The Convergence of Conflict and Crime: Impact on Preventive Diplomacy and Peacemaking

August 12, 2016

Poppy eradication campaign in north-eastern Afghan province of Badakhshan. Photo: UNAMA

Recent experiences in Mali, the Sahel, and North Africa all bear witness to the impact of shifting alliances between different state forces, rebel groups, and criminal networks, while a growing body of evidence suggests that today’s armed conflicts generate organized crime. These are some of the observations of a new DPA-commissioned paper on the impact of organized crime on conflict prevention, peacemaking and peacebuilding and how the UN can better face up to it.

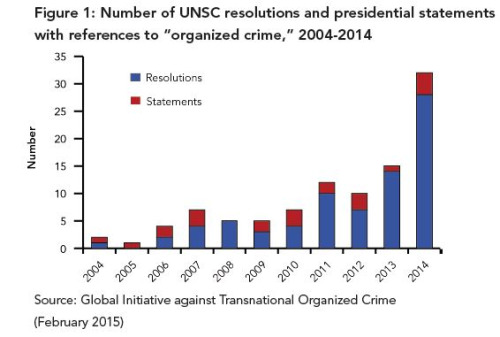

The paper – Crime-Proofing Conflict Prevention, Management, and Peacebuilding: A Review of Emerging Good Practice – notes that peace operations take place today in highly complex and fluid strategic environments, where groups with clear criminal agendas have a major impact on conflict dynamics, peace processes, and post-war transitions. While traditional conflict analysis has tended to treat criminal and political actors as entirely separate (the “upperworld” versus the “underworld”), emerging research and evidence from a variety of settings suggest that this hard and fast distinction is overstated. The increasing international recognition of the close connections between organized crime and conflict in recent years is borne out by one important measure, namely the number of Security Council resolutions and statements with references to such crime adopted since 2004, as illustrated in the figure below.

Recognizing that organized crime is not always separated from, but is in fact sometimes intertwined with, politics has potentially serious implications for the work of DPA and other entities working in conflict prevention, peacemaking and peacebuilding. Where criminal agendas are present, conflict-related work requires “crime-proofing”, or putting the focus not just on formal politics but also on informal and illicit political economy.

According to the paper, “crime-proofing” requires that DPA and others boost analytical capacities for mapping criminal networks and illicit economies, including through the development of risk indicators at both local and transnational levels that can effectively feed into the planning and design of political missions.

The paper also recommends that, to limit the influence of organized crime in transitional political arrangements, DPA should consider crime-proofing its electoral assistance practices and strengthening its anti-corruption programming, particularly at the local level. And it calls on DPA to, at minimum, act to prevent the unintended facilitation of organized crime as a consequence of UN interventions. It can do this in promoting the development of guidance on how to identify and understand what drives criminal actors; in encouraging sensitivity in UN procurement practices to impacts on informal and illicit economies; in limiting opportunities for the criminal infiltration of UN police reform and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs; and, especially, in the design, implementation, and review of sanctions regimes.

For Eugenia Zorbas, of DPA’s policy planning team, “the convergence between armed groups and organized crime, and the hybridization of their strategies, is evident, even if it is very difficult to gather reliable data on organized crime – perhaps even more so when it comes to interaction with government officials.”

“This research paper points us to some possible ‘good practices’ based on a review of how other organizations, external to the UN, have begun to tackle different aspects of this problem,” she added.