‘Wow, if I close my eyes, it’s like you’re white’

By Sandra Uwiringiyimana, NyTimes, August 22, 2017.

Sandra Uwiringiyimana came to America after fleeing war in Africa. In her

first year of college, she learned tough lessons about being black in America —

starting with a white student who asked if she could touch her skin

Sandra Uwiringiyimana speaks with Women in the

World founder Tina Brown at the San Antonio Salon in November 2016. (Women in

the World)

World founder Tina Brown at the San Antonio Salon in November 2016. (Women in

the World)

Sandra Uwiringiyimana arrived

in America at 12 years old, after a brutal early childhood. Her people had

been forced to

flee their homes in the Democratic Republic of

the Congo because they belonged to a minority tribe. When they made it to a

refugee camp across the border, rebels stormed in with machetes, torches,

and guns. She survived, but many of her friends and family, including her

6-year-old sister, did not. In 2007, she and her surviving family

members came to the U.S. as refugees. Now a college student,

activist, and co-founder of the Jimbere Fund,

which fights poverty in Congo, she describes her journey in her new

memoir, How Dare the Sun Rise,

written with journalist and Women in the World contributor Abigail Pesta. In this excerpt, she recalls her first year at

a college in Houghton, New York, which she later left for another

school, and the tough lessons learned about being black in America.

in America at 12 years old, after a brutal early childhood. Her people had

been forced to

flee their homes in the Democratic Republic of

the Congo because they belonged to a minority tribe. When they made it to a

refugee camp across the border, rebels stormed in with machetes, torches,

and guns. She survived, but many of her friends and family, including her

6-year-old sister, did not. In 2007, she and her surviving family

members came to the U.S. as refugees. Now a college student,

activist, and co-founder of the Jimbere Fund,

which fights poverty in Congo, she describes her journey in her new

memoir, How Dare the Sun Rise,

written with journalist and Women in the World contributor Abigail Pesta. In this excerpt, she recalls her first year at

a college in Houghton, New York, which she later left for another

school, and the tough lessons learned about being black in America.

Eventually, life on campus got

complicated. The majority of students were white, and again there was a racial

divide. I first encountered it with a girl named Angel in my dormitory. She was

white, like most girls in the dorm. I didn’t know her, except to say hello when

we crossed paths on campus.

complicated. The majority of students were white, and again there was a racial

divide. I first encountered it with a girl named Angel in my dormitory. She was

white, like most girls in the dorm. I didn’t know her, except to say hello when

we crossed paths on campus.

One day she was crying in the

hallway. I asked her if she was okay, and she looked at me strangely. She

actually said these words: “Can I touch you?” She said she had never touched a

black person. I humored her, and let her touch me. She closed her eyes and

announced, while stroking my arm, “Wow, if I close my eyes, it’s like

you’re white.”

hallway. I asked her if she was okay, and she looked at me strangely. She

actually said these words: “Can I touch you?” She said she had never touched a

black person. I humored her, and let her touch me. She closed her eyes and

announced, while stroking my arm, “Wow, if I close my eyes, it’s like

you’re white.”

She was astonished that my skin

felt like hers. I laughed and said, “Do not ever try that with any other black

kids. They will not be so amused. They will knock you flat!”

felt like hers. I laughed and said, “Do not ever try that with any other black

kids. They will not be so amused. They will knock you flat!”

Then she wanted to touch my hair,

which was in braids. Again, I said, “Do not try any of these things with other

black kids!” She had come from a tiny rural town with no black people. It would

be the first of many such incidents for me on campus.

which was in braids. Again, I said, “Do not try any of these things with other

black kids!” She had come from a tiny rural town with no black people. It would

be the first of many such incidents for me on campus.

I had been looking forward to

college because I thought I would be meeting a diverse range of people. I was

excited to be independent and to experience life without my parents’ watchful

eyes. I wanted to make new friends, to feel like an average American teen. I

was finally out of high school, so the “no boys until you graduate” rule from

my parents had been lifted. And my brother Alex was not around to shoo

away every boy who coughed in my direction. But I quickly realized that there

was a definite type at Houghton: white skin, long beautiful hair, everything

that I didn’t have. For the most part, white boys liked white girls, and black

boys liked white girls. There was no space for my dark skin. I had male friends

of both races, but I felt more like an accessory to enhance their coolness

factor than a pretty girl they could ask out on a date.

college because I thought I would be meeting a diverse range of people. I was

excited to be independent and to experience life without my parents’ watchful

eyes. I wanted to make new friends, to feel like an average American teen. I

was finally out of high school, so the “no boys until you graduate” rule from

my parents had been lifted. And my brother Alex was not around to shoo

away every boy who coughed in my direction. But I quickly realized that there

was a definite type at Houghton: white skin, long beautiful hair, everything

that I didn’t have. For the most part, white boys liked white girls, and black

boys liked white girls. There was no space for my dark skin. I had male friends

of both races, but I felt more like an accessory to enhance their coolness

factor than a pretty girl they could ask out on a date.

One day I called my mother,

sobbing. She asked me what was wrong, and I had no answer for her. I didn’t

know what was wrong. I thought that if I told her that I didn’t feel beautiful,

she would find it silly and dismiss it. Instead of sharing my feelings, I cried

and told her I missed home.

sobbing. She asked me what was wrong, and I had no answer for her. I didn’t

know what was wrong. I thought that if I told her that I didn’t feel beautiful,

she would find it silly and dismiss it. Instead of sharing my feelings, I cried

and told her I missed home.

One night at a college dance, I

was talking with a cute boy. But then a flirty girl swooped in and pulled him

away. I knew her, and I had thought she was a friend, although I could

see that she was self-absorbed. Her name was Donna, and she thought she

was hot — she thought she was all that and a bag of chips. She whisked the guy

off and started dancing with him, and that was the end of that short-lived

romance for me. It was also the end of my friendship with her.

was talking with a cute boy. But then a flirty girl swooped in and pulled him

away. I knew her, and I had thought she was a friend, although I could

see that she was self-absorbed. Her name was Donna, and she thought she

was hot — she thought she was all that and a bag of chips. She whisked the guy

off and started dancing with him, and that was the end of that short-lived

romance for me. It was also the end of my friendship with her.

Later, I met a white guy who

seemed interested in me — until he said: “Sandra, you’re so pretty for a black

girl.” What? There’s a difference between pretty black girls and pretty white

girls? I wish I had said: “Wow, you’re pretty stupid for a college student.” He

hurt me with his remark. He didn’t see me, just my skin color. But my friends

were there for me. When they heard what he said, they stopped talking to him.

seemed interested in me — until he said: “Sandra, you’re so pretty for a black

girl.” What? There’s a difference between pretty black girls and pretty white

girls? I wish I had said: “Wow, you’re pretty stupid for a college student.” He

hurt me with his remark. He didn’t see me, just my skin color. But my friends

were there for me. When they heard what he said, they stopped talking to him.

I had heard similar comments

about my looks before. I was learning about shades of black in America, and

about how your skin tone determines where you stand on the beauty scale.

Americans are so nutty about physical appearance and what defines beauty.

Basically, the lighter skinned you are, and the smaller and straighter your nose

is, the “prettier” you are.

about my looks before. I was learning about shades of black in America, and

about how your skin tone determines where you stand on the beauty scale.

Americans are so nutty about physical appearance and what defines beauty.

Basically, the lighter skinned you are, and the smaller and straighter your nose

is, the “prettier” you are.

I also began to understand why

hair is such an important issue for African American women. I learned why the

black girls in school didn’t let their hair grow naturally, but instead always

straightened or relaxed it. My black friends explained that since they were

already considered second tier to white women in the looks department, it was

important not to have unruly hair. Black hair, in its natural state, is “nappy”

and disorderly, they told me. They said, “You can’t have your natural hair

out.” They said black women have to keep their hair tidy and straight, like

white women, if they want to be taken seriously at work and in school. Again, I

said, “What? This is crazy.”

hair is such an important issue for African American women. I learned why the

black girls in school didn’t let their hair grow naturally, but instead always

straightened or relaxed it. My black friends explained that since they were

already considered second tier to white women in the looks department, it was

important not to have unruly hair. Black hair, in its natural state, is “nappy”

and disorderly, they told me. They said, “You can’t have your natural hair

out.” They said black women have to keep their hair tidy and straight, like

white women, if they want to be taken seriously at work and in school. Again, I

said, “What? This is crazy.”

These were issues I never had to

deal with in Africa. There, my sisters and I wore our hair short and never gave

it a second thought. We didn’t have to worry about natural hair versus

straightened hair; we didn’t worry about our hair at all. But in America, it

was a very big issue. And so, in order to fit in, as all teens want to do,

I usually wore my hair in braids or straightened it with chemicals, sometimes

burning my scalp if I left the chemicals on for too long.

deal with in Africa. There, my sisters and I wore our hair short and never gave

it a second thought. We didn’t have to worry about natural hair versus

straightened hair; we didn’t worry about our hair at all. But in America, it

was a very big issue. And so, in order to fit in, as all teens want to do,

I usually wore my hair in braids or straightened it with chemicals, sometimes

burning my scalp if I left the chemicals on for too long.

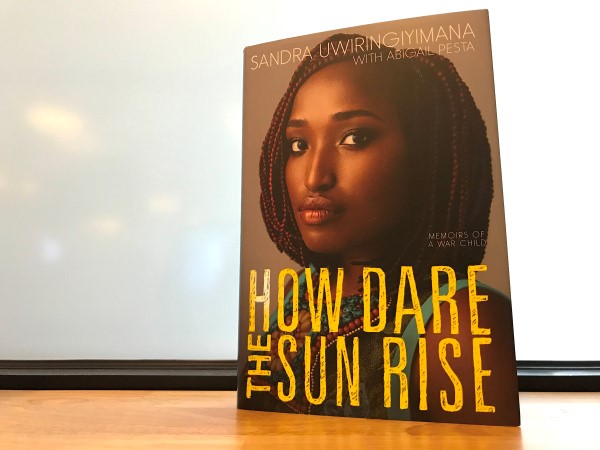

Uwiringiyimana’s new memoir,

written with Abigail Pesta, ‘How Dare The Sun Rise.’

written with Abigail Pesta, ‘How Dare The Sun Rise.’

I didn’t understand how the hair

that grew out of my head could be considered messy. I occasionally wore my hair

out in its natural state, big and puffy. I’ve come to love my hair, but at the

time, when I wore it as an Afro, it sparked a lot of unwanted conversation.

People thought I was making a statement, when I was simply wearing my natural

hair. They would examine it and say things like:

that grew out of my head could be considered messy. I occasionally wore my hair

out in its natural state, big and puffy. I’ve come to love my hair, but at the

time, when I wore it as an Afro, it sparked a lot of unwanted conversation.

People thought I was making a statement, when I was simply wearing my natural

hair. They would examine it and say things like:

“Do you tease your hair?”

“Ooh, your hair is so cool — can

I touch it?”

I touch it?”

“Oh wow, how do you get your hair

to do that?”

to do that?”

White girls would sink their

hands in my Afro and smile as if they were petting me. Not only did they make

me feel like an exotic animal, but they also messed up my hair. How would they

feel if I ran my fingers through their hair?

hands in my Afro and smile as if they were petting me. Not only did they make

me feel like an exotic animal, but they also messed up my hair. How would they

feel if I ran my fingers through their hair?

It was easiest to wear braids. I

didn’t have the time or money to spend hours straightening my hair before

class. Braids are easy to maintain, but they do hurt like mad for a few days

until they settle. The first night after you have them done, you have to find a

creative way to sleep, such as on your forehead. Of course, people thought I

was making a statement by wearing braids too. They thought everything about my

appearance was a statement, when I was simply wearing clothes, going to class,

doing my daily routine. I really stuck out at Houghton. If I wore one of my

African skirts or dresses, people would look me up and down and say things

like:

didn’t have the time or money to spend hours straightening my hair before

class. Braids are easy to maintain, but they do hurt like mad for a few days

until they settle. The first night after you have them done, you have to find a

creative way to sleep, such as on your forehead. Of course, people thought I

was making a statement by wearing braids too. They thought everything about my

appearance was a statement, when I was simply wearing clothes, going to class,

doing my daily routine. I really stuck out at Houghton. If I wore one of my

African skirts or dresses, people would look me up and down and say things

like:

“Oh wow, what’s the occasion?”

“You look like an African

goddess.”

goddess.”

I wanted to say, “Come on now,

it’s just a skirt. It’s not revolutionary.” I know that people meant well. I

tried to laugh it off. Sometimes I just said, “Yeah, I’m an African

goddess.”

it’s just a skirt. It’s not revolutionary.” I know that people meant well. I

tried to laugh it off. Sometimes I just said, “Yeah, I’m an African

goddess.”

To help us all understand one

another, I became president of the Black History Club on campus. We decided to

do a photo exhibit with some of the black students to help people get to know

us a little better. We took portraits and did brief write-ups for everyone —

little introductions with a few details about our lives and interests. We

called the exhibit “Shades of Black.” When the exhibit opened, an idiot student

decided it would be hilarious to change the sign to “50 Shades of Light Black”

and drape paper chains all over the walls — a nod to the book Fifty Shades

of Grey. But when the black students came in and saw the chains, as you can

imagine, they felt incredibly insulted. We were trying to honor black students,

and someone had filled the room with symbols of slavery. The kids started

crying.

another, I became president of the Black History Club on campus. We decided to

do a photo exhibit with some of the black students to help people get to know

us a little better. We took portraits and did brief write-ups for everyone —

little introductions with a few details about our lives and interests. We

called the exhibit “Shades of Black.” When the exhibit opened, an idiot student

decided it would be hilarious to change the sign to “50 Shades of Light Black”

and drape paper chains all over the walls — a nod to the book Fifty Shades

of Grey. But when the black students came in and saw the chains, as you can

imagine, they felt incredibly insulted. We were trying to honor black students,

and someone had filled the room with symbols of slavery. The kids started

crying.

I went to the dean. He knew me by

now. I had spoken with him before about inappropriate comments on campus and

ways to make minorities feel more at home. When I arrived at his office, I

could see from the look on his face that he was thinking, Uh-oh, what now? I

told him about the chains strung across the portraits. I explained that this

was devastating for the black students on campus. I said, “What are we going to

do about this?” To add to the urgency, I said we needed to do something before

everyone started tweeting about it. School officials promptly looked at the

campus security cameras and figured out who did it, although they didn’t

release the student’s name immediately.

now. I had spoken with him before about inappropriate comments on campus and

ways to make minorities feel more at home. When I arrived at his office, I

could see from the look on his face that he was thinking, Uh-oh, what now? I

told him about the chains strung across the portraits. I explained that this

was devastating for the black students on campus. I said, “What are we going to

do about this?” To add to the urgency, I said we needed to do something before

everyone started tweeting about it. School officials promptly looked at the

campus security cameras and figured out who did it, although they didn’t

release the student’s name immediately.

It was a white boy. He had to

apologize and he got suspended, but that didn’t feel like enough. This student

did something that he thought his peers were going to find funny. This was a

small manifestation of a much larger issue on campus. These kinds of antics

were not what I expected from my college experience.

apologize and he got suspended, but that didn’t feel like enough. This student

did something that he thought his peers were going to find funny. This was a

small manifestation of a much larger issue on campus. These kinds of antics

were not what I expected from my college experience.

Excerpted from How Dare the Sun Rise,

by Sandra Uwiringiyimana with Abigail Pesta, published by Katherine Tegen

Books, an imprint of HarperCollins.

by Sandra Uwiringiyimana with Abigail Pesta, published by Katherine Tegen

Books, an imprint of HarperCollins.