Ukraine: the fate of displaced persons

di Matteo Tacconi, June 01 2016.

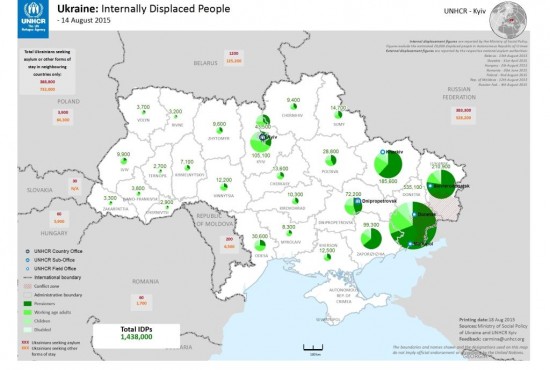

War in the Ukraine has caused about

1,5 million internally displaced persons.

The living conditions of

those who have fled the war zone in the east of the country are often

very difficult.

(This text is published as a

collaboration between OBC and Eurozine, part of the Eurozine-project

‘Beyond

conflict stories: Revealing public debate in Ukraine’ supported

by a grant from the Open Society Initiative in Europe within the Open

Society Foundations)

When military planes flashed through

the spring sky of Luhansk three years ago, and shots were heard in

some areas of the city, Elena Dyurugyna, 34, knew that things would

only get worse. She was right. Luhansk, Donetsk and the insurgent

areas in eastern Ukraine would shortly become the theatre of a war

between government forces and pro-Russian rebels.

At the time, Elena’s daughter was

two years old.

“I thought she should not see the war. I had work to

finish.

As soon as I was done I went to Kiev. I had no other choice.

I had studied in the capital for two years, so I knew it and liked

it. My husband had to stay in Luhansk during the worst of the

fighting because of his work. Then, in September of 2014, he joined

us”.

Elena is a photographer, and when she

left Luhansk she sold her camera and her equipment. She needed money

for the travel, to pay the rent and to feed her daughter.

At the

beginning, in Kiev, she worked in a MacDonald’s. She didn’t think

she would return to her old job, at least not soon.

However, she did

go back to taking photos. She specialised in photos of children, and

has kindergartens and schools among her clients. She takes portraits

and she does weddings.

Her studio is on the eleventh floor of a

building near the Livoberezhna underground station.

It is the same

address as the head office of the NGO, Krymskaya Diaspora, that

originally started to help those fleeing Crimea, the southern

peninsula annexed to Russia in March of 2014. They quickly widened

their action to help displaced persons from the crisis in Donbass,

which followed closely on that of Crimea.

NGOs

and Internally Displaced Persons

While attending a business course at

Krymskaya Diaspora, Elena Dyurugyna was given the money necessary to

buy back a camera and the necessary equipment.

Krymskaya Diaspora

made a studio available to her.

“The course was useful. It taught

me how to plan, to develop a strategy and how to promote myself. It

was also very competitive. We were two hundred and only seventeen of

us received funds”.

Krymskaya Diaspora is only one of the

NGOs, almost all of which are organised by volunteers and obliged to

work with donations, helping in Kiev and in the rest of the country

those internationally known as Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs).

That is, those who have left their homes and moved to other cities

and places in Ukraine because of the conflict. According to the

latest data relating to August 2015 from the UN High Commissioner for

Refugees (UNHCR), the number of IDPs in Ukraine is around 1,5

million.

Another one million have gone to Russia, according to the

authorities in Moscow.

Even the choice of where to go is

politically motivated.

This could not be otherwise in a country which

has been brutally divided since the Maidan uprising. Those who cross

the border feel an empathy for Russia, and do not trust the

government in Kiev. “Those who leave the area under the control of

the latter, make an informed choice for Ukraine, whereas crossing

into Russia would be easier”, says Lesia Lytvynova, co-founder of

Frolivska 9/11, another NGO helping displaced persons.

Their life is not easy. “About two

years ago, the government passed a law to protect their social rights

and to initially allow them a financial contribution”, states Olga

Semenova, from the Job Centre for free people, another NGO helping

the IDPs. “However, this is bound by technical and bureaucratic

steps which, in reality, make it difficult to function. These people

are asked to produce documentation, which mostly they do not have.

Therefore, our task is to defend their rights to health services, to

work, to kindergarten and to study”.

Resettlement

in Kiev

Employment is the main theme of the

organisation for which Olga Semenova works, as indicated by the name.

“Of the more than 15,000 people who contacted our NGO in our first

two years of activity, a third have found work. We have 3,000

companies listed in our database. We have also organised professional

courses for 5,500 people and allowed fifty startups to get going”.

To act as a bridge between displaced

people and companies is in itself hard work. Even more so in a

situation such as this, marked by a deep depression. In 2015, the

country lost 9,9 GDP points. Also “many of the displaced persons

are miserable, frustrated. Out of ten who turn to us, an average of

only three are motivated”, Natalia tells us.

She works at the Job

Centre for free people answering the calls coming in on the specially

created number.

Frustration feeds on the scarcity of

work opportunities, and on a sense of disorientation, having had to

leave one’s own land. Resettlement in Kiev is not always easy.

“At

the beginning, local people were supportive towards these people

arriving without anything. They were willing to give, sometimes even

to give hospitality. But as time passed things gradually changed. The

state did not take all the responsibility it should have taken. The

management of the displaced persons fell on the local communities”,

says Lesia Lytvynova.

The Frolivska 9/11 storeroom is

connected to the road by a window. Anyone who wants can leave food,

clothing and toys. A couple in their sixties passes. They have a sack

with them from which they take out something for the refugees. They

still give.

SOURCE: Balcanicaucaso