Terror at the Factory Gate: The Price of Making Cement in Syria

September 28, 2016

For three chaotic years starting in 2011, as Syria imploded into civil war, Lafarge SA of France kept churning out cement from its factory in the northern desert near the Turkish border.

To keep production going and safeguard the $680 million installation, according to the site’s former security manager, Jacob Waerness, the company had to resort to extreme measures including negotiating freedom for kidnapped employees and cutting supply deals with local fighters, whose allegiances shifted with the sands.

Jacob Waerness Source: Jacob Waerness

Lafarge, which has since merged with Swiss rival Holcim Ltd. to become the world’s biggest cement maker, had invested in the Syrian plant in a bet that expansion in the then relatively-stable Middle Eastern country would turn a tidy profit.

Instead, like countless other multinationals with sprawling operations in far-flung regions, the French company learned the hard way that political tides can turn suddenly and violently. But unlike most companies caught in turmoil, whose actions don’t become public, Lafarge’s predicament in the war-torn country is now under the spotlight. In a 245-page book published last month in his native Norwegian, Waerness offers a rare insider view of corporate decision-making during times of strife.

“We didn’t do this to profit from a war situation,” he said in an interview. “We wanted to keep the factory running to avoid having it destroyed.”

Plant Seized

Lafarge may have misjudged the situation, according to the former manager, hanging on for too long in Syria until militant group Islamic State was literally outside the factory gates. The plant was seized by the group in September 2014. Waerness left the year before when his local contract expired and stopped working for Lafarge in Zurich in March this year.

In the early days of political turmoil, when other companies were pulling out of Syria, Waerness said Lafarge decided the best way to protect its factory and help the local community would be to try to ride out the storm. That decision has now earned the cement maker media attention as well as scrutiny from French lawmakers about whether it engaged with IS during the conflict.

“We said that if it came down to human lives we would shut down, but as long as it was only about hard work and adapting to a difficult situation, we would do everything to run the business in what we felt was a responsible way,” Waerness said. “That proved increasingly difficult.”

Islamic Extremists

To keep production going in Syria even as nearby cities fell to Islamic extremists, Lafarge went to such lengths as equipping trucks with armor for safer transport, smuggling a Filipino welder across the Turkish border to help with maintenance and indirectly helping groups like IS, according to the ex-manager, who said he accepts at least part of the blame for the company staying so long.

“When we realized that they were there to stay, we should have pulled out,” Waerness said. “We couldn’t operate in the region without those groups directly or indirectly benefiting from our operations.”

In response to questions about the book, Lafarge said that any benefit to IS “would be completely contradictory” to the company’s values and code of conduct, and that its first priority when the conflict reached the area of the plant was the safety and security of the employees. It’s carrying out an internal investigation into what happened in Syria during the period when the plant was surrounded by armed factions.

“This review is still ongoing and, at this stage, we have not made conclusions of any wrongdoing,” the company said. “We will include the assertions made in Mr. Waerness’s book in our review and we will also invite him to contribute to the review.”

French Lawmakers

A French parliamentary report published in July concluded that lawmakers didn’t have evidence that Lafarge or its local entities contributed — directly, indirectly or passively — to the financing of IS. French newspaper Le Monde, which reported in June about payments to IS to keep the plant working in 2013 and 2014, said the funding was indirect and management may not have even been aware.

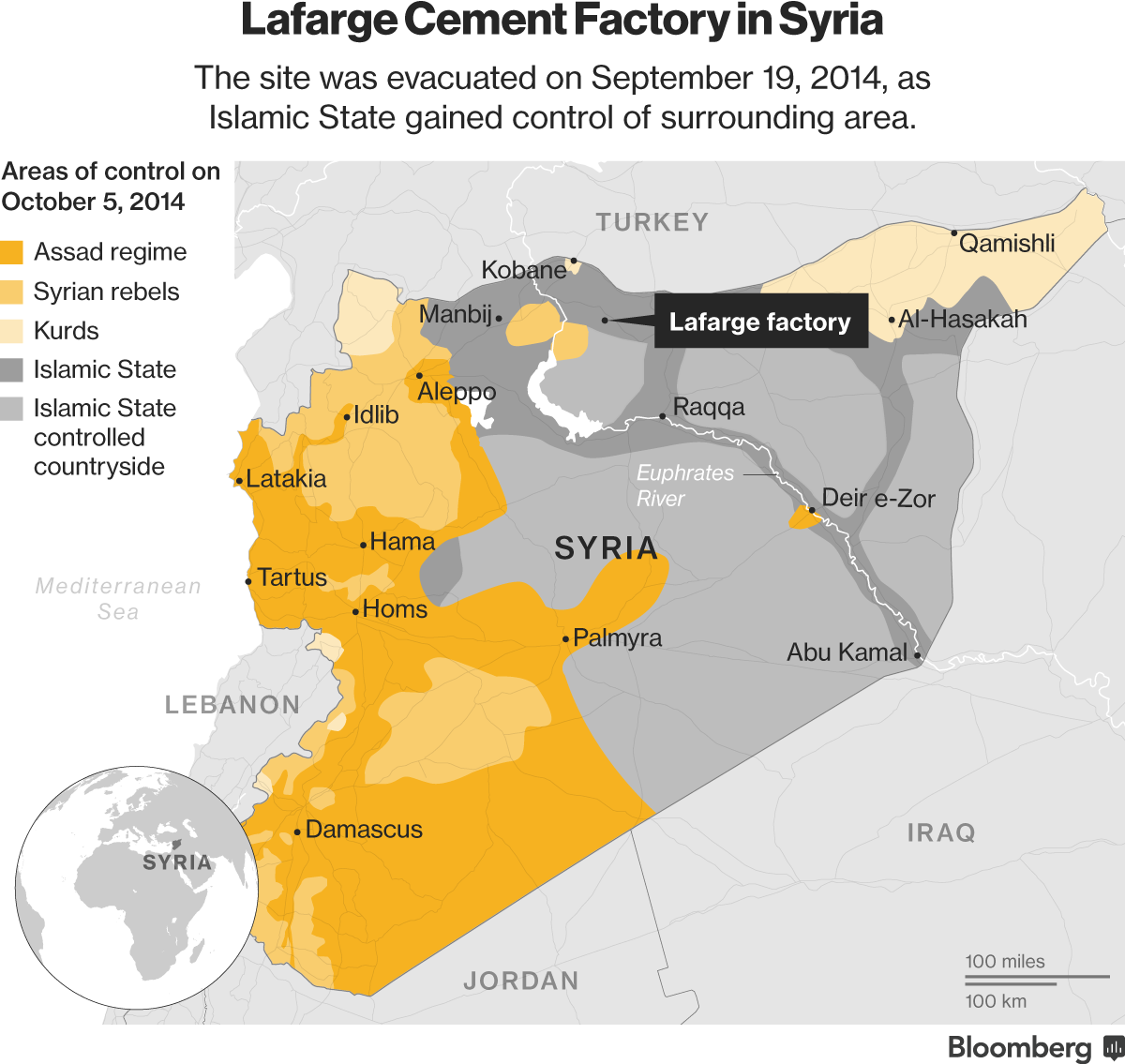

Lafarge’s Jalabiyeh factory had only been operational for about six months when protests against the Syrian regime erupted in March 2011. Located east of Aleppo, about 87 kilometers northwest of Raqqa, which would become the capital of IS, the area was at first mostly peaceful, Waerness said.

Red Lines

Producing thousands of tons of cement daily and employing about 200 people, it was an important contributor to the local economy and the Kurdish-majority population in the area wanted production to continue, he said.

In the early days, Lafarge set out a number of “red lines” — such as the occupation by a militant group of the surrounding area — as situations that would require a pull out from the site. As civil war intensified, crossing the lines went from being exceptional to routine, he said.

The militants who gained local control when government forces withdrew were in favor of continued production, according to Waerness. Later more extreme groups increased their influence in the area until, he said, he was offered and declined a meeting with the IS finance chief in Raqqa in the summer of 2013.

After Waerness left Syria, Lafarge continued to operate the cement factory for another full year, and the final evacuation from the factory took place on Sept. 19, 2014. Days later, IS fighters took control. Lafarge has since written it off. This week, the 5 1/2-year war escalated with intense bombing in Aleppo that led to an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council.

“You operate in a constant state of emergency,” Waerness said. “The road is formed as you’re walking it, and it’s not until afterward that you can reflect and see that we did a lot of good things, but in some areas we went wrong.”