxer knocked out his homophobic opponent — and killed him

|

| Laura Smith – Jan 28, 2018 |

It should have been a great fight. In March of 1962, welterweights Emile Griffith and Benny Paret were facing off at Madison Square Garden for the championship title.

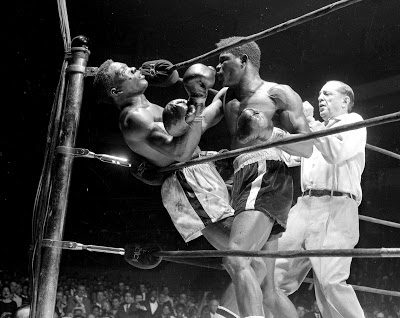

The match proceeded through 12 rounds, in a steady back-and-forth. But then Griffith backed Paret into a corner, unleashing a barrage of punches — 18 in five seconds — to Paret’s stomach and head. Norman Mailer, who was ringside, wrote of the moment that Griffith “made a pent-up whimpering sound all the while he attacked, the right hand whipping like a piston rod which has broken through the crankcase, or like a baseball bat demolishing a pumpkin.”

A referee leapt forward and pulled Griffith away — but it was too late.

Paret had gone slack against the ropes, his white satin shorts blood-spattered. “As he took those eighteen punches something happened to everyone who was in psychic range of the event,” Jonathan Coleman wrote in The New Yorker.

Griffith was declared the winner, but Paret was badly hurt, his unconscious body ferried out of the ring and up the aisle. As Coleman reported, “It might as well have been a funeral procession without a casket.”

For a while, it looked as though Paret was going to pull through. He was rushed into surgery to relieve pressure from two blood clots in his brain, and appeared to show signs of improvement. But ten days later, with his pregnant wife at his side, he was pronounced dead. “Please take me with you,” she wailed.

The story of Paret and Griffith seemed at first a simple tragedy — a life lost to a brutal sport. But an incident that occurred before the match would forever complicate the simple narrative about that night at Madison Square Garden, and Griffith would remain haunted for life.

Rumors about Griffith’s sexuality had been swirling for quite some time in the heteronormative world of boxing. “I hate that kind of guy,” Paret was reported to have said earlier that day, before the fight. “A fighter’s got to look and talk and act like a man.”

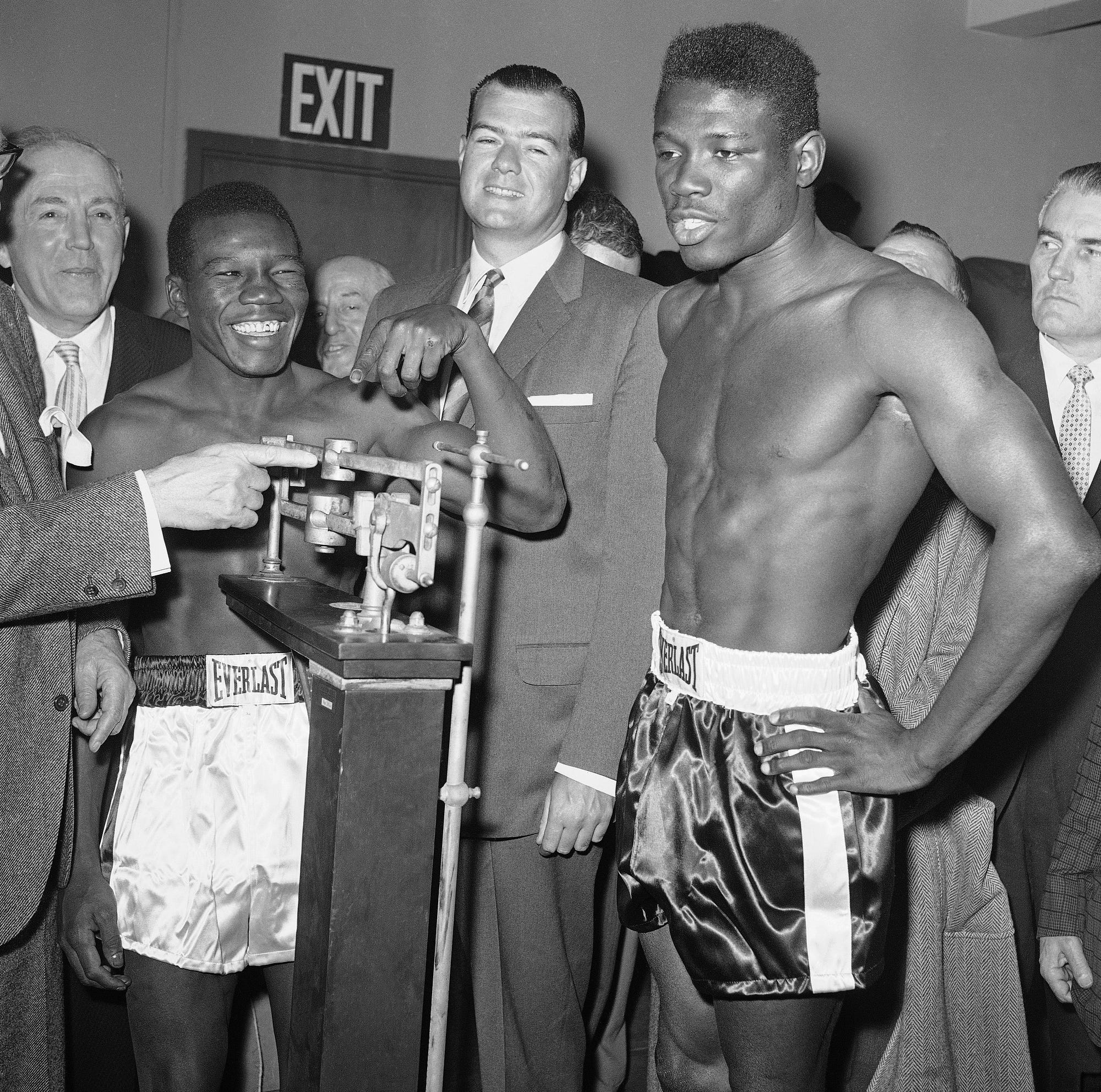

According to historian Troy Rondinone’s book Friday Night Fighter, while Griffith stood on the scales during the weigh-in, wearing nothing but his underwear and socks, Paret came up behind him, grabbed him inappropriately, and used a Spanish slang word that translates roughly to “faggot.” “Hey maricón,” he said. “I’m going to get you and your husband.” As Rondinone explained, “Griffith did have what today we would call a boyfriend. But at the time, he did not consider himself gay, or straight, or anything. He was just Emile.” Paret’s comment was intended as an assault on his opponent’s identity, an attempt to undermine his confidence about his place in a sport defined by machismo. Griffith lunged at Paret, but his trainer held him back, telling him to “save it for tonight.”

Had Griffith’s outrage at Paret’s homophobia intensified his fighting? Or was he just doing what every boxer does: sensing the end of a fight and closing in on the win? Griffith hadn’t meant to kill Paret. In the locker room after the fight, Sports Illustrated quoted him as saying, “I pray to God — I say from my heart — he’s all right.” But the question would dog Griffith for the rest of his career — as would questions of identity in the hypermasculine world of boxing.

Griffith was born into a large family in the Virgin Islands in 1938. When his father left them, his mother went to New York to find work, leaving Griffith and his siblings with relatives. When Griffith was a teenager, his mother sent for him. She had gotten him a job at a hat factory in Manhattan, the owner of which was an amateur boxer and pegged Griffith as having a boxer’s build. Griffith had gone pro by the time he was 20.

Boxing was Griffith’s way out of the factory, but it constrained his sense of self. And never mind the sport being defined by machismo — the world was defined by it. As historian Rondinone points out, there were no openly gay politicians or celebrities at the time, and homosexuality was defined by doctors as an illness. Those who were outed against their will were forced to resign their posts and sometimes arrested on “morality charges,” as was the case two years after the fight, when President Johnson’s closest aide was arrested and forced to retire in the wake of a gay-sex sting. But Griffith’s sexuality was complicated. He had relationships with both men and women, and rumors about him continued to circulate. Yet for the rest of his life, he would refuse to define his sexual identity, either because it defied tidy explanations or for fear of repercussions.

Though Griffith continued to box for 15 years after Paret’s death (and later dabble as a trainer), he was never the same. “After Paret, I never wanted to hurt a guy again,” he told Sports Illustrated in 2005. “I was so scared to hit someone, I was always holding back.” In 1992, as he was leaving a gay bar in Times Square, he was attacked by a group of men and beaten so viciously that he nearly died from kidney damage. He never fully regained his health after the incident, and the attackers were never caught.

He spent the rest of his life refusing to be pigeonholed by the world’s relentless hunger for clear labels. In interviews, he appeared tormented by discussions of his sexuality. “I don’t know what I am,” Griffith told Sports Illustrated. “I love men and women the same, but if you ask me which is better … I like women.”

A New York Times reporter, Bob Herbert, wrote in 2005, “I asked Mr. Griffith if he was gay, and he told me no … But he looked as if he wanted to say more. He told me he had struggled his entire life with his sexuality, and agonized over what he could say about it … But after all these years, he wanted to tell the truth. He’d had relations, he said, with men and women. He no longer wanted to hide. He hoped to ride this year in New York’s Gay Pride Parade.”

After Griffith retired, he met with Paret’s grown son, who had been two years old when his father died. The meeting was amicable. They took a smiling photo together. At the time of his death, in 2013, Griffith was being cared for by his partner, Luis Griffith, whom he had adopted — perhaps as a workaround for the fact that the legal system offered no rights to same-sex partners. Obituaries from the time danced awkwardly around this fact, unsure of how to describe the relationship, which, like all parts of Griffith’s life, defied easy explanations. The New York Times referred to Luis Griffith, in part, as “his longtime companion and caretaker.”

Griffith had lived his life resisting the media’s and his sport’s attempts to define his identity in simple terms. He was, as Rondinone put it best, just Emile.