How America(ns) Failed at Democracy

|

| umair haque 08 Jan. 2018 |

When I go back and forth between Europe and the US, a curious fact always strikes me.

Getting across town in London or Paris or any European capital, on the weekends, can be a chore — because there is almost always some kind of protest happening. Good luck getting across town this Sunday. Now, in my younger days, I used to think: “Dammit! Not again!! I just want to have brunch!” But now, having noticed that the precise opposite is true in New York and Washington and Chicago — protests are the very, very rare exception, that proves the rule that Americans don’t take to the streets — I’m a little more appreciative.

Who’s out protesting? Radical communists? Die-hard adherents of the revolution? Hardly. It’s just everyday people. Students, teachers, doctors, lawyers. They are protesting precisely to keep the rights Americans don’t yet have: to healthcare, education, transport, media, public goods in general. And I think there is a very great truth hidden in all that.

Have Americans failed at being citizens? Now, this is going to be a tough essay to read. My aim, as ever, isn’t merely to condemn or blame or shame America(ns) — but to understand what went wrong with this once thriving democracy, and why.

My little anecdote isn’t just one. US civic engagement rates are abysmally low. However we choose to measure it — turnout, who reads the text of legislation, how many participate in local politics, and so on — these numbers offer imperfect glimpses of a truth we can all feel: somehow, Americans grew disinterested in democracy — as in “citizens actively part of one”. Even as, paradoxically, they grew ever more hypnotized and fascinated by adrenalized 24/7 celebrity politics as a spectator sport. But we will come back to all that.

I often say: for authoritarianism to rise takes the failures of both left and right. But lately I have thought: it takes the failure of the citizenry, too.They must give up on citizenship — as a process, the difficult, challenging, time-consuming process of democracy. In that way, a democracy is only ever really as good as its citizens. And so when I look at America today, I see three tribes, each of whom parallels the three ways that people can abandon the hard work citizenship — with enthusiasm, with reluctance, or through sheer negligence.

The first tribe is the Deconstructionists. These are people like Paul Ryan, and their followers. They don’t believe a government should exist at all — save perhaps as a mechanism to siphon wealth upwards. What role is there then for people to be citizens in the first place? The second tribe is the Apathetics. A little like my friends, or New York Times readers, (my apologies to both), they believe democracy can happen at the tap of a tweet — but genuinely, well, participating in it is something like working the fields: too dirty, messy, and grubby for their delicate, precious hands. The third tribe is the Ignoramuses: cable news watchers, couch potatoes, they genuinely believe that democracy is something that only involves a quadrennial trip to a voting booth.

Now, you will feel that I am being too unkind, and the truth is that I am. For while these three tribes obviously exist, the deeper question is: why have they come to be at all? Why did genuinely participating in democracy (whether by running for office, protesting, meeting, uniting, not just sitting around and yelling at your TV or your Twitter, which is the same thing, really) become something Americans fear and disdain and look down on?Because when you think about it this way, it all makes sense: if a people hold being democracy in contempt in this deep, hidden, pervasive way, then won’t authoritarianism be the natural, inevitable result?

The answer, I think, is something like this: democracy is messy, difficult, hard work. For just that reason, it has become something like a luxury that the average American just can’t afford. He is busy trying desperately somehow to live without savings, retirement, a growing income, stability, security, opportunity — never mind decent healthcare, transport, education, media. How can a person who is starving financially, emotionally, socially, culturally, afford the costs of engaging in democracy? An empty belly comes first. Being a citizen takes time, energy, effort, money — and the average American has been denied precisely all these things, by voracious, monopolistic capitalism.

Americans were taught, made, molded to be consumers, producers, entrepreneurs, investors, owners of a dream about acquisition and possession, first, last, best, and hardest — and citizens dead last. They forgot, in this way, that the former depends on the latter — a nation of fractious citizens can dream, but a people simply daydreaming will not remain free. And in this way, the fire, the passion, the purpose, the spirit, got drained from civic life, democratic engagement, and citizenship.

As capitalism made democracy unaffordable, so too, culture made democracy undesirable. Not so long ago, civic engagement was something that everyone under the age of 35 who was remotely interesting longed to do. But now, somehow, precisely the opposite is true: the only people engaged are the dorks, the extremists, the fringe college Republicans, and so on. What is unattainable can sometimes become cool, ached for, yearned for — but this never somehow happened with democracy in America, precisely because it was never in capitalism’s interest to make democracy something, like a designer handbag, to aspire to.

Instead, a generation was seduced away from it by cable news and spin and talking points — the degeneration of politics into hypercommoditized always-on on-demand spectacle, democracy becoming a reality show. And a generation of young people were taught that only fools and dullards go into government — so who would want to govern for free? Is it any surprise, then, that when capitalism taught them their first obligation was to party, Jersey Shore and so on, hedonism until the sun came up, every college suddenly a gleaming Las Vegas, not exactly a Library of Alexandria — they believed it?

However we look at it, economically, socially, culturally, whichever part of society we look at, old, young, rich, poor, being a citizen — in the fullest sense of the word — became something that was devalued and denigrated, placed at the bottom of people’s priorities, which is precisely what extreme capitalism wanted, and got. What was at the top? Material acquisition, individual aggrandizement, being able to psychically punish your neighbour with your fleeting superiority. In other words, the rewards for civic engagement were negative: “Hey! Aren’t you busy getting rich? Founded that startup already? Finished off your bucket list yet? Dude, why waste your time on, of all things, democracy?”

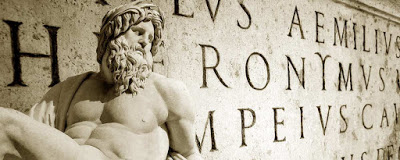

And so, soon enough, within a few generations, just like Romans, Americans stopped being citizens. Today, sure, they carry around passports that say they are citizens. But this is nominal, not substantive. The truth is they act more like subjects, of money, power, and dynasty. They do not have the freedoms the rest of the rich world does — and they do not much appear interested in getting them.

Now, while all that may be true, I’m heartened it becoming less so. Seeing a wave of new faces run for offices that have quite literally never been contested in our lifetimes (LOL, see what I mean by “failing at being citizens”?) is a welcome sign. Perhaps there is some fight left in Americans still, for this noble and beautiful project called democracy.

For in the end, the truth is the old paean that goes something like this: “if you think democracy’s unaffordable, then try the alternative”. And that is where we are now. We are tasting the alternative — authoritarianism, autocracy, tribalism, regression, fealty, feudalism. It tastes bitter and harsh, acrid and sallow. It tastes like decay and rot and putrefaction, like something not fit for human consumption. It tastes like something history wanted us never to have to feast on again. Ruin.